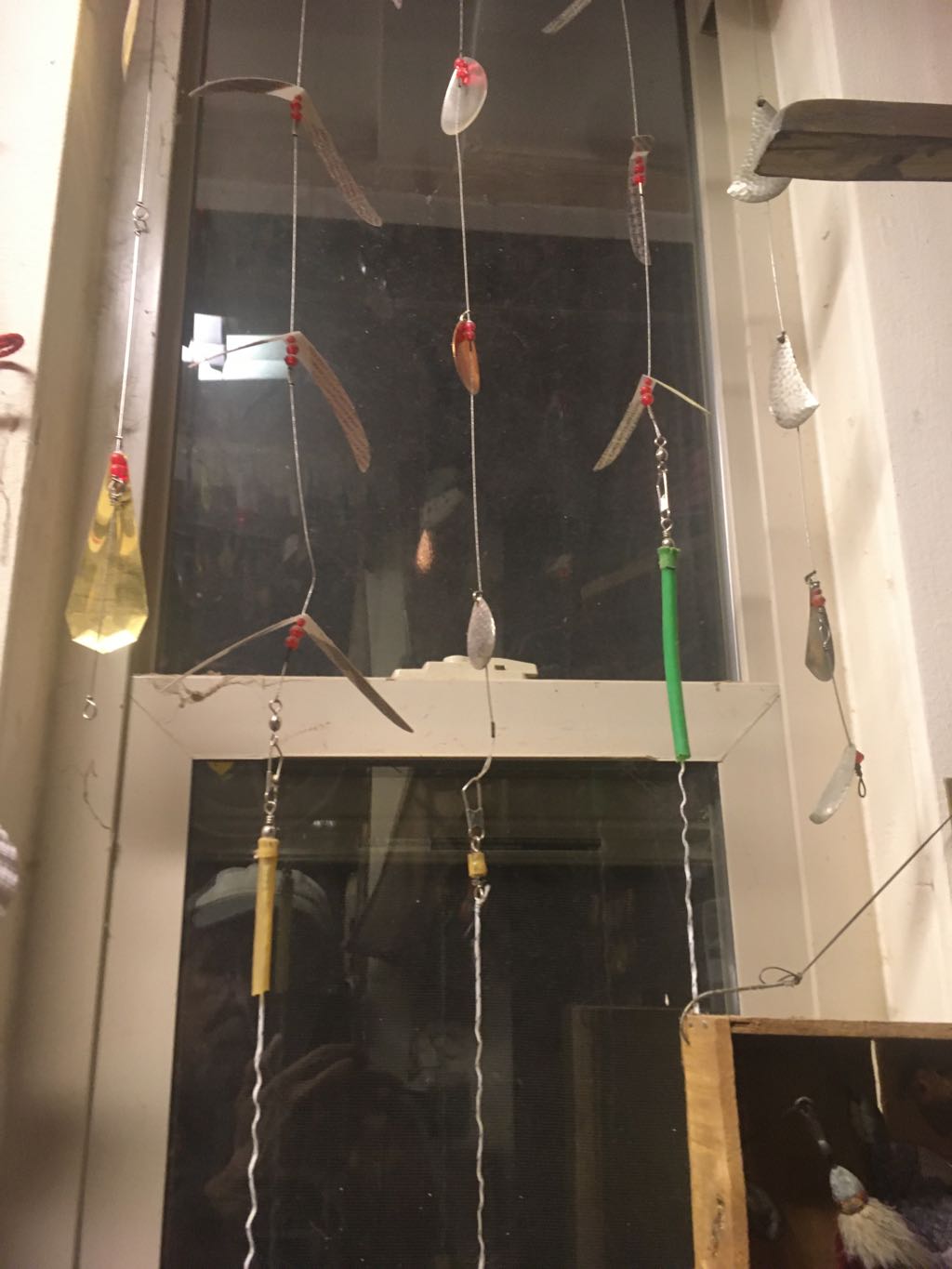

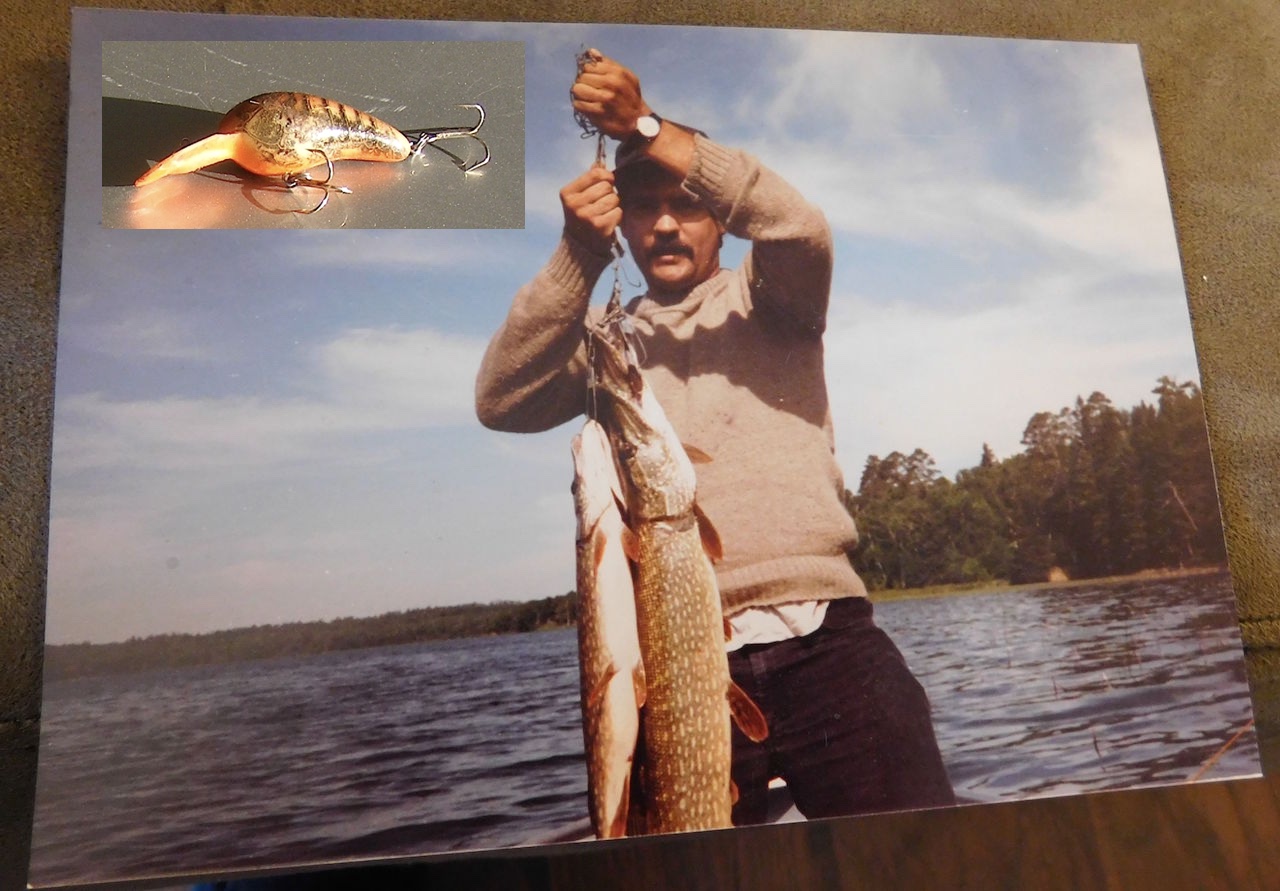

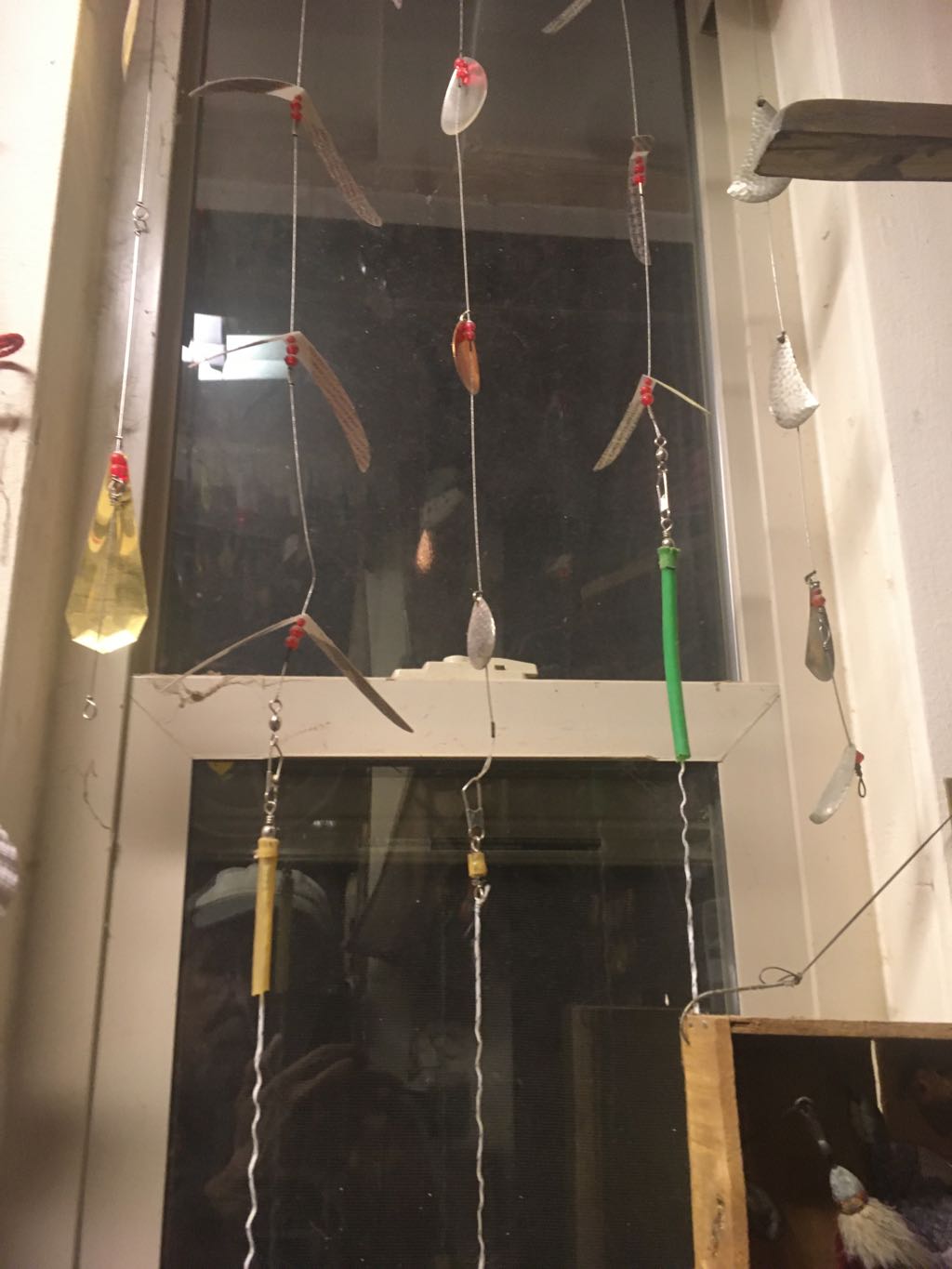

fishinglures.jpg

LEFT: My dingbat that I caught big bass on. MIDDLE:

Jeff's jig that he lost underwater in the crappie

hole and which later I dove down and saw and

recovered. RIGHT: Bill Underhill's super beetle.

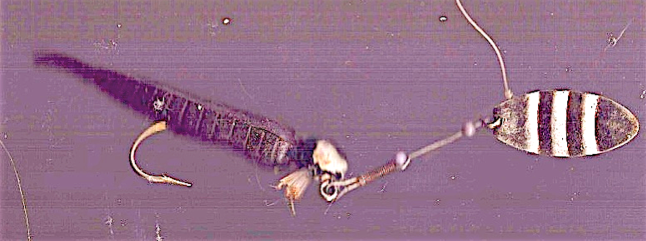

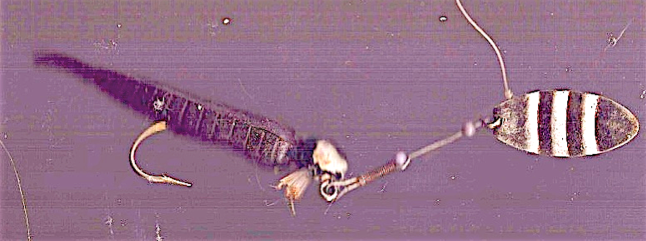

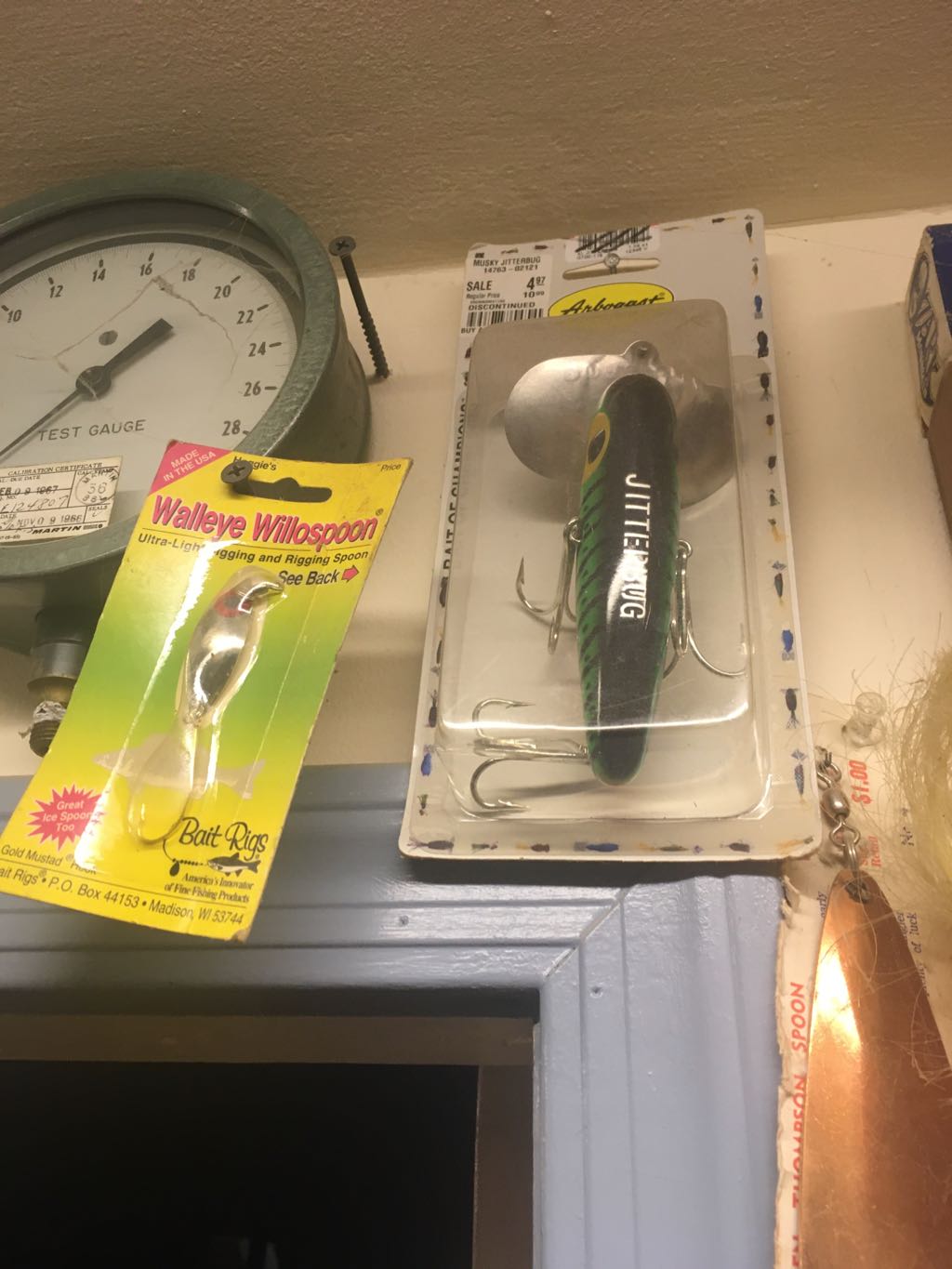

jigfly picture.jpg

The Canadian Jigfly above is the first lure I ever

caught a fish on.

The jaws of that very fish are in the picture too!

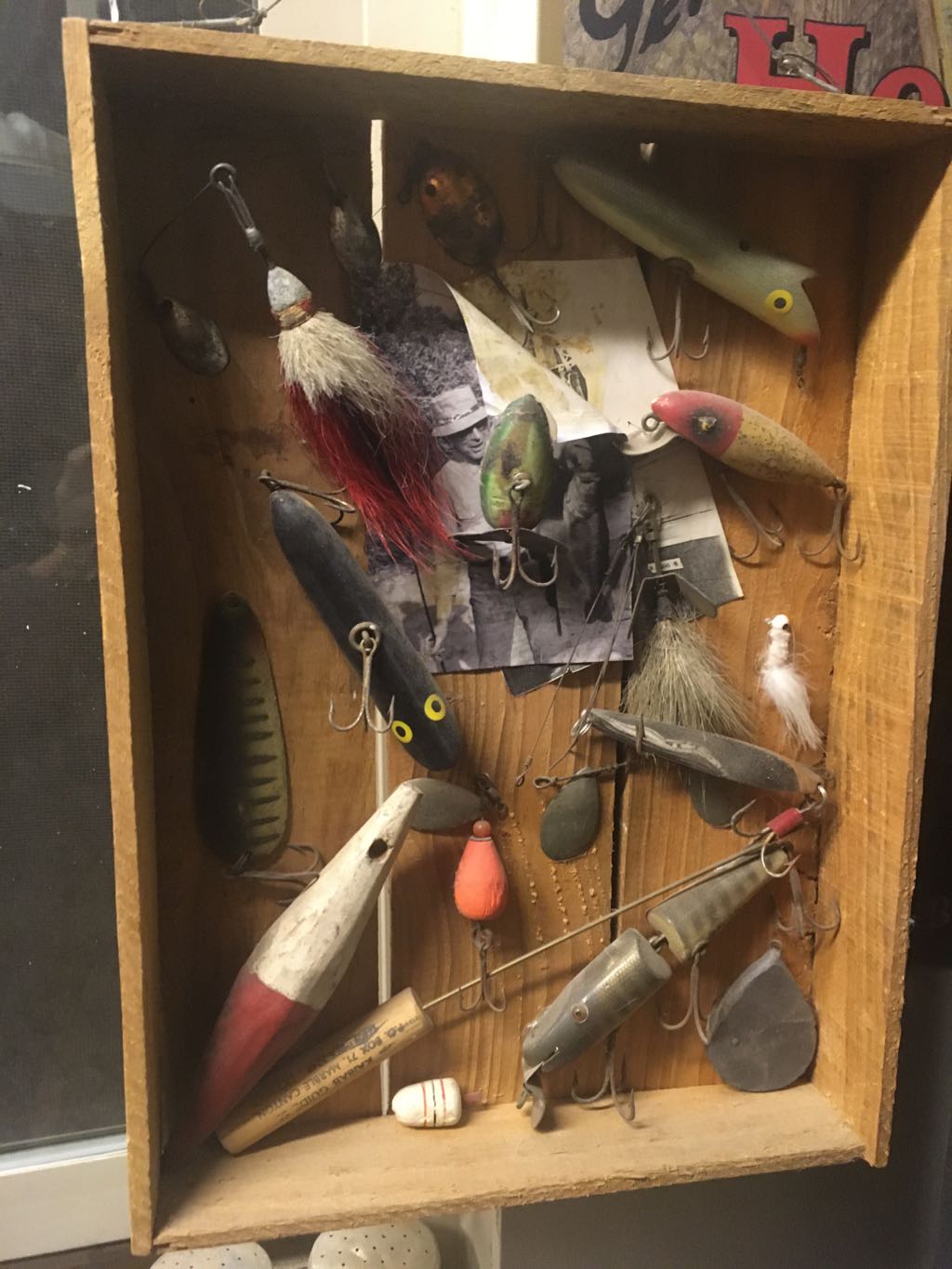

retired fishing lures1.jpg

First Bird NotebookIMG_5856.JPG

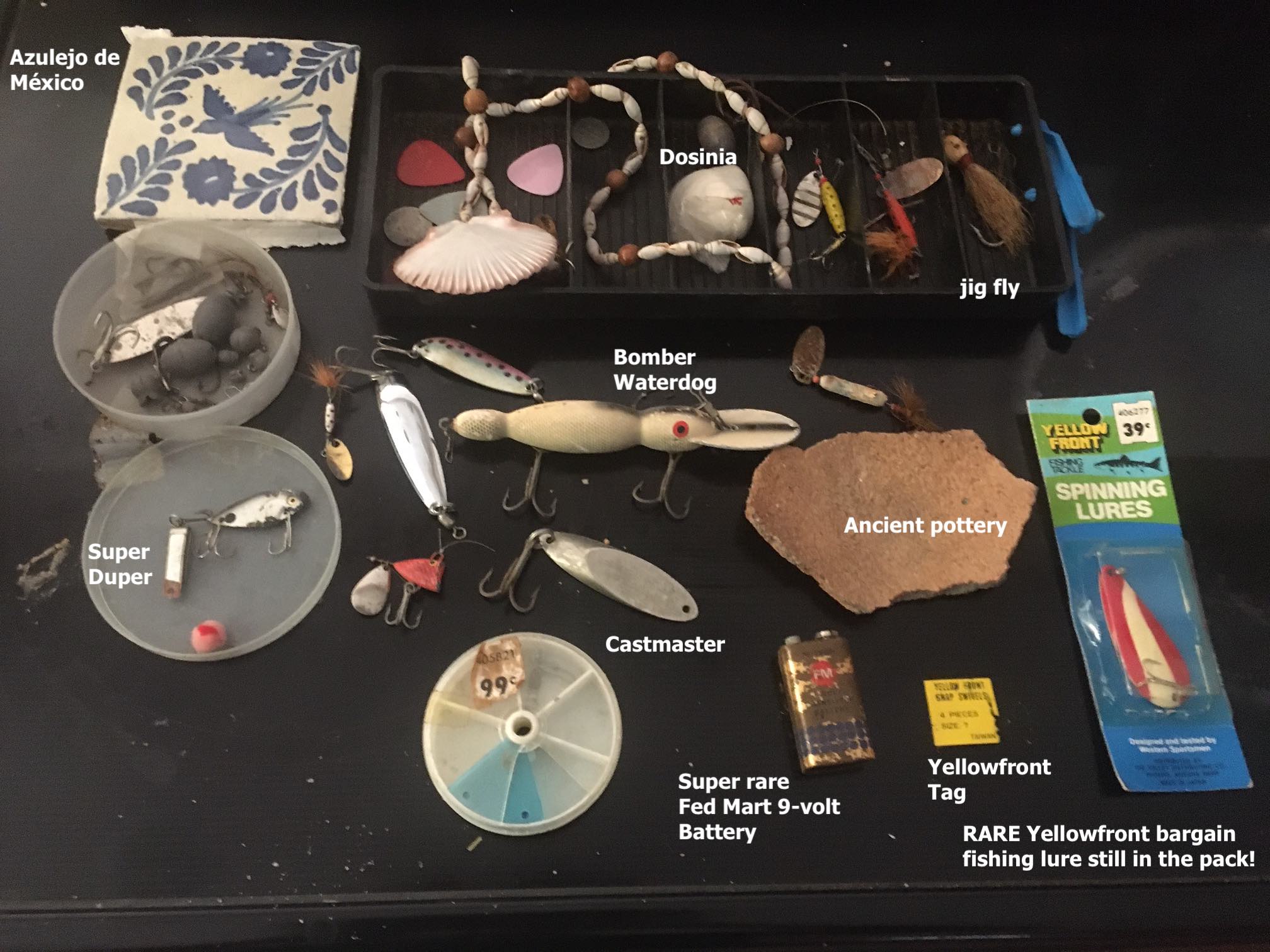

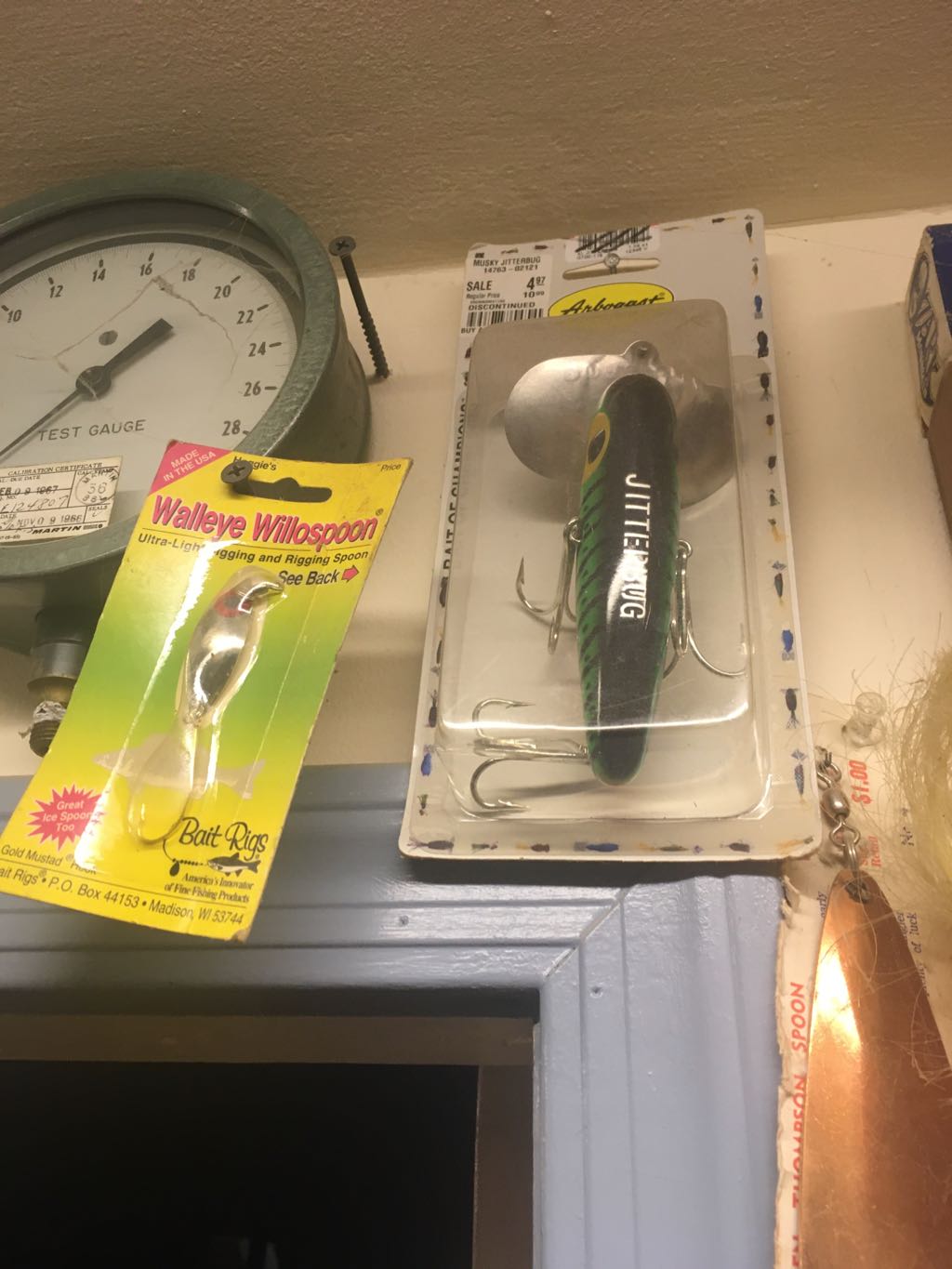

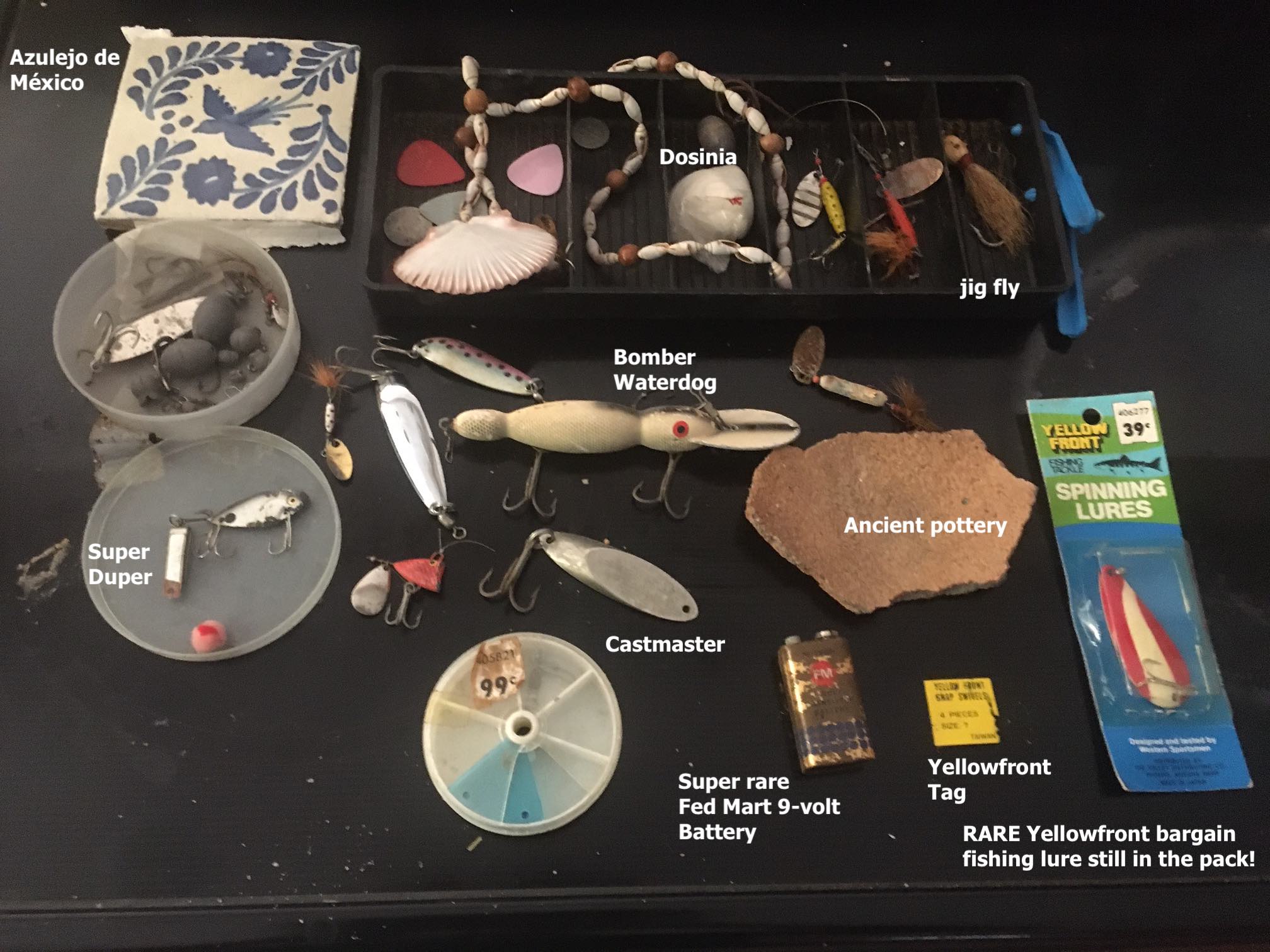

Yellow Front Red and White Spoon

Fishing Lure Still in Its

Packaging.jpg

Took it home from Mexico in Nov of 2019

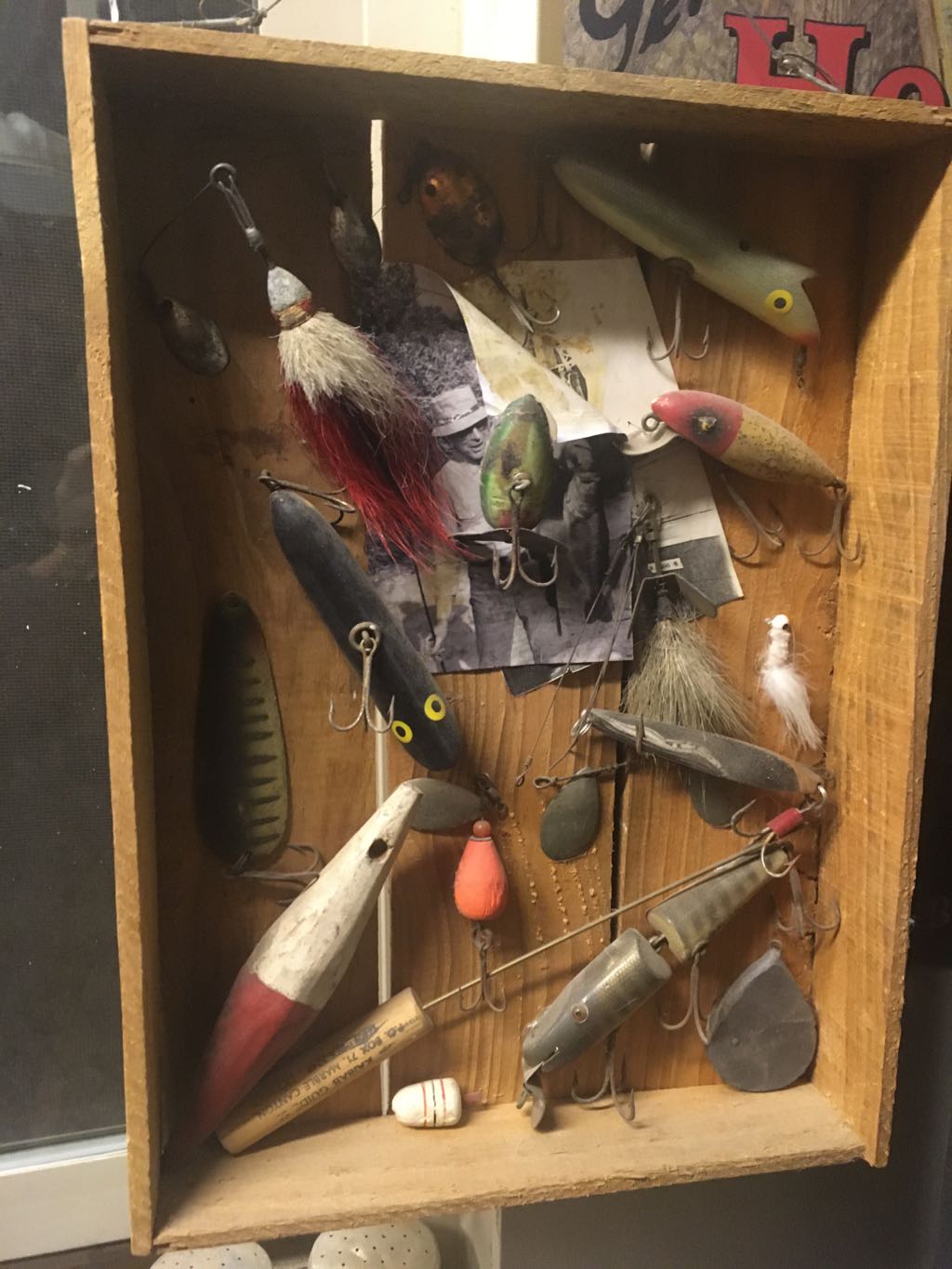

retired fishing lures2.jpg

MIDDLE:

Perch-colored Lazy Ike, a walleye killer!

RIGHT AND BELOW THE LAZY IKE:

Steve's Yellow Jitterbug. Destroyer of

bass!

TOP RIGHT:

The Deep-divin' Jesus, the lure Steve

tricked a Jesus freak into giving him

free. We caught these

fish with it.

SMALL GREEN RUBBER POPPER:

Steve's popper from first trip to Itasca.

OTHER LURES: jointed Mirror

Lure, White Creek Chub Lure, spotted super

sonic-like lure. Bottom left: large-sized

Lazy Ike.

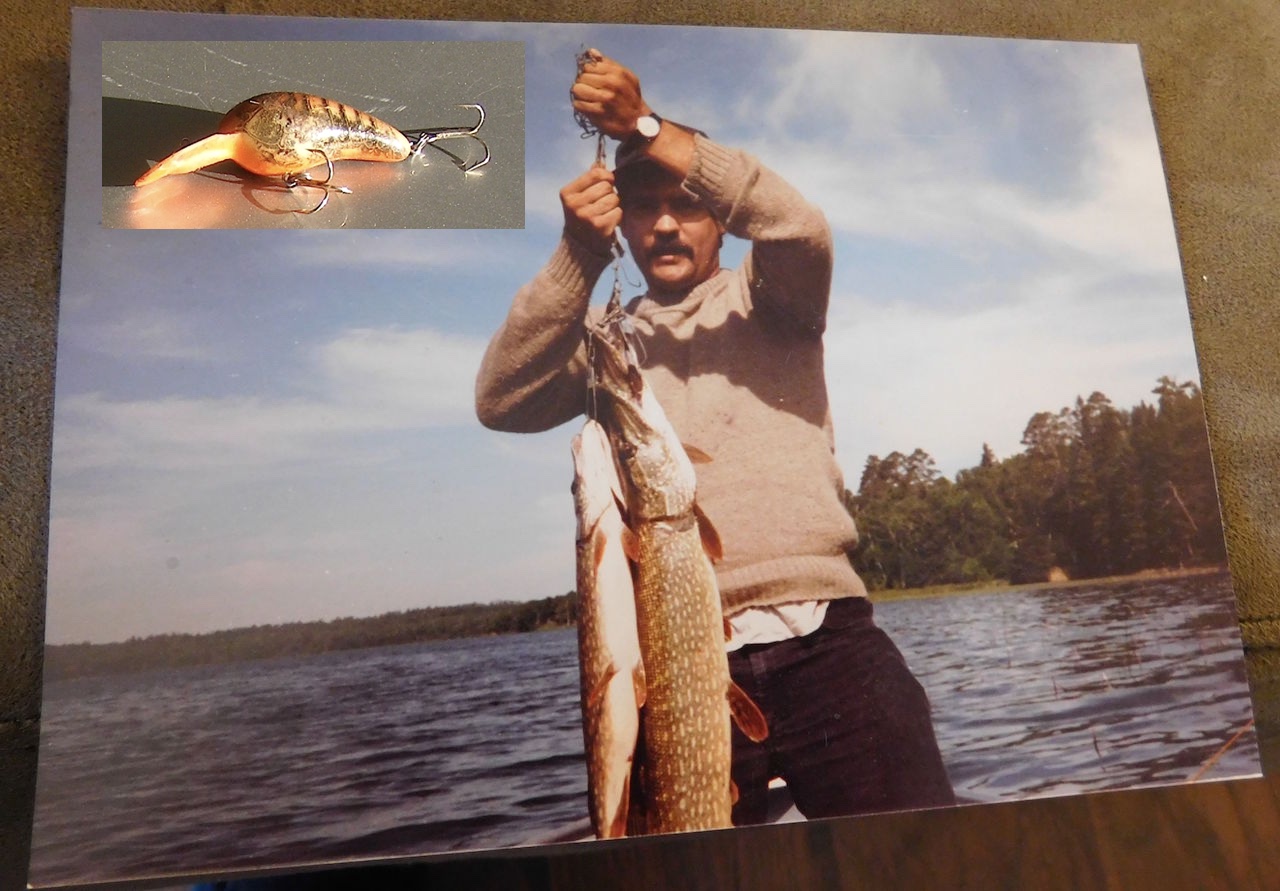

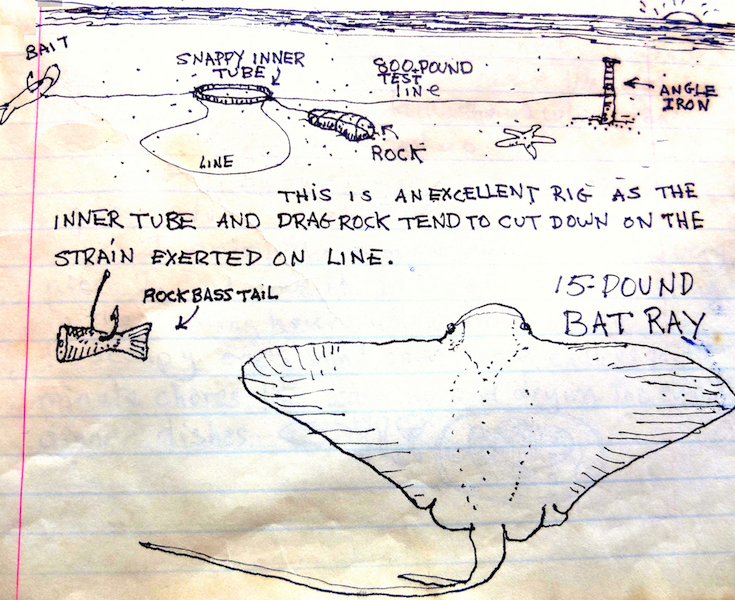

Tom, Pike, Itasca 1987, Deep Diving

Jesus.png

fishinglures2.jpg

TOP:

My Meadow Mouse, which I never

caught a fish on and whose tail

is missing.

LEFT MIDDLE: The lazy ike-like

lure that Bill Underhill gave

me. It is a rattler.

Assorted poppers that are spread

about; some are obviously

homemade.

MIDDLE: Red-headed Basareeno.

It's the ORIGINAL folks.

RIGHT: Giant sized Lazy Ike. I

remember losing a bass on it out

by the bog across the lake near

Schoolcraft Island.

Popping Bug

Close-up.jpg

Sonny with Bass he caught on my jitterbug Douglas

Lodge Itasca year 2000.jpg

caliopespoonjeff.jpg

And Jeff's jasper-like rock from the East Verde?

It's Jeff's anyhow.

Bill Underhill's Super Beetle.png

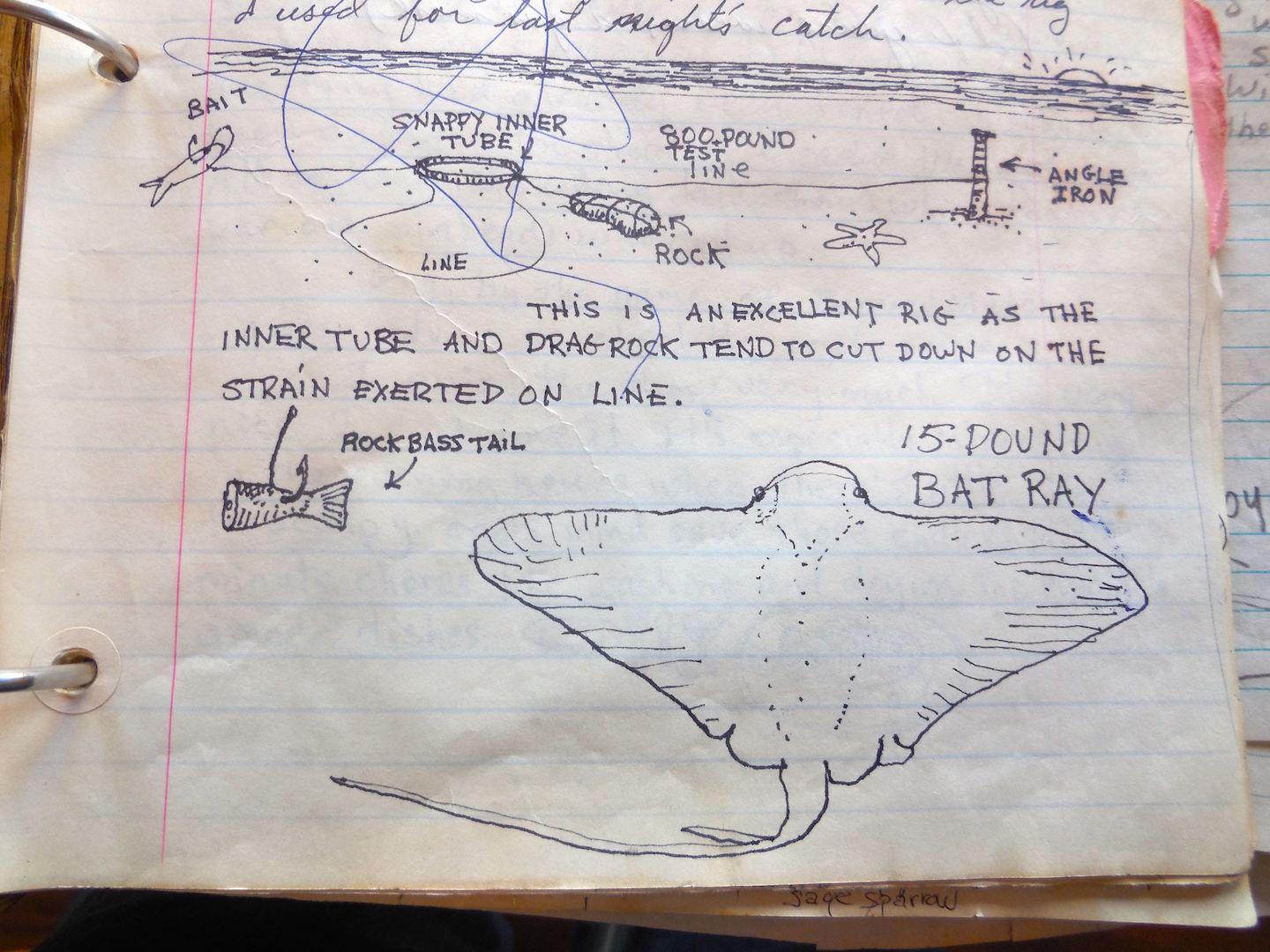

bat ray rig Enderezado y HQ Recortado.jpg

Bat Ray Rig.jpg

Kastmaster castmaster.jpg

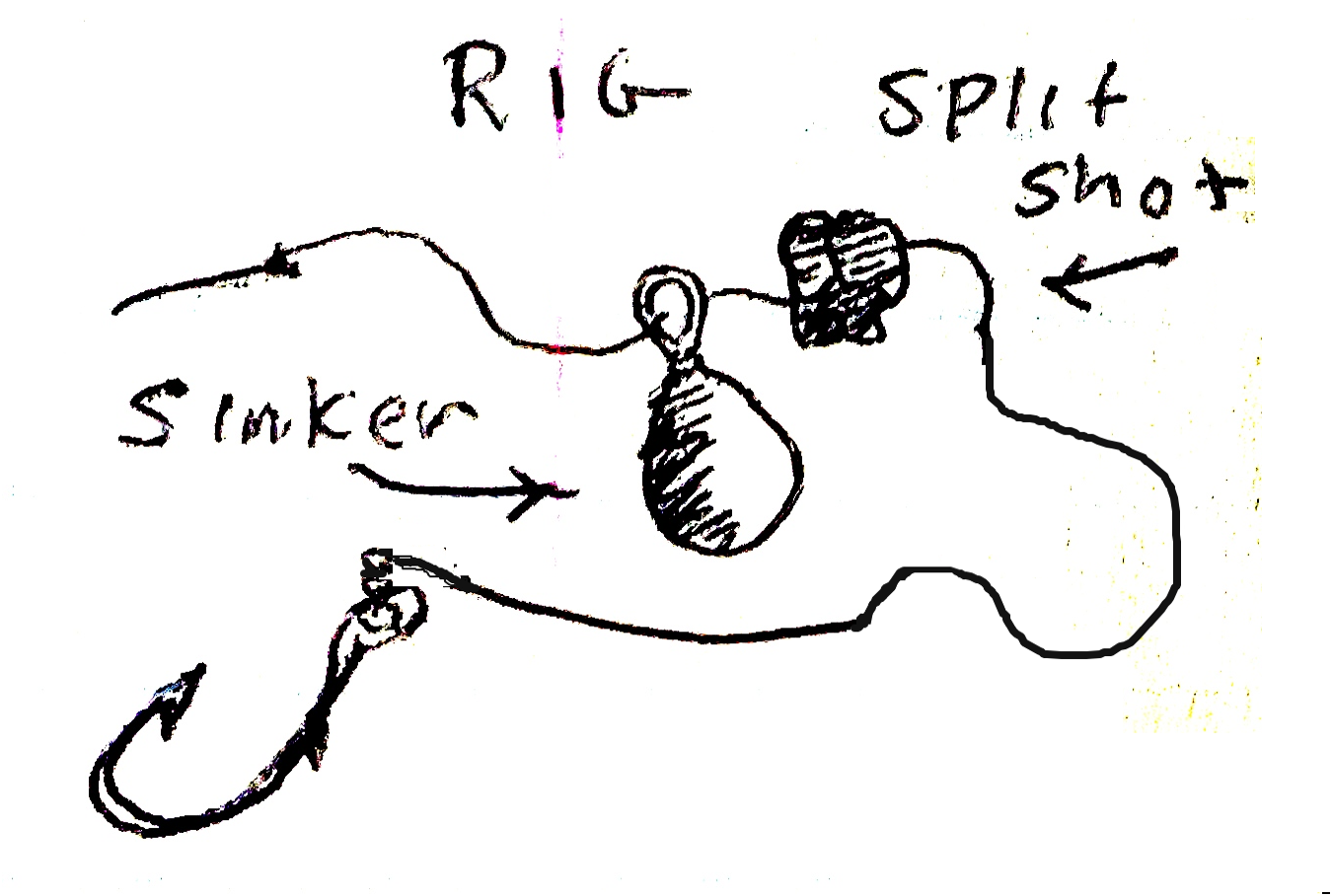

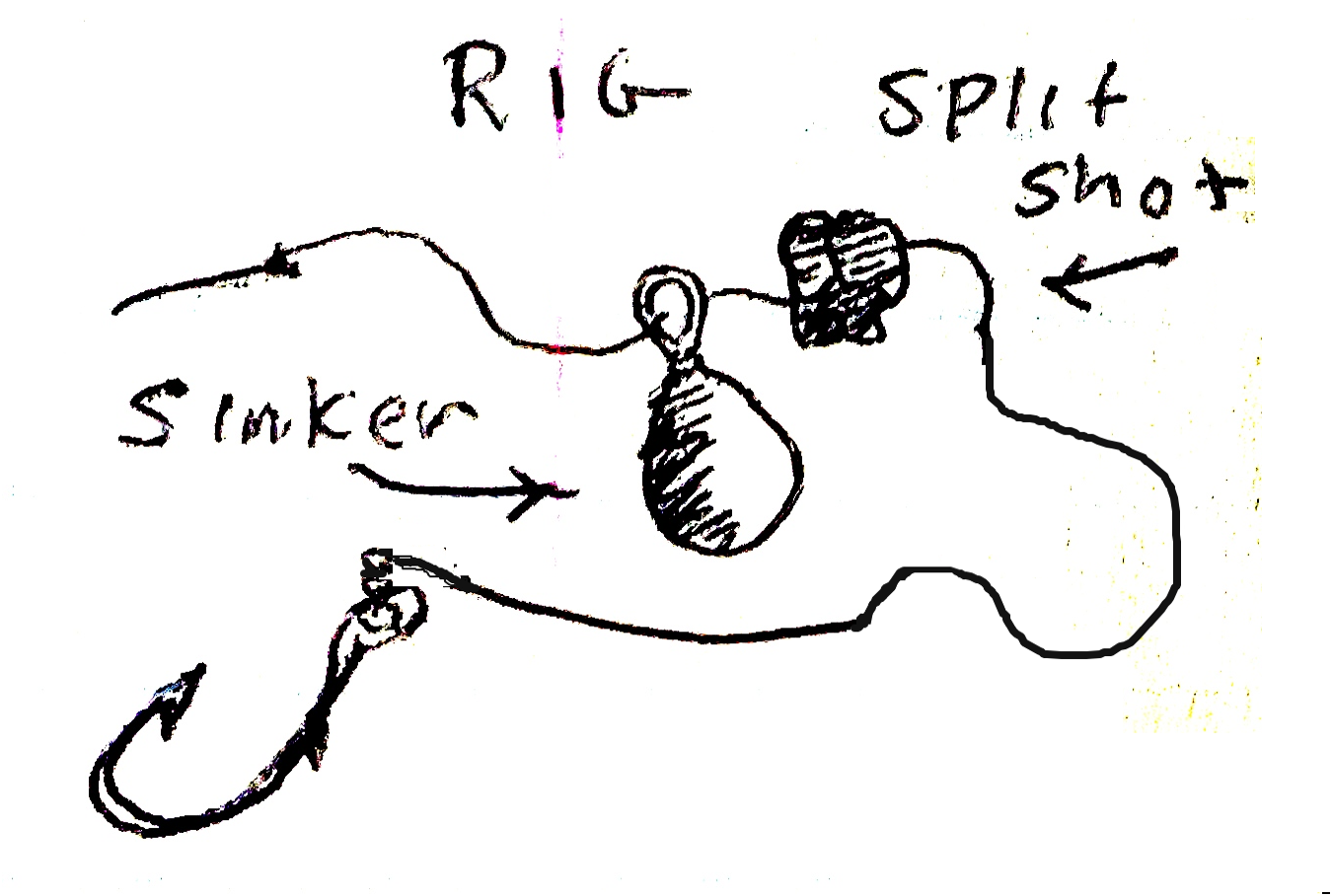

sinker rig redone.png

STEVE'S FISHING KNIFE BELOW

fishing knife1.jpg

fishing knife2.jpg

Tom Hascall's fly Rod A.JPG

Here's a Lure I almost got hooked on so when Jeff

came I borrowed his wine cork to make it safer.

It's big; you could catch ME with it EASY.

Fishing Lure with Wine Cork.jpg

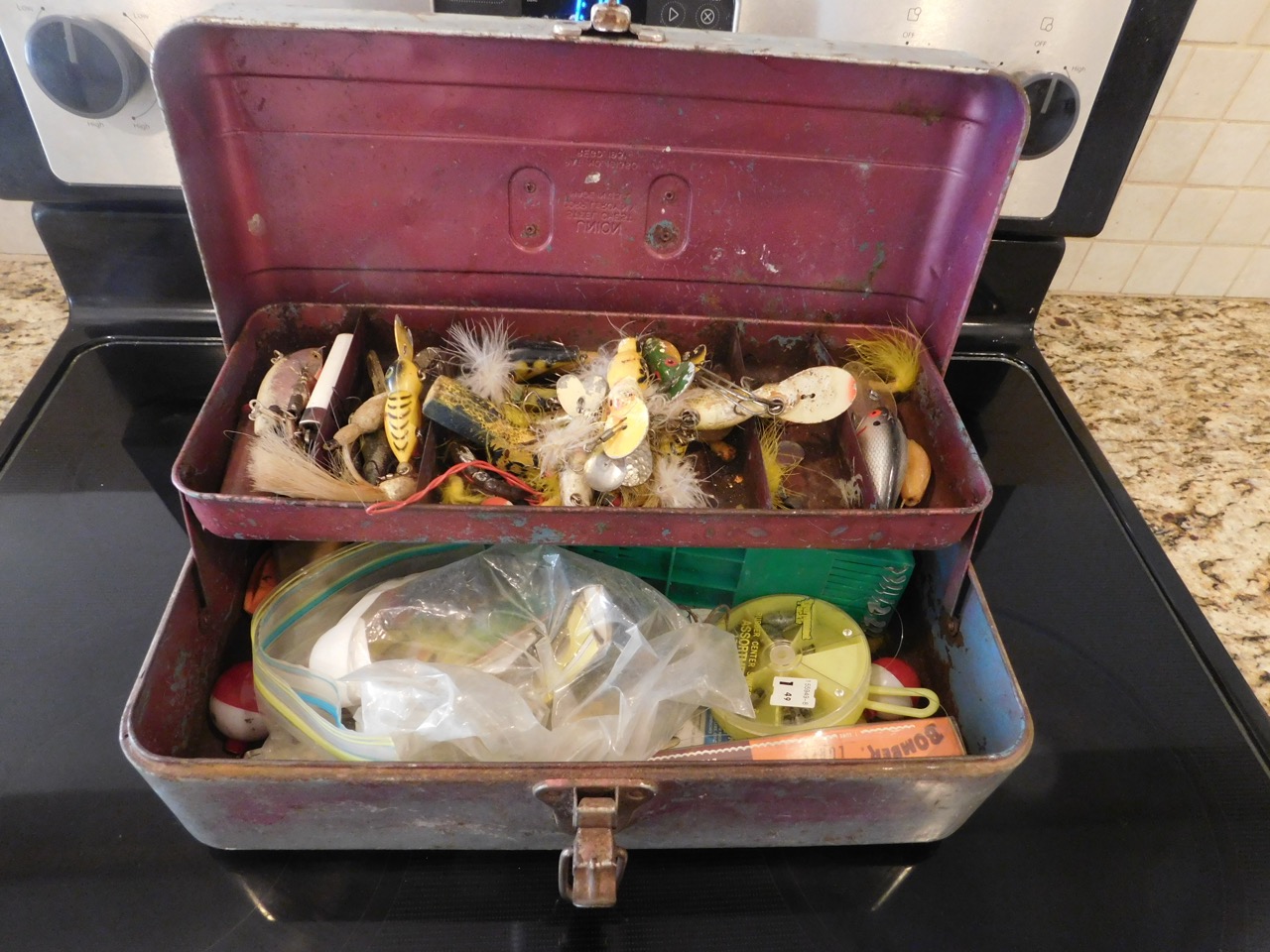

ALSO HOME NOVEMBER 2019:

TACKLE BOX CONTENTS

Mexican Tackle Box Contents.jpg

Yellowfront Tag.jpg

Fed Mart 9-volt Battery very rare.jpg

Hu Ting Fishing Supplies.jpg

From my Book Gone Are the Days

fishing lures at Dits house feb 21, 2022.jpg

usery mountain pass feb 21, 2022d.jpg

usery mountain pass feb 21, 2022b.jpg

fishing lures at Dits house feb 21, 2022cc.jpg

Stephen Cole

The

Castmasters

It was

in June 1963 that my father somehow got

his hands on an old Mexican panga equipped

with a 25-horse Evinrude outboard and took

my brother and me fishing near the Moruan

Estuary on Mexico’s Sea of Cortez. I

was twelve years old. We’d fished plently

from the shore but we were about to

discover that a boat makes a hell of a

difference.

Before our fishing trip, my father

gave us a little lecture about the

boat. He told us what trim ship meant

and baited us into using unnautical terms in

order that he might humiliate us.

First he tricked Tom into referring to the

stern as the back of the boat and gleefully

admonished him. “Stern!” he hollered,

feigning disbelief.

“Stern,” Tom repeated, ashamed.

Next, he led me toward the bow and deceived

me into calling it the front.

“Bow!” he hollered, rolling his eyes.

“Bow,” I said.

Dad was in high spirits. As he was

maneuvering the boat into the gentle waves,

he succeeded with various deliberate

misdirections to solicit the words right and

left. “Starboard!” he cried.

“Port!” he cried. He was having a good

time. The objects of this indignity

were not.

Fortunately, these four words comprised the

sum total of my father’s nautical vocabulary

and he was unable to perpetrate any more of

this fraud. Sensing this, my brother

and I proceeded to get even. My

father was not only about to reap what he so

richly deserved, he was also about to learn

how dangerous a little knowledge can be,

particularly when it is used to someone

else’s disadvantage.

Casually, and in all innocence, we asked

him to translate other items to nautical

terms. Both of us were eager to learn

we said. The old man was in

trouble. Perhaps he felt an abstract

sense of danger that he couldn’t quite name,

something dark and primitive. Tom and

I circled like wolves. I pointed to

the transom. “What’s this part of the

boat called?” I asked.

We were not kind. When we had

finished our survey of the panga, we dredged

from our memories the curious features of

other vessels: punts, dories, tugboats,

fishing smacks, sloops, mine sweepers,

submarines and bathyspheres, and asked for

translations. By the time the

inquisition was finished, my father had been

forced to reveal that in addition to the

word transom, he was unposted of the

following terms as well: thwart; stem;

cleats; sheer line; chine; beam; luff; reef

cringle; clew; leech; bowsprit; forefoot;

rutter skeg; taffrail; spar; halyard;

davits; rub rail; hawsehole; pudding fender;

capstan; scupper; and towing howser. He was

hoarse from saying, “I don’t know,” and

didn’t bother us any more.

Feeling well-avenged, Tom and I now got

down to business. Between us on the

floor (deck) of the boat were two opened

tackle boxes and in the unfolded trays of

these intricate cases, glinting in their

little rectangular compartments, were

objects we handled with reverence, beautiful

things made of brass and steel, feathers,

plastic, and enameled wood. Some had

metal blades that glittered like gems and

others caught the light and swirled it in

tiny iridescent pools so that the shelves of

the tackle boxes might have been lined with

black felt. They were living fetishes

with real glass eyes, and Christian names,

things upon which had been lavished such

craft that they seemed like small sentient

creatures bestowed by the gods of fishing

with tiny souls.

“I guess I’ll try the Little Cleo to

start,” I said. “We can troll out to

where Dad thinks the reef is and then anchor

and bait fish on the bottom.” I

clipped the silver spoon onto my line.

“Lemme see your swivel clip,” Tom

said.

I held up the line and the little Cleo

turned slowly in the bright sun and the

water and the sky whirled in its mirrored

surface. Each turn revealed a

little bare-breasted dancing girl

drop-forged on the concave metal.

“That’s a pretty small clip.” he

said.

“I know,” I said, “but I figure a big clip

affects the action.”

“Me too. A big swivel clip might be

easier to fasten and it might even be

stronger, but it’ll not only mess up the

action, but the fish can see it.

That’s my theory anyway.”

“I guess most people come to that

conclusion eventually,” I said. “Of course

for those big groupers you can use the

biggest clip you have.”

“Absolutely,” Tom agreed. “Not to

mention a steel leader. You got any?”

“Sure have.”

“What brand?”

“Tournament. Got them at

Yellowfront.”

“A lot of good those’ll do you when they

break,” he said.

“What kind have you got?”

“Eagle Claw. Twenty-five cents a

throw. Three to a package.”

I whistled to show I was impressed.

“You were probably right to pop for those,”

I admitted. “If you’ve got any extra

maybe you’ll lend me one.”

“Sure. I got plenty.”

“Thanks. Say, what are you going to

troll with?”

Tom looked thoughtfully into the tackle

box. “Well, I’m not sure,” he

said. “These River Runts and Lazy Ikes

are pretty useless in the ocean I guess.”

“You never can tell,” I said. “How

about that Bomber Waterdog or maybe the

Cisco Kid?”

“Naw. I’ think I”ll use a spoon.

Besides, I’m afraid I might lose the Cisco

Kid.”

“Don’t you ever fish it?”

“Nope. I sent away for it

special. It put me back

plenty. I’d be a fool to risk losing

it.”

“What about that Paladin? It looks

deadly.”

“It looks deadly all right but the fish

don’t like it. I’ve never gotten a

strike on it.”

“I’m surprised, Tom. Look at how that

blue metal flake glitters, and that chrome

lip. Not to mention the

eyes. Godamn, but the thing just looks

alive. The pupils even swivel around.”

“I know. It’s a quality plug.

The plastic doesn’t even have a seam.

It’s all I can do to keep from biting it

myself. But the fish think different.”

I thought a moment and then said

philosophically, “I suppose fish just don’t

appreciate the art of it-- just don’t have

the head for that sort of thing.” I

picked up the heavy lure and turned it in my

hand and the sun gleamed on the chrome

fittings. The white plastic was like

ivory and the blue glitter design in the

finish seemed to sparkle in the air around

it. The little black pupils clicked

like tiny dominoes. “It’s just plain

over-built .” I pondered this a

moment. Then I looked into my tackle

box. “Funny... all these lures are.“

Tom clipped on a half-ounce

Castmaster and lobbed it out behind the

boat. It skipped on the surface in the

wake.

I yelled aft. “Slow her down,

Dad. We’re going to troll now.”

Dad cut the speed until the boat was

just barely chugging along.

“Just a touch faster.”

“A touch faster,” he said, and the engine

picked up a little.

I cast the Little Cleo far behind the

boat. Then I let the line run out even

farther as the boat moved ahead. When

I figured I had enough line out, I set the

reel and leaned back. Through the line

I could feel the lively wobble of the Little

Cleo and knew the bait was running smoothly,

not tangled up. The casting of the

lure had been done well and I was

satisfied. For part of me believed, or

half-believed, that I was not just casting a

line, but a charm over the waters, a spell

that would enchant the fish, and the magic I

was working could be broken if the ritual of

it were done poorly or gracelessly.

“We’ve got about a half mile to where I

think the reef is,” Dad said.

“Wham. Something hit the Little

Cleo. It was hooked and running.

“Cut the power!” I yelled. Dad

throttled down to nothing.

Despite my age, I already had

developed the instincts of a good angler and

the sensations that came through the line

told me that this was a leatherjacket.

No other fish in the estuary fought like

it. It was easy to tell the

difference. A leatherjacket was

snappier, and fought in tighter angles than

say a Corvina that fought hard but with a

blunter edge. A leatherjacket always

sent through the monofilament a feral

electricity that I could recognize as one

might a particular person’s voice.

Leatherjackets always fought up on top

of the water too, whipping around near the

surface.

I worked the fish carefully toward the

boat. Twenty feet out it jumped and

flashed brightly in the sun and I kept the

line tight as not to let the fish shake off

the lure.

I took my time. It was always a good

idea to try to wear out a

leatherjacket. Brought in too green a

little leatherjacket could wreck havoc in a

boat, bouncing up in your face and slapping

tackle around. In addition to this,

the little fish had cruel spines which left

painful punctures. It was difficult to

handle even a dead one without getting

stuck.

I got the fish aboard and removed the

hook. Tom and I admired the fish where

it lay on the boat bottom. It was the

whitest of silver and it was a good size for

a leatherjacket, well over a foot

long.

We both thought the fish was beaten but we

were in for a surprise. Without

prelude it bolted into the air like a

jackrabbit and disappeared over the

side. It happened so unexpectedly that

we were surprised into laughter. We were

glad he got away.

Then the motor rose up to trolling speed

and it was Tom’s turn. His line,

which had been lying on the bottom, took up

its slack. The Castmaster rose out of

the sand and perhaps flashed only once

before it was hit hard. Tom was

startled by the power of the strike.

“Holy cow! Now I’ve got one.” he

yelled.

Again the motor was cut and the fish

played.

“What do you think you’ve got?” I asked.

“Hard to tell. Hooked him down on the

bottom so it can’t be another

leatherjacket. Besides, he isn’t

fighting like one. He’s clunking his

head around.”

“Sounds like a puffer.”

“Maybe. But look at the long runs

he’s making. Besides, since when’s a

puffer hit a spoon? My bet is a sargo,

or maybe a porgie.

Tom’s first guess was right. As he

brought the fish in we could see the

characteristic lightning stroke marking of a

sargo. Careful not to horse him, Tom

brought the fish to the side and flipped him

in. He was a little disappointed.

“These sargos always seem huge until you

get them out of the water,” I said.

We trolled on to the reef without any

strikes for a while. Then, just as our

attention spans were reaching their limits,

the boat crossed a mass of Corvina, what we

called sea trout, moving into the

estero. Neither of us would have

called it a school. The word was

somehow inaccurate in describing a sea trout

run. It did not capture the

largesse of the event. These fish

moved in herds like wilderbeasts and when

they appeared in the estuary the alarm would

go up. People would holler, “The sea

trout are running!” and this would

cause a frantic dash to the beach. For

an hour there would be a madhouse of fishing

with people lugging around buckets stuffed

with fish, falling over each other and

spilling them, and anglers slinging fish up

on the beach and running back down to catch

more. And for that magic hour the

world was transformed. Gone was all

envy or avarice and no fisherman

begrudged a fish or harvested any of

the sea’s luck at the expense of

another. All secrets disappeared and

the most avaricious of fishermen, without

even being asked might shout to anyone and

everyone, “They’re really hitting on Spin

Rites!”

Tom and I hauled in corvinas until our arms

ached and then the herd moved on and the sea

was quiet around us. We kept two of

the biggest hung over the side on a clip

stringer.

“Well, that was sport, all right,” I said,

“but you can have that kind of fun from the

shore. We shouldn’t be wasting our

time with sea trout when we’ve got a

boat. How far to the reef, Dad?”

My father looked toward the shore and then

out across the bay.

“I figure we’re just about on top of it

now. Why don’t one of you guys look

over and see if you can spot it.”

Tom leaned over the side and squinted into

the water.

“Well?”

“Nothing, I don’t think. It looks

dark down there but I can’t tell whether

it’s rocks or just deep.”

I leaned over and took a look. “I say

it’s rocks. Throw over the anchor.”

The anchor line reached down thirty feet

before it touched bottom. Tom secured

it to the bow but it wasn’t long before we

realized it wasn’t holding. The

current of the rising tide was moving the

boat in toward the opening of the estuary

and the anchor, a big paint can full of

hardened cement with the round end of an eye

bolt sticking out, was dragging across the

sand.

“We should have a plow anchor, “ Tom

said. It’d dig into the sand and hold

us.”

I was exasperated.

“Sand? We don’t want any sand,

dumbbell. What’s the matter with

you? We’re suppose to be over rock, a

reef with groupers swimming all over

it. We’ve got to get that motor fired

up and keep looking...”

There was a little jerk. The anchor

had caught on something. The

line was now taut with little drops of water

jumping off it and the current now seemed to

flow around the boat.

“I think we just hit the reef,” Tom

said.

“We couldn’t have done anything

else. We’ve stopped dead

still. That anchor is hung up on rocks

down there.”

Tom and I looked at each other for a moment

and then dove for the bait bucket. In

less than a minute our lines were

slip-rigged with egg sinkers, steel leaders

and size four-0 hooks baited with big squid

heads dripping purple ink.

Times of Subdued Light

Anchored over the reef we had a view of

everything. Northwest was the

Sierra Blanca which lay on the desert like a

dead stegasaurus and behind it loomed the

black Pinacates, an immense volcanic

wilderness of huge cindercones and

craters. It was the rising of these

volcanic mountains that had in ages past,

diverted the Sonoita river and created the

Moruan estuary. To the northeast

horizon lay lines and lines of jagged,

sand-colored mountains.

Jutting from the sea to the southeast were

the Bird Islands. From the estuary

they looked like three pyramids on the

distant horizon. It was one of my

pleasant habits to imagine I was looking

across the sea to Egypt. But this was

not possible every day for the curious

optics of the gulf caused the islands to

change shape. On some days they

resembled not pyramids but distorted

mushrooms growing out of the sea, on other

days, jutting columns of rock like those

at monument valley. Still other

days when layers of cool and hot air made a

particularly shaped lens, the islands seemed

to defy gravity. At such times they

floated above the water, in the sky, these

pyramids or mushrooms or rocky

monuments. And none of this seemed

unusual. There was magic everywhere in

the gulf.

The air and the sea had merged and the day

had become hazy and dreamy. The little

boat floated lightly on the water and above

it white gulls swirled in the blue

sky. No one spoke. My father

leaned back against the sun-faded, pale blue

Evinrude motor and dozed. Tom and I

were drowsy too, mesmerized by the wobbling

sun on the waves. Our lines, almost

forgotten, drooped languidly into the deep

green water.

My eyes moved lazily to the dunes that

loomed over the long sandy beach.

Lulled by the sun and water, my mind drifted

pleasantly. I closed my eyes and

thought, or dreamt perhaps, about the

pristine surface of the dunes and the secret

traces left there by wandering coyotes.

There were trails in the sand, paths that

led through a desert wilderness of rock and

creosote and cholla. I had discovered

them during last year’s visit and thoughts

of the sand trails and where they might lead

had haunted my dreams that whole week.

Now the strange, nameless feeling called up

by the trails was back.

I remembered that near the beach, on a

dune, a path angled down like the stripe on

a fish, faint , barely marring the

silt. I had recognized it for what it

was, part of a secret highway, a network of

trails that connected the dunes with the

desert and the mountains--a wilderness route

that led into the night, a strange geometric

design, as indecipherable as cave paintings

or the lines on an astronomer’s chart.

I was the only person in the world who knew

this secret.

In my dreams I had hiked these roads and in

the mists of my imagination had pictured

what lay where the sand trails ended.

Once a huge stone face appeared half-buried

in sand. Neither Egyptian nor Olmec,

the face belonged to a civilization created

in my dreams, the remnants of a lost

city, a Sphinx quarried from Sonoran

granite. On another night my

wanderings might lead me through sahuaro and

ocotillo to a simple circle of

stones.

It was likely that the trails led to

nothing more astonishing than a dusty cave,

or a brackish seep in the desert, or a small

pool of rain held in the fluted granite of

the mountains where coyotes might drink, and

I knew this. Still their mystery was

irresistible and as seductive as the voices

of sirens.

I opened my eyes and these images of night

gave way to spears of sunlight thrown off by

the water. I squinted and my vision,

washed out by the sun, came slowly back as

the green and blue of the estuary ran across

my eyes like water colors. Looking to

the shore, I could now see figures moving on

the beach, one clad in yellow, the other

blue. They were running in the

shallows, and appeared to be throwing a

ball.

All at once I was possessed of an

urgency to get to shore. Without any

warning at all, my mind had taken a hairpin

turn. Why in the world, I thought, was

I floating in a smelly boat, a bucket

of purple squid between my feet when

girls frolicked in swimsuits on

the beach? I tried to find one

rational explanation for it. I

couldn’t. It was crazy, I concluded,

and I shook my head and whimpered a little

at the senselessness of it. Never before had

the absurdity of fishing become more

apparent. The obsessive casting of

lines! And for what? After all

the effort, the study, the expense, what did

any angler ever have to show for himself

other than a lousy fish? Just what was

the allure in this mystical casting of

lines, I asked. Just what was it I was

searching for? For a moment a vision

of Little Cleo appeared in my mind and began

to sparkle and spin and then the rod

came alive in my hands and the shallow,

blasphemous thoughts disappeared forever.

It was a steady pull. Deep near the

bottom, heavy. Instinctively I knew I

had never hooked anything like it

before. Tom was already reeling in his

line. He saw by the bend in my rod

that this fish would need plenty of

room. He didn’t want to be blamed if

he tangled him up. Then he remembered

the stringered sea trout and slung them into

the boat and out of my way.

I raised the rod and calmly reeled in a few

feet.

“He’s big, but not so big I can’t move

him,” I said. “He hardly knows he’s

hooked yet.”

It was quiet in the boat. We were

almost whispering.

Tom spoke calmly. “He’s thirty feet down,

remember. Better get some line back

before he starts running,” he advised.

Slowly, ponderously the fish moved around

the stern. I followed carefully

around the boat, my rod bowed in a half

circle and in the hot sun the bluegreen

monofilament as bright as neon pointed

straight down into the water.

“I’m going to have to horse him a little,”

I said. “Otherwise he’ll do exactly

what he pleases. Maybe we can pull up

the anchor and float with him.”

My father, who had been staying out

of it, now moved up to the bow and hand over

hand, started bringing up the anchor.

I pulled back hard on the rod and then

dipped the tip back to the water as I reeled

in line. I repeated this several

times, always careful not to create any

slack. I had moved the big fish high

off the reef before it came alive and

started taking back line. There was no

stopping it. My tackle was

ridiculously light for this fish. The

reel screeched as the puny ten pound test

was stripped off the spool.

“Can you stop him?” Tom asked.

“No,” I said. “He’s a tank.

Maybe he’ll stop on his own.”

The fish was running down and away from the

boat. A hundred yards of monofilament

disappeared from the reel before it

stopped. I knew I had only a few feet

of line left and that I had to get it

back. If he ran out the spool it would

be all over. The line would break like

dried spaghetti.

I wondered if he had enough talent to land

such a fish. I thought I might.

Even then I’d need more luck than I should

expect. But a share of good

fortune started when the anchor was heaved

aboard.

Up until now, I had been fighting from a

solid platform. This gave the fish an

advantage. It had only to run out my

line and break it off the spool. But

now the fish was moving again and the boat

seemed to follow. It was as if the

fish were pulling it into the estuary.

This was not entirely an illusion.

While the current was doing most of the

work, the fish was pulling too, and now that

the boat was free, it gave a little when the

fish pulled. This added to the effect

of the yielding drag and the bending rod and

the fish had that much less power to tear

loose or break the line.

Fish and Panga were headed slowly into the

estuary. The tide was almost at its

highest but the current was still

strong. A wind picking up astern

pushed the boat along too. Again

fortune seemed in my corner. The speed

of the drifting boat had begun to overtake

the swimming fish. I was finding it

easier to reel in line. In fact, it

soon was necessary to pump fast to draw in

the slack.

The water was shallower here, the color

lighter, more blue than green and at times

we could see dark patches of seaweed glide

by under the drifting boat. It wasn’t

long before we were closing in on the fish

who up until now had been moving with

confidence feeling in complete control of

things. Now the boat was on top of him

and the line which had heretofore felt so

light in his jaw was now solid and

menacing. He panicked.

The fish bolted away like a torpedo and

this time it didn’t appear he would stop

anytime soon. My little black reel

squawked in my hands like a crow as the line

whipped out in the direction of the fleeing

fish.

“He’s going crazy!” Tom yelled.

“Man oh man! Look at

him!” I stood in the center of

the boat, my legs apart, holding the bent

rod helplessly. There was only one way

this could end. And then, a

miracle. The fish seemed to

stop. Something had happened under the

water. Perhaps near the bottom a

jutting sand bar, a little underwater shelf

of sorts, had startled the fish. He

skirted its edge and then, confused, turned

a half circle and fled back from where he’d

come, trailing a widening loop of line

behind him. Whatever it was, he was

coming back.

I stared vacantly for a moment at the limp

line hanging from my rod tip. I was

inclined to believe the fish had broken free

and was about to curse my luck when I

divined what had happened.

“He’s changed direction,” I said suddenly.

Tom stared blankly for a moment and

then guessing I was right, regained his

wits. “Start cranking!” he said.

“Get that slack in. He’s coming back

at us!”

I reeled until I felt the swimming

fish. The line was moving into the

current and past the stern. I horsed

him a little and the fish turned back and

made a third run with the tide. The

boat, still drifting into the big estero,

followed.

“I think he’s running out of steam,” I

said. “If I keep drifting up on him

and getting back my line, he’ll eventually

wear himself out.”

“Don’t sell him short, Steve.” Tom

warned. “You haven’t got him

outsmarted yet. There’s no telling

what he’ll do.”

“That’s true,” I admitted. “But at

least I’ve got a plan now. If I can

stick with it we’re going to have grouper

for dinner tonight.”

Tom watched as I worked the rod and

reel. The sun shone through the green

glass rod and the line was taut and hissing

where it cut the water.

Dad was sitting in the bow smoking.

He hadn’t said a word the whole time.

He wasn’t butting in with unappreciated

advice or ignorant suggestions or piscian

nomenclature and this was wise, for the

truth of the matter was that while he had

more degrees than a thermometer, he didn’t

know shit about fishing. Aside from

the nautical terms baloney at the beginning,

the man had behaved like an angel.

That is, he behaved like he didn’t exist,

and Tom and I who had little use for

adults, appreciated it. After all, we

were professionals, impatient with amateurs.

Most of our knowledge had come from

experience fishing the canals and ponds in

the river bottom near our home in Tempe, or

during those long summers at the biology

station on Lake Itasca in Minnesota.

But a lot was acquired from reading.

Tom had a book called Fishes of the World,

for instance, which contained pages and

pages of black and white photos of fish and

essential information on each. He also

had the Gulf of California Fishwatchers

Guide We had spent hours pouring over

both.

“You’re figuring he’s a grouper then?” Tom

said.

“Why not? That’s what we’re after,

isn’t it?”

“Sure, but there’s a lot of other things it

might be. All kinds of fish hang out around

a reef. Could be a big sea bass, or

even an outsized pinto.”

“Naw.” I said. “Pinto bass don’t get

that big unless I’ve got a world record

which is fine with me. A big sea bass,

sure. Could be.”

“I hope it’s not a big diamond ray or bat

ray,” Tom offered and right away

regretted saying it. By the jerking of

the rod alone he already knew it

wasn’t. Now his careless comment was

open to criticism.”

“A ray?” I scoffed. “I guess I know a

ray when I hook one. A ray just pulls

and when he takes off he accelerates like a

car. You can feel by the way one

fights that he hasn’t got a

tail. A ray won’t cut any didoes

either. No, this isn’t any ray,

Tom. I’m surprised you said it.

Hell, I can feel the shape of him right

through the line.”

Tom took this rebuff without comment and

then said, “Maybe it’s something we haven’t

considered.”

This was an interesting thought. I

looked up from my careful reeling.

“Well, go ahead and consider. I’m

listening. We’ve eliminated the rays

of course, but aside from a big sea bass or

grouper, what are you thinking?”

“I don’t know, but there’s plenty of fish

in this gulf besides those. I’ve got the

fishes of the gulf book in my tackle

box. Maybe it’s one of those big

electric cats you claim are out here, or

a Barred Pargo.

“That’s okay with me,” I said. “I’m

not worried about the electrical cats

either. Not in in this boat anyway.

It’s all wood and fiberglass. Besides

we’re wearing rubber sneakers.”

Then Tom had an another inspiration.

“The Colorado river empties into this gulf

just northwest of here,” he

said. “Maybe you’ve hooked a

giant sea-run river squawfish.”

This was a wonderful thought.

“Wouldn’t that be something,” I said.

We lapsed into silence then as I

played the fish. We were both

imagining a huge river minnow drooped over

the bow or trailing on a rope behind the

panga like a pursuing sea serpent.

Maybe people on shore would scream out

warnings as we motored in, and Tom and I

would beach the boat and laugh and haul the

long behemoth up on the sand while

astonished tourists rushed over to take

snapshots.

Meanwhile, the plan seemed to be

working. Three times I regained my

line and three times the big fish took it

back. It looked like I was winning the

fight, although I was worried about the

drag. It was sticking. On that

last rush the line nearly broke before the

drag let go.

By now the panga had drifted well

into the estero and it was time to either

catch this fish or lose him. My

brother and I worked as a team while my

father prudently kept out of the way, his

big mouth shut. Tom had the large net

ready and both tackle boxes closed and

latched and stowed as I moved the tired fish

up toward the surface. We were about to get

our first glimpse of him. He was about

four feet under when he came into view for

just a moment. Then he saw the boat,

and took off flashing bright red. The

color startled us. What kind of fish

could this be? I had no time to

speculate. The drag was stuck and the

fish an inch away from breaking the

line. I pushed the button and opened

the spool and then held the line against the

rod with my thumb as it played out.

The drag was shot, but I was confident

now. I’d worn the fish down. I

clicked the Zebco back into gear and started

pumping hard. It was time to show who

was boss. I moved the fish up rudely,

strong-armed, forced him toward the

surface. I wasn’t horsing him.

What I was doing was different, and with

this thought I felt a little rush of

pride.

I could hardly remember when the fish broke

the surface, huge and red and blue with big

pectoral fins that spread out like

wings. The animal floated just under

the green skin of the water, moments away

from making a last desperate run. But

Tom was there with the big net and with one

motion scooped up the fish and with both

arms straining, heaved it crashing into the

middle of the boat. I fell on it and

hugged it to the smelly boat bottom.

One of the gill plates slashed my hand but I

held fast. I was remembering the

leatherjacket’s escape and knew I could not

bear that happening now. The fish got

his wind back for a moment and kicked some,

but there was not much fight left in

him. I held on until he was still and

then got up from the boat bottom and

sat back on the bench. The fish would

weigh in at twenty-one and a half

pounds. I had taken him on ten pound

test.

Tom opened his tackle box and got out the

fish book while the panga drifted with the

tide. He thumbed through it a while

and then stopped on page 36.

DOG SNAPPER, Pargo prieto, Boca fuerte

Lutjanis novemfasciatus

Body reddish, darker on back and fins with

about nine bars on sides. Two large canine

teeth on upper and lower jaws. Blue

streak under the eye. Feeds on fishes

crabs and shrimp at times of subdued light

and at night. Largest Gulf snapper:

Common throughout the gulf south to Panama.

To 85 pounds

I looked at the drawing and read the

description. That was him all

right-- all except the part about

subdued light. I had no idea why the

fish was feeding in such bright

sunshine. But the rest of the

description was right, or factually right,

anyway. For as I read it a second

time, I found that there was something

amiss, a subtlety the book could not

capture. I looked down at the big fish

where it lay dead on the boat bottom.

It was the greatest fish in the

world.

�

Dear Steve,

Fishing in the Salt river is a joke.

Nine days out of ten a guy could piss a

bigger river than what that Salt is and the

fish have developed lungs, fur some of them

because there just plain isn’t enough water

to go around. No, don’t argue it

because that just happens to be a

fact. The only way to get any sport

out of fish like that is with .22 hollow

points and a good dog to flush them out of

the brush.”

But the sea doesn’t contain any such

kind of fishes as that dumb river.

It’s there damn near 365 days a year and the

fish get fat and sassy. Channel

catfish! Phssft! Do you know

that sea cats can direct their spines?

Yeah, they can, like a stingray. And

I’ll tell you something else also.

They’re electrical, some of them. You

hook one of them and you better have the

sense to cut your line or you’ll just flat

wind up fried to a crackling crunch.

There’re documented cases-- and I said

documented cases-- of anglers-- good strong

men some of them too--- who’ve reel-pumped

those big electric cats and let them slap

against their metal boats. The current

was so strong it oxidized those boats.

Turned them all into aluminum oxide-- silver

onyx-- and they sank like bolo ties.

Broke up before they ever reached

shore. Not a one of them ever came

back, and nobody ever found out what

happened to them.”

A real fisherman goes for the

lunkers. Well, let me tell you

something then. The big fish are out

in the ocean and you don’t catch them by

wading in the surf and developing

acherry toe and salt water pickle

combo. You get a boat with a live

well, a spitoon and an ice chest full of

beer and you head for deep water where the

groupers are so big they eat skipjacks like

peanuts.”

Yours,

Tom

Dear Steve,

A fisherman knows his

skills and he knows that with two feet of

kite string and a bent nail, he can haul in

anything that swims. It’s a

gift. He’s always had it. He

falls in a mud puddle and comes up with a

king mackerel. But he usually heads

for deep water. A Good panga and a

twenty-five horse Evinrude’ll usually do

fine. He throws a line over the side

and tells his buddy to out with the .45 auto

because a real fisherman expects trouble any

time he wets a line. He doesn’t let it

catch him unsuspecting. He doesn’t let

a fish make a clown of him. He doesn’t

believe in God or miracles and he doesn’t

let a friend use a rifle because the kind of

fish he wants to catch would grab it by the

barrel and beat both of them over the head

with it. There’s been cases,

documented ones, where this has

happened. That’s a fishing trip,

mister.

Yours,

Tom

Stephen West Cole

Then of course there was Field and Stream

which contained the usual articles which

have scarcely changed to this day. The

stories in that magazine so dazzled us with

their description of a world of men and the

out-of-doors that despite our perhaps

average intelligence, we were close to

believing in its existence. The

articles went something like this:

I’ve known a lot

of guides. Take that Bill

Furson. Tough as nails and dusty as

old tennis shoes. Or Jake

Randleman. Well, a man might have

lived who could out trap him, but there

never was a more earnest salmon-gigger

born and that’s a fact. Why, I remember

him stalking them big bull moose at a

waterhole and just cruising under the

surface like an alligator. Didn’t

sog up his rifle none either. Old

Bell Clay might have out- guided the both

of them if it weren’t for that pin

leg. Still, you don’t find the likes

of them anymore. Not nowadays

anyway. But Koot Too, genuine

Brachiopod Indian, could outdo even the

best of these fellers. Why, I once

saw that feller take on a birch tree with

a Bowie knife and with just two strokes,

slice a canoe off the side...

|