THE WEB; MY TRUCK; THE TUNA, FRUIT, AND BEER DIET; THE HIGHWAY TO TUCSON; THE SONORAN DESERT ENDS; SALOONS, KARAOKE, AND LOCAL YOKELS; THE PRESERVE; PHAINOPEPLAS AND MISTLETOE; RAP ON BINOCULARS; THE HUMMINGBIRD FEEDERS; WRONG WAY TOM

I was on the web looking at the Maricopa Audubon Society's page when I saw that on July 29, 2000 there would be a trip to the southern Arizona town of Patagonia, population 200. I knew the place was renowned for its varied bird species and my friends Larry and Nancy had been there a million times. I figured it was time I made plans to go down myself to knock off a few life listers.

I told Larry and Nancy and they wanted to go but couldn't, so I phoned the trip leader and got on the list of participants alone. This meant that I had agreed to meet the people at the Nature Conservancy's preserve in Patagonia at 7:00 AM on a Sunday morning.

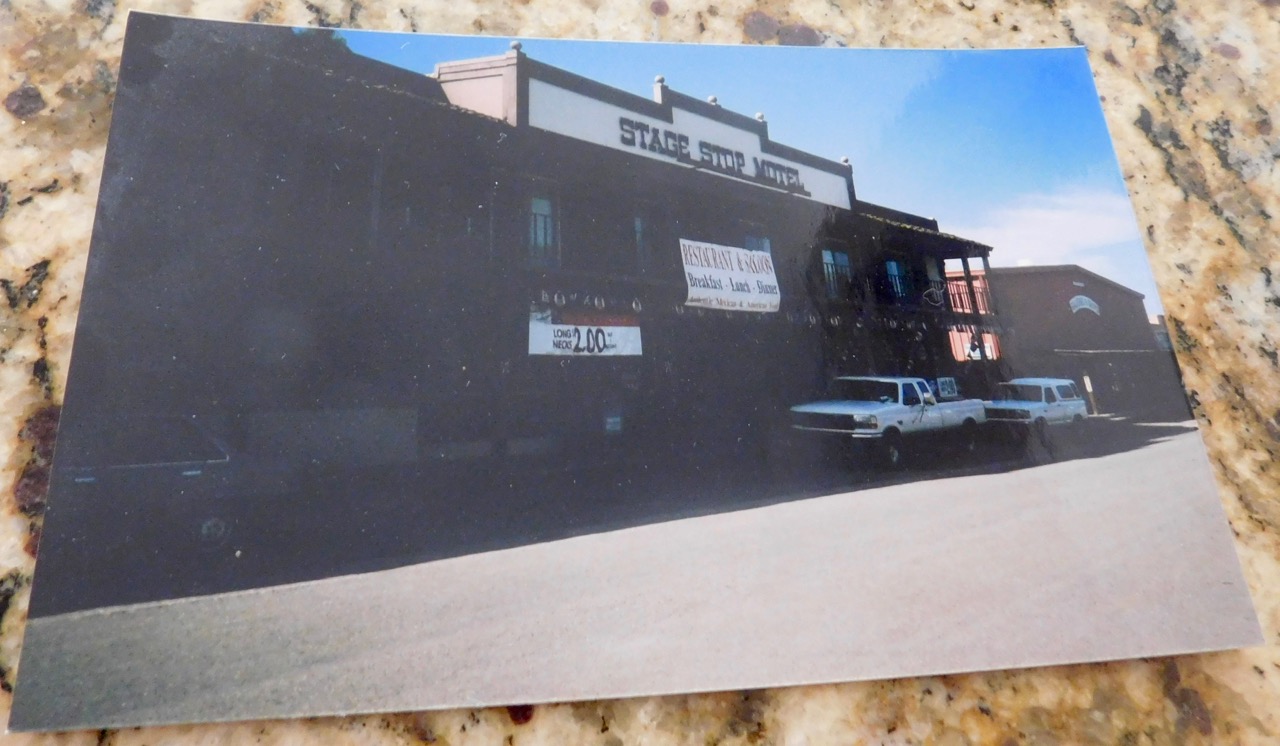

Patagonia is three hours from my home in Chandler and since I am incapable of getting up at 4:00 in the morning for a drive that far, I knew I would have to go down the day before and spend the night. I used the web again, found the only hotel in town, the Stage Stop Inn, and made a 55-dollar reservation. Larry and Nancy told me the place had a lounge and there were a couple of saloons down the street. Larry always likes to crack a beer to toast the conclusion of any day's bird watching, and I am always happy to join him.

Stage Stop Motel State Stop Inn Patagonia Arizona 2002.jpg

I made arrangements for my dog Noodles to be cared for and headed down towards Tucson on Interstate 10 at two in the afternoon. It just so happened that I was especially equipped for such a trip as I had very recently purchased a year 2000 Nissan Frontier pick-up with six cylinders, five gears, and four full-sized doors. It was very SUV-like and I felt fairly safe in the thing until I learned that these high-off-the-ground machines roll too easily. One bump from some careless bum on the road and my truck could turn over on the highway. I got the safety stats on my truck and was not happy with what I read. My brand new cruiser was a bowling ball.

I put a cooler on the back seat. It was loaded with pop and beer and some apples and pears. The apples and pears were to help me lose weight. An ectomorph and barely five feet eight inches tall, I knew it was time to do something when I began to push 200 pounds and so I had recently gone on a tuna, fruit, and beer diet and the trip was no occasion to go off of it. The diet, which I invented myself, is simple and effective: you can drink all of the beer you want and eat all of the tuna and fruit you want. That's it. Now, the tuna has to be packed in water instead of oil and technically the beer should be light beer.

The beauty of the diet is that you give up so little for it and it contains absolutely no fat. You can also more easily add exercise to it than with normal diets. This is because you can exercise and have a beer at the same time. It's a wonderful incentive. I go out to my patio and get on the running machine. It's as hot as hell out there, but I have a big fan hooked up that blows air on me. I also have a beer to cool me off and to give me the inclination to go out there and run. It's like my friend Jan's entrepreneurial dream: he wants to have his own bar and grill -- only he'll have washing machines and dryers in it so everyone can have a beer while they do their laundry. The principle is essentially the same.

I don't like the drive to Tucson. Interstate 10 is way too narrow and there is a steady barrage of huge trucks barreling back and forth between Phoenix and Tucson. In addition, the scenery is unremarkable, if not unattractive. For a better view you can take 89 south, the Tom Mix Highway. There's a lot of chain fruit cholla along it and it's quite scenic. On the side of the road is a memorial to Tom Mix because he got killed there speeding like a fool in a convertible and crashing into an arroyo. A heavy suitcase in the car came loose in the crash and bashed his brains in. The suitcase is on display in the Tom Mix Museum in Dewey, Oklahoma.As I drove I tried to pay attention and not let my usual spatial confusion set in. I stayed on I-10 and didn't foolishly get off it for some reason. The fact is, I have no sense of direction and can get lost anywhere at any time. I am simply brain dead with regard to my bearings. I admit it. I almost always make a wrong turn and wind up having to turn around and drive clean back to wherever I goofed up. Because of this, my own nickname for myself is Wrong Way Tom. This disorientation was a particularly dangerous problem for me many years ago when I became a pilot. In fact, when I went up for my test flight with the FAA guy, he told me to fly to a power tower on the map, but I couldn't find it and got lost. Finally he said, "All right, enough! Turn to three six zero degrees. You've been flying around in circles for twenty-five minutes!"

Highway 83 had rolling hills covered with green ocotillos. This, I realized, was no longer my familiar Sonoran Desert. Southeastern Arizona looks like no Arizona you ever saw. It's a mix between Nebraskan-like rolling hills and low chaparral and a touch of scraggly jungle. I hadn't seen any birds along the drive save one turkey vulture, but now I saw feathery movement on the roadside and birds that headed for the bushes and looked like towhees. There wasn't time to get a good enough look to identify them. A big bushy-tailed rock ground squirrel darted in front of my truck and I ran clean over him; I didn't dare swerve enough to avoid him. I looked in my rear view mirror and he was gone. Evidently the tires had missed him and he got nothing worse than the fright of his life.

From Sonoita, Arizona I got on 82 south to Patagonia and arrived in town a short time later. I was surprised at how easy the trip had been. Wrong Way Tom had made it without a hitch. A sign directed me to the Stage Stop Inn and I parked out front and went inside where I had to ding the bell to rouse the clerk. She was Hispanic and young and told me that the restaurant closed at nine and opened at seven. Shoot, I thought. No coffee for breakfast; I had to be down the road at the preserve at seven sharp. I should have brought my own coffee-making gear.

Outside the hotel, barn swallows were everywhere. I looked at them through my binoculars and then went back to the room. It was after five and instead of walking around and doing any bird watching I decided to check out the Lounge. I figured there would be bird watching galore tomorrow. Besides, it was Miller time.

The bartender told me that there were some one-thousand people in the surrounding area and that they didn't often show up at the Stage Stop Lounge. The lounge, he says, was for the convenience of the hotel patrons, but a lot of them were bird watchers and they didn't drink much. "Just a few GT's occasionally." I asked him what a GT was and learned that it was a gin and tonic.

"You sell much of that Bacardi 151, here?" I asked him.

"I won't mix drinks with it," he replied. "It's too dangerous. I just use it for flaming drinks."

I downed the rest of my beer.

"Hey," he said. "Let me make you a flaming Dr. Pepper."He got a short, none-too-clean glass -- like a cafeteria milk glass -- and pumped it full of low grade beer from the tap. Then he filled a shot glass with root beer schnapps and set the two in front of me. From the bottle of Bacardi 151 he poured the tiniest bit of high test rum on top of the schnapps and set it on fire. The flame burned weakly. "Drop the shot in the beer!" he ordered.

I picked up the shot of flaming schnapps and dropped it in. There was a ploop! and beer cascaded over the rim of the glass; I knew it would. The glass was too full.

"It's supposed to spill," he told me, though he didn't offer any good reason why. Properly mixed and scorched, this drink was supposed to taste like Dr. Pepper.

I drank what was left in the glass. The beer was warm and flat and the rum had spilled out and I realized that root beer schnapps didn't go with beer on the best day it ever had. Not only was it the dumbest drink I ever had, but it tasted awful as well.

"Yum," I said.

I chatted with the bartender a bit longer. He made references to people with grudges against each other around these parts. He also said he knew how to bring business to this lounge but implied that there were forces at work against him. Patagonia: scenic, peaceful, quiet ....but with a terrible secret. I thought.

I turned to the bar TV and saw a show with a DJ playing recorded music for a bunch of dancing teens. I remarked that it was a shame that high school kids didn't have live bands at their dances. I said that in the 1960s we used to always have local bands from the various high schools who would audition to play at each dance and that we would have laughed ourselves sick at the thought of some DJ up there flipping records for us.

The bartender (so contraire!) explained that it was easy to become a second-rate DJ, but to be a good one took a lot of experience. I concurred and lamented that the same was true of professional wrestlers, psychics, and chiropractors, but then it was time to go. The bartender said that the Wagon Wheel was the place to be tonight and that it was just down the road, so off I went.

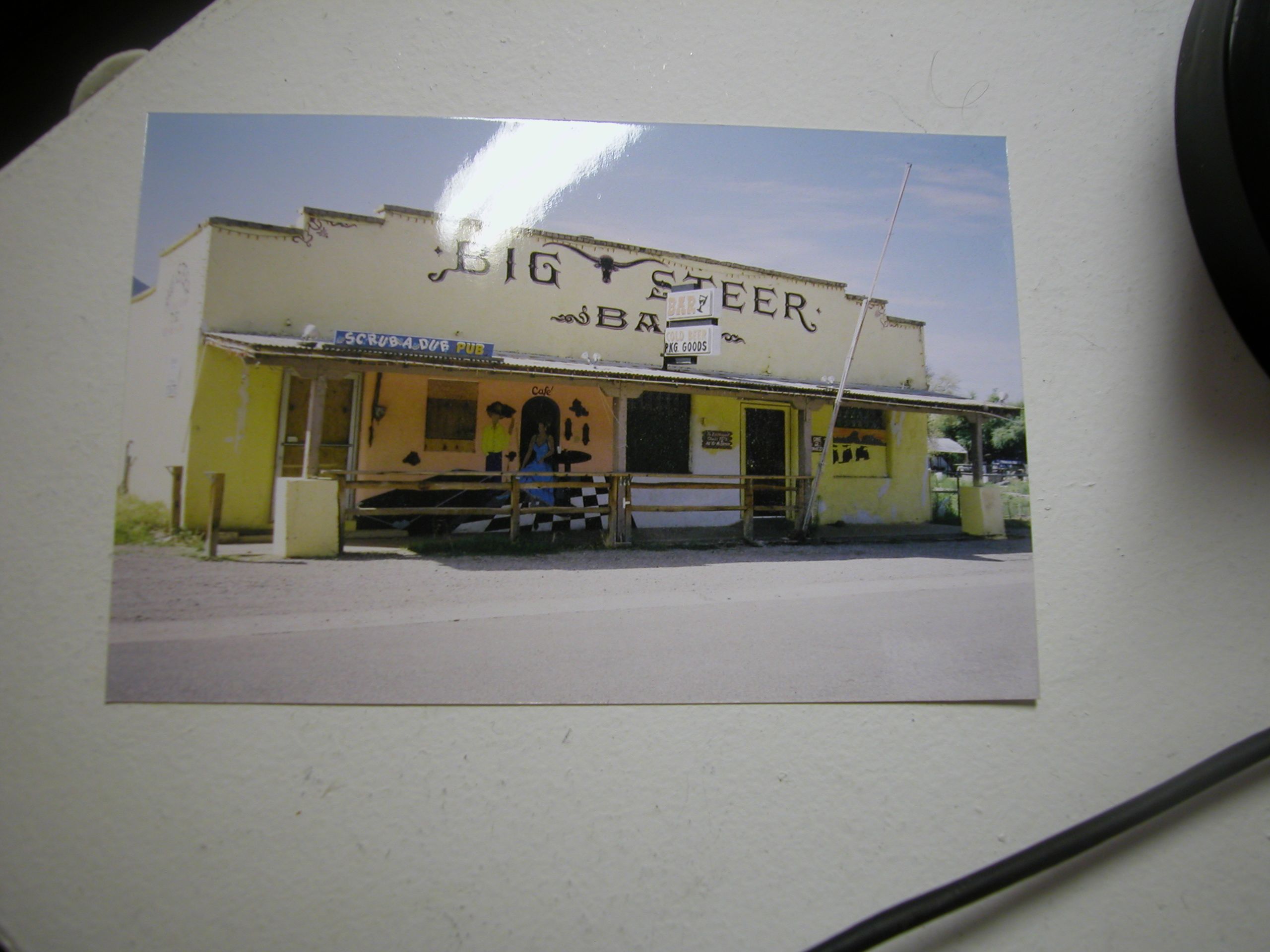

Outside, a big cool breeze was blowing. The weather was quite a bit nicer here than in Chandler. There was a grass-bordered sidewalk through a kind of park and to the left an establishment called "The Big Steer Bar." I walked over and looked in. It was kind of a rough joint, but I pushed open the door and stepped inside anyway and took a seat at the bar.

big steer bar.jpg

This bar no longer exists. There's another building here

and Jeff played piano there at least once.

big steer bar2.jpg

There was an older Hispanic guy in there with a cowboy hat and a bunch of guys with tape measures on their belts. A Springer spaniel lay on the floor. He looked up and checked me out, staring at me for five or six seconds before lying back down to sleep. The barmaid, in her forties, was wearing a long skirt, a tie-dyed shirt, and a concho belt. I ordered a Pacifico and she brought it to me with two dried-up wedges of lime. I guess tradition in Patagonia called for lime with each Pacifico, the way it used to always be with Tecate in Mexico.

There was an Anglo couple in the bar in their forties and they announced that they had been in love for nineteen years and were finally getting hitched. The Hispanic guy came over and embraced them both.

The TV above the bar blared with a show about some black city kids raising domestic pigeons called flights. They were waging "pigeon wars," a sport where you send your flock of pigeons out to lure the other guy's birds back to your coop. When you've got his birds in your coop, you hold them for ransom. I watched for a while until the beer was gone and then I left for the Wagon Wheel.

Wagon Wheel Saloon Patagonia Arizona 2002.jpg

The bartender at the Stage Stop Lounge was right; the Wagon Wheel was the place to be. It was full of people but I managed to get a good place at the bar. A girl was setting up a karaoke machine and I quickly went over and signed my name with the number of the tune I wanted to sing: "Mack the Knife." A few people got ahead of me.

Back at the bar I sipped a beer and looked the joint over. The bar itself was made entirely of varnished pine. The walls and ceiling of the room were covered with harnesses and saddles and old rifles and flintlocks and stuffed animals. There was a Red-Tailed Hawk posed as if attacking its prey, a few hapless deer staring from the wall, a gigantic elk's head, a pheasant, a ram, a ferret -- I counted ten animals in all.

The crowd was a mix of Hispanic, Native American, and Anglo and they were aged 21 to 81 I guessed. The couple next to me were getting on in years. They both sat drinking beer and chain-smoking. The man had a mottled, almost piebald complexion and thick head of gray hair with that yellow tinge some older guys get. The woman, his wife I presumed, -- to whom he rarely spoke -- was wrinkled and bony with age.

To my right were two younger guys. One had a good-natured smile and wore one of those cowboy hats that seems kind of broken in the middle so that rain would pour off of it front and back without even getting the guy's shirt wet. The other guy was odd-looking and short. He didn't look too swift to state it bluntly. He too wore a cowboy hat, and it had little guitar pins on it -- you know, those tiny pewter replicas of guitars. On his belt he wore a pretty wicked-looking knife. "I love Tucson," I heard him tell his friend. "But I can't afford to live there."

In all, the people reminded me of the clientele in the Vine at Rural and Apache in Tempe. Slightly weird-looking. But why not? This whole place was a little weird; full of stuffed critters and cowboy tack. There was a frog in the urinal too -- a plastic one, of course. I supposed it was there to keep things fun and interesting and make sure everyone was on the mark so to speak. The guys at the bar laughed about the frog. "Well," one of them said as he slid off of the bar stool. "I guess I'll go visit Mr. Frog."

"Give him my warmest regards," I said.

The karaoke started and several people did their songs before it was my turn. Normally shy, I had no fear of singing in front of this drunken crowd. My only worry was that they didn't have the original Bobby Darin version of "Mack the Knife" on the machine. There was another version floating around karaoke circles and it didn't sound even half as good. Luckily, this time they had the good one.

The song changes key at least three times but it is just a great number to choose for karaoke. You can even sing it like Satchmo if you like and aside from the key changes and the four-measure note you have to hold at the end, it is very forgiving. I did a real good job and got a fine applause. In fact, a couple of people came out of their seats to shake my hand and punch me in the arm. It was Darin's arrangement actually; I'm not that hot a singer.

The guy in the cowboy hat next to me actually had a good voice, but he picked some countrified thing to sing. I complimented him on the job he did. The karaoke was all so jolly and everyone joined in; even the old guy next to me went up and sang.

Soon enough, however, I was ready to leave. I don't like staying up late. I had had my beer and sung my song, and now I was hungry, sick of tuna, and ready to cheat on the diet, but I realized it was 8:50 and the clerk at the hotel said the restaurant closed at nine. I'd never make it. I decided to have something to eat at the bar.

I ordered a Philly Cheese Steak Sandwich and fries, and oh, what a mountain of fries it was! Calorie city. I ate it all and didn't feel guilty because I hadn't had a real meal in more than a week so it was time. Let me say this: I love American food. The bars, pubs, cafes, and restaurants of America have it down to a science. The lowliest dive can provide a good tasty feed anywhere in this country. Try ordering something to eat in a similar cantina in Mexico. Barf!

It took me a while still to get out of the joint. There was but one barmaid for this whole mob and she had my credit card and it took her forever to get back to me so I could cash out. I finally paid up and split.

On the way back I passed the Big Steer Bar and noticed a fresco on the outside wall -- a painting of some floozy, drink in hand. Standing next to it was another floozy -- a real one-- a young thing all painted up and dressed in floozy clothes. She was with a normal-looking person, so perhaps she was in a play or advertising or something. I didn't ask. I got back to my room, did 30 sit-ups, and went to bed.

The phone rang at six o'clock. It was the wake-up call I had requested. I went over to the preserve, which was only a five-minute drive and saw a bunch of cars and ten or twelve people hanging around. We made some quick introductions and then the Nature Conservancy guy came over and gave us a little talk. Mostly he just told us about the relationship of the Conservancy with the townies and things like that. He also warned us of chiggers and to stay out of the tall grass.

We stood at the edge of a wide meadow just beyond which was a huge meandering stand of giant cottonwoods. Some of these trees were over 100 feet tall and very old.

A lark sparrow jumped into a scraggly bush a few feet in front of us, and beyond -- in the meadow -- Cassin's kingbirds flew back and forth between bushes and scags. We all looked at them hard, hoping there might be a rare thick-billed kingbird among them. A pair of hooded orioles scared the lark sparrow out of the bush and everyone's binoculars focused in on the brightly colored male.

Far across the field -- at the border of the woods -- a yellow-billed cuckoo sailed along and alighted in a tree. That bird was a new one for me, and I added its name to the list in my notebook just under the hooded oriole. Then I drew a five-pointed star next to it to show that it was a life lister.

There was a trail through the meadow leading into the cottonwoods, and our group slowly moved down it. Phainopeplas were everywhere and we talked about how even the most spectacular of birds becomes a "trash bird" if there are too many of them around. Such was the case with phainopeplas on this trip. You'd see movement in the trees and raise your binoculars to your eyes only to lower them with a disappointed frown and say, "Just a phainopepla." But the phainopepla is one of the most beautiful birds of all. For those who may be unfamiliar with them, imagine a lean cardinal dipped in the blackest of paint from crest to tail. Give him a narrow bill and two blood-red rubies for eyes. Then add a startling patch of white on each wing that appears only in flight, and you'll have an idea of what the bird looks like. More than once a person has seen my binoculars and come up excitedly to say, "We just saw this bird that looked like a black cardinal!"

"Phainopepla," I answer immediately.

Phainopeplas are silky flycatchers of the arid Southwest. At certain times of year they feed upon poisonous mistletoe berries. During these times, their stomachs shrink to the size of the berries and they process them one after another by swallowing them and squeezing the pulp and seeds out of their bellies and into the intestines and, rather quickly then, into the outside world again. Mistletoe berries don't have much nutritional value, so the birds have to eat an awful lot of them.

A curious drama plays out when the remains of the berries pass through the bird. Mistletoe berries are very sticky. (In fact, people used to use them to make birdlime.) When the sticky seeds that fall from the phainopepla adhere to the limbs of a mesquite tree, the tree knows it and starts a process of self defense by excreting a kind of sap under the seed that raises it above the bark. At the same time, the seed begins its attack by sending out a root-like shoot downward toward the surface of the limb. The tree raises the seed and the seed counterattacks by lengthening the shoot and the race is on. If it rains before the shoot reaches the bark, the seed is washed away and the tree wins the race. If not, the seed will root itself there and a parasitic clump of mistletoe will grow on the limb of the mesquite tree.

We saw yellow-breasted chats when we got into the woods and the occasional white-breasted nuthatch crawling upside down over and under the limbs high in the cottonwood trees. I was a little surprised to see the nuthatches there. I always felt that they were high-altitude birds.In a clearing overlooking the stream, I spotted a lazuli bunting and everyone rushed over to look. The lazuli bunting is always a welcome sight -- or at least the turquoise male is; the drab female is likely to go unnoticed. There were acorn woodpeckers and Gila woodpeckers, red-shafted flickers and summer tanagers in the woods. Hopping on the ground was a small bird with a dark spot on its breast. "Song sparrow," I announced.

"It's a Bewick's wren" someone said.

"But it has a spot on its breast," I protested.

"Well, then it's a Bewick's wren with a spot on its breast."

I looked again and had to admit it looked an awful lot like a Bewick's wren. But what was with the spot?

That wasn't the last misidentification I would make that day. A while later, we were at the edge of a clearing and someone shouted, "Gray Hawk!" I looked through my binocs and caught a gray bird in the field of view. "I've got him," I said as I watched the bird whirl in the intense, magnified blue of the clear sky."He's gone," I heard someone say.

"I've still got him!" I replied excitedly. A gray hawk was a rare bird after all.

"No you haven't."

I lowered my binoculars and saw that I had been looking at a big, bull goose Cassin's kingbird fluttering up there.

"Oops," I said.The trail ended at another stream overlook. There we spotted a blue grosbeak and another male lazuli bunting. We got a warbling vireo there too, although I felt it looked a little chubby for one and I never saw the characteristic white eye line. I wrote him down on my list anyway.

We all sat on some logs and loafed a bit. One of the guys was an former US Air Force F-15 pilot and he and another guy talked about birds and planes. The girl in front of me had a pair of Swarovski 10 X 42 roof prisms and she let me try them out. I focused on a tree that had fallen across the stream. Through the binoculars, the tree looked huge and the view was brighter than that of my Swift Audubon 8.5 X 44 porros. These binocs had some fine optics. Just the same, the image shook quite a lot and the field of view was only 350 feet or something -- too narrow for my taste.

Let me clarify the above with some pertinent facts about binoculars. The "10" in "10 X 42" is the power of the binoculars. Simply stated, a pair of ten-power binoculars make a bird look ten times as big as he is. The "42" is simply the diameter in millimeters of the objective lenses -- you know, the big end of the binoculars. The bigger this number, the larger the lenses and the more light collected. The term "roof prism" refers to how the light is sent through the binoculars. I have no idea what goes on inside, but there are basically two types of binocs: roof prisms and porros. The position of the prisms in porros imposes the standard binocular shape we are all so accustomed to seeing. The placement of the prisms in roof prism binocs, however, results in quite a different shape, and it allows the user to look straight through the binoculars without the offset eyepieces of the familiar-looking porro glasses. Imagine taping two toilet paper tubes together and looking through them and you'll get the idea of how roof prism binoculars are shaped.

A lot of people think that the higher the power, the better the binoculars. This is simply untrue. Bird watchers are the best experts in binoculars and they almost always use from seven to ten power -- rarely lower and almost never higher. Eight power is ideal in my opinion. If you get beyond ten, you'll begin to need a tripod to steady the image. The birds will seem to jump around so much through those glasses that you'll have real trouble identifying them. Look at it this way:

Imagine you've got a 40-power telescope on a tripod precariously focused on a distant star and a pair of hand-held seven-power binoculars. Look at the star with the binoculars for a while and then take the telescope off of the tripod, hold it in your hands, and try to do the same. Which device do you think will give you a quicker, clearer, easier look at the star? You guessed it. Bigger ain't better.

The difference between ten-power and eight-power, while quite noticeable, will probably never make the difference in whether or not you can identify a bird. Lots of people love ten power, however, because of the satisfying, almost addictive size of the image. But they pay a price for that -- and not just in a more wobbly, jumpier image; they sacrifice field of view.

My swift Audubon 8.5 X 44s have a whopping 430-foot field of view. This means that at 1000 yards, I can see 430 feet left and right -- as well as up and down. It also means that I have an easier view; it's easy to get a bird in my sights with 430 feet to work with. Locating birds with a narrower field of view takes more effort and your eye and mind get tired faster trying to do so.

If you plan to buy binoculars, there's another thing to be aware of. After about 250 dollars you are not necessarily getting better optics; the difference between my 300-dollar glasses and a pair of 800-dollar nitrogen-purged roof prisms is almost all in weather proofing and shock resistance. The actual optics in my binoculars are virtually unmatched at any price.

Of course, there are other features that might be included in the 800-dollar package -- like close focus. I can only focus if something is at least 13 feet away, but my friend Nancy has expensive roof prisms and they allow her a close focus of just six feet. This is great if you're a butterfly watcher, or if you're very tall and a bird lands on your shoe, or if there are towhees hopping around under the bushes a few feet away. A close view can be spectacular, but there's got to be a price for it; you'll sacrifice something -- field of view -- whatever. There's always a trade-off with any special binocular feature.

Most people don't realize what a tremendous difference good binoculars make. I didn't know that myself until I upgraded to my Swift Audubons. I can't even see through my old binoculars now. How I ever used them I'll never know. So, if you want to take up bird watching, get some good birding binocs -- and don't ask some hunter in the sporting goods section of WalMart or Popular Surplus for advice. They don't know diddle about binoculars. Ask some bird watchers. Over the past sixty years they have put more demands on optics than anyone else on earth and are the real reason that binoculars have evolved into the quality instruments that they have.

Three final suggestions: 1.) Don't buy any binoculars with the little rocker arms that you focus with. If they were a good idea, you'd see them on the 1500-dollar models, but you don't. 2.) Don't buy any instant focus binoculars unless you are so gullible that you believe in magic wands and fairy godmothers. 3.) Don't buy any binoculars with a zoom. You're not going to make a movie; you're going to go bird watching for Christ's sake, so pick a power from seven to ten like I told you and forget about a zoom.

There were a few things that were unsatisfactory about this bird walk. One was that it took us a solid three hours to hike a quarter of a mile into the woods. We spent five hours in essentially the same place and I had no idea that we would do that or else I would have brought some water with me. I had anticipated marching into the riparian area, knocking off some birds and then marching out in a half hour or so to caravan in our cars to the next birding area. That didn't happen. Instead we lounged around for five long hours and only then went somewhere else -- to the humming bird feeders in a private residence a minute or two drive from the preserve.

The people who owned the house charged nothing for the privilege of sitting in their yard. All they asked for was some "sugar money" donations so they could fill the feeders. I left them five bucks in the coffee can they had nailed to the fence.

It was all a nice set-up. There were ten big feeders with numbers on each so you could yell, "Violet-crowned on feeder four!" (Instead of "There's a violet-crowned on that half empty feeder sort of second from the end -- no... no -- the left end!" or something like that.) Hummingbirds swarmed around the feeders like bees.

We saw five species of hummers and I was happy to be reaquainted with the rufous hummingbird again. It was an old friend from my youth when I rouged cotton in the fields from Wickenburg to Safford. I have dates for him as far back as August of 1971. I didn't get to see the blue-throated hummingbird, however, which my computer tells me I had seen once on May 27, 1973, but I didn't mind; I had had enough bird watching for the day.

Despite the long trip, the bird list was pretty unimpressive and quite a bit disappointing. I had only a couple of life listers and the count for the day was a measley 39 listed here in taxonomic order:

1. Turkey Vulture

2. White-winged Dove

3. Mourning Dove

4. Yellow-billed Cuckoo

5. Broad-billed Hummingbird

6. Violet-crowned Hummingbird

7. Black-chinned Hummingbird

8. Anna's Hummingbird

9. Rufous Hummingbird

10. Acorn Woodpecker

11. Gila Woodpecker

12. Northern Flicker

13. Western Wood-Pewee

14. Black Phoebe

15. Vermilion Flycatcher

16. Ash-throated Flycatcher

17. Brown-crested Flycatcher

18. Cassin's Kingbird

19. Warbling Vireo

20. Barn Swallow

21. White-breasted Nuthatch

22. Bewick's Wren

23. Curve-billed Thrasher

24. Phainopepla

25. Yellow Warbler

26. Common Yellowthroat

27. Yellow-breasted Chat

28. Summer Tanager

29. Western Tanager

30. Lark Sparrow

31. Song Sparrow

32. Black-headed Grosbeak

33. Blue Grosbeak

34. Lazuli Bunting

35. Brown-headed Cowbird

36. Hooded Oriole

37. House Finch

38. Lesser Goldfinch

39. House SparrowWe had planned to go to a roadside rest area where people had seen the rose-throated becard, but I didn't bother. I knew the bird had not been seen this season and it was a waste of time. I bid everyone adiós and got in my truck and headed back to Chandler.

I passed Karchner Caverns State Park on the way, and I pulled in to take a look. All the tours were booked for the day, but I got a brochure and left. Then, a fear struck me and I turned back to the State Park and asked the ranger where I was.

"You've got a good hour back to Tucson," she said -- but I already knew what had happened. The State Park was right next to Benson and that meant I was thirty miles east of where I was supposed to be, a fact that translated as sixty miles of unnecessary driving. Dang!

Wrong Way Tom had done it again.

Go Back to OLD GEOCITIES Memoirs Page

GO TO THE NEW ESSAYS/MEMOIRS PAGE

HOME