5. Dos cuentos de

mi madre sobre canciones

Hace poco mi hermana dijo que creía que "Old

Black Joe" era una de las canciones más bellas

que nunca había sido escrita. Yo estaba de

acuerdo y al reflexionar sobre esto, dos cosas

se me ocurren. La primera es que cuando yo era

un niño mi madre me contó una historia sobre

como fue compuesta esa canción. La segunda

trata del autor de la canción, Stephen Foster.

Resulta que siempre he sentido lo mismo en

cuanto a otras dos canciones suyas: "My Old

Kentucky Home" y "Old Folks at Home" (Ya

sabes—"Swanee River.")

Weep no more, my

lady

No llores más mi dama

Oh, weep no more,

today

Oh, no llores más hoy

We will sing one

song

Cantaremos una canción

For my old Kentucky home De

mi vieja casa de Kentucky

For my old Kentucky home De

mi vieja casa de Kentucky

So far

away

Tan lejos de aquí

El puente de "Old Folks at Home" también evoca

una sensación de melancolía.

Todo el mundo está triste y sombrío

Cualquier lugar a donde vaya

Oh, negros cómo mi corazón se cansa

Lejos de los viejos en casa

A Foster le gustaba componer la letra de sus

canciones en la forma de hablar de los

esclavos del sur de Estados Unidos. El

personaje, el cantante de sus canciones por

regla general, es un esclavo—por lo menos el

oyente supone que sí y el dialecto típicamente

se escribe con "dis" en vez de "this,"

"de" en vez de "the," "wid" en vez de

"with" y así.

Foster, sin embargo, no usó esa forma de

hablar en "Old Black Joe".

Y pasaron los días en los que mi corazón era

joven y alegre,

Se han ido mis amigos de los campos de

algodón,

Ido del mundo a una mejor tierra que conozco,

Escucho sus suaves voces que llaman "Old Black

Joe".

En cualquier caso, la historia que me contó mi

madre fue que Foster solía rondar un

restaurante en el que el camarero negro, Joe,

siempre decía: "Sr. Foster, ¿cuándo va a

escribir una canción para mí, así tendré algo

que cantar cuando sirva a los comensales?"

Foster siempre respondía: "Oh, estoy en vías

de componértela, Joe".

Bueno, un día, según la historia, Foster

escuchó que Joe se estaba muriendo y fue a la

gran casa donde Joe era un sirviente. Encontró

a Joe en su cama muriendo.

—Nunca me escribió esa canción, señor Foster".

—Sí, sí, lo hice —respondió Foster. ¡Acabo de

terminarla!

Según la historia, colocaron un piano en la

recámara y Foster se sentó y cantó la canción

mientras la componía simultáneamente.

—Y así Joe murió feliz —concluyó mi madre.

La historia es probablemente una leyenda; no

la he encontrado en ninguna parte online de

todos modos. Sin embargo, encuentro en

Wikipedia: "El Joe ficticio de Foster fue

inspirado por un esclavo afroamericano en la

casa del suegro de Foster, el Dr. McDowell de

Pittsburgh", y eso en realidad confiere una

cierta veracidad al relato.

El título de este ensayo se refiere a dos

historias y la segunda es simplemente en forma

de una oración que mi madre dijo acerca de la

canción "My Buddy" de Gus Khan. "Oh, esa fue

una famosa canción homosexual de la Segunda

Guerra Mundial", dijo.

Gus Khan (nacido en 1886) escribió varias

canciones famosas y me consta que usted sabe

todas las siguientes:

"Dream a Little Dream of Me"

"It Had to Be You"

"I'll See You in My Dreams"

4Gus Khan

escribió solo la letra de "My Buddy." La

música fue compuesta por Walter Donaldson.

"Charlie My Boy"

"Ain't We Got Fun"

"Makin' Whoopee"

La canción "My Buddy", sin embargo, trata de

dos amigos en la Primera Guerra Mundial y no

en la Segunda. Uno de ellos fallece y el otro

lo extraña. Khan no tenía la intención de

decir que eran homosexuales (¡No es que haya

nada malo en eso!), sino simplemente amigos. A

pesar de esto, letras como "Echo de menos tu

voz, el toque de tu mano" tienen un

inconfundible sentimiento romántico. Y, por

casualidad, la palabra "gay" aparece en la

canción de 1922 mucho antes de que adquiriera

su significado moderno.

Amigos por todos los días gay,

Amigos cuando algo salía mal

Yo espero a través de estos días grises

Echando de menos tu sonrisa y tu canción

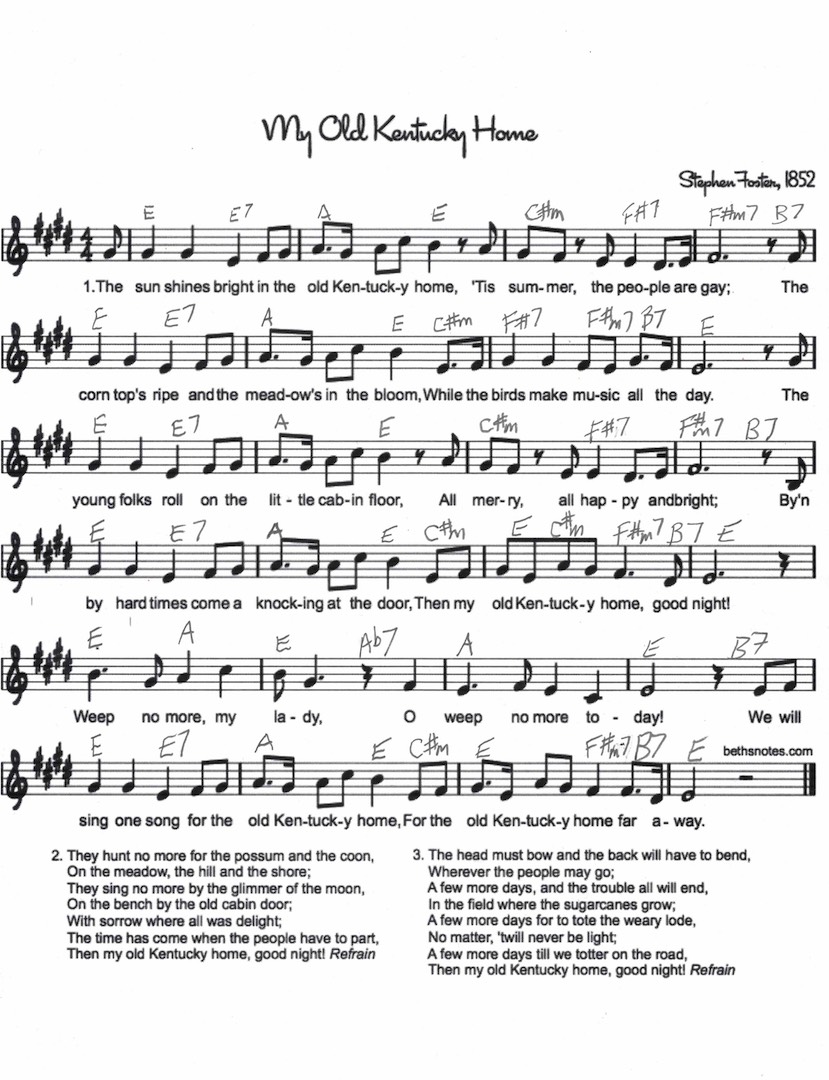

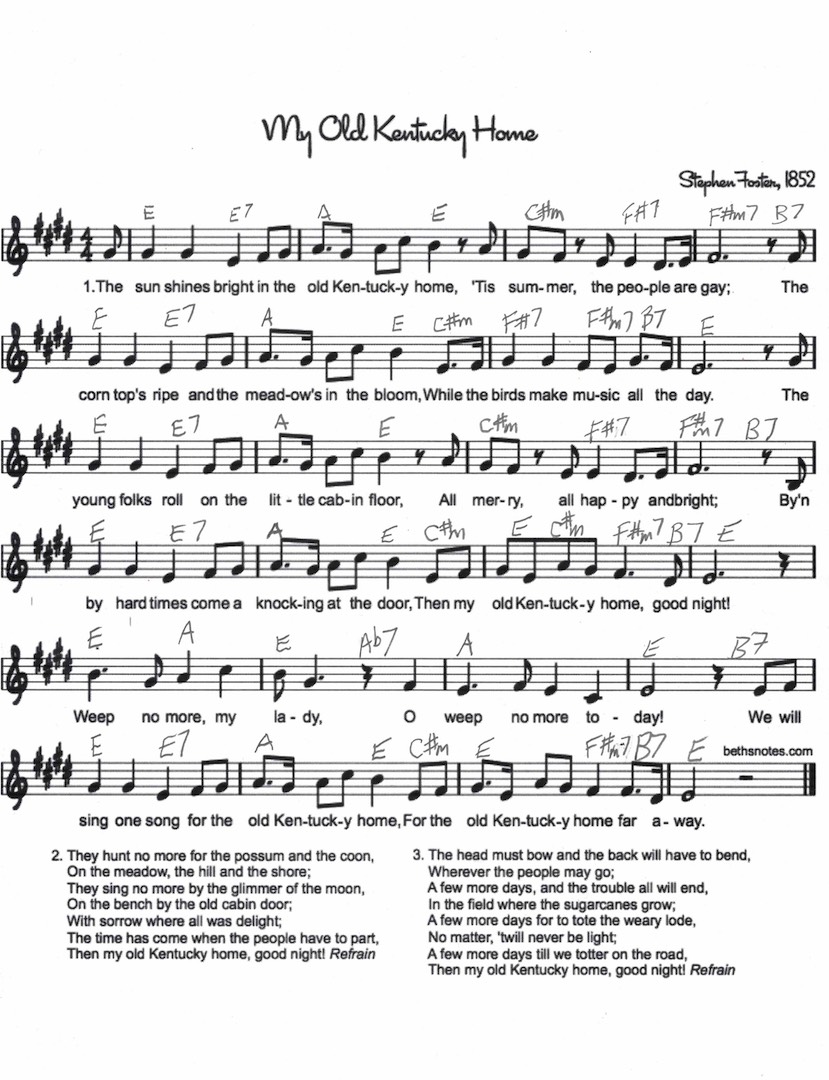

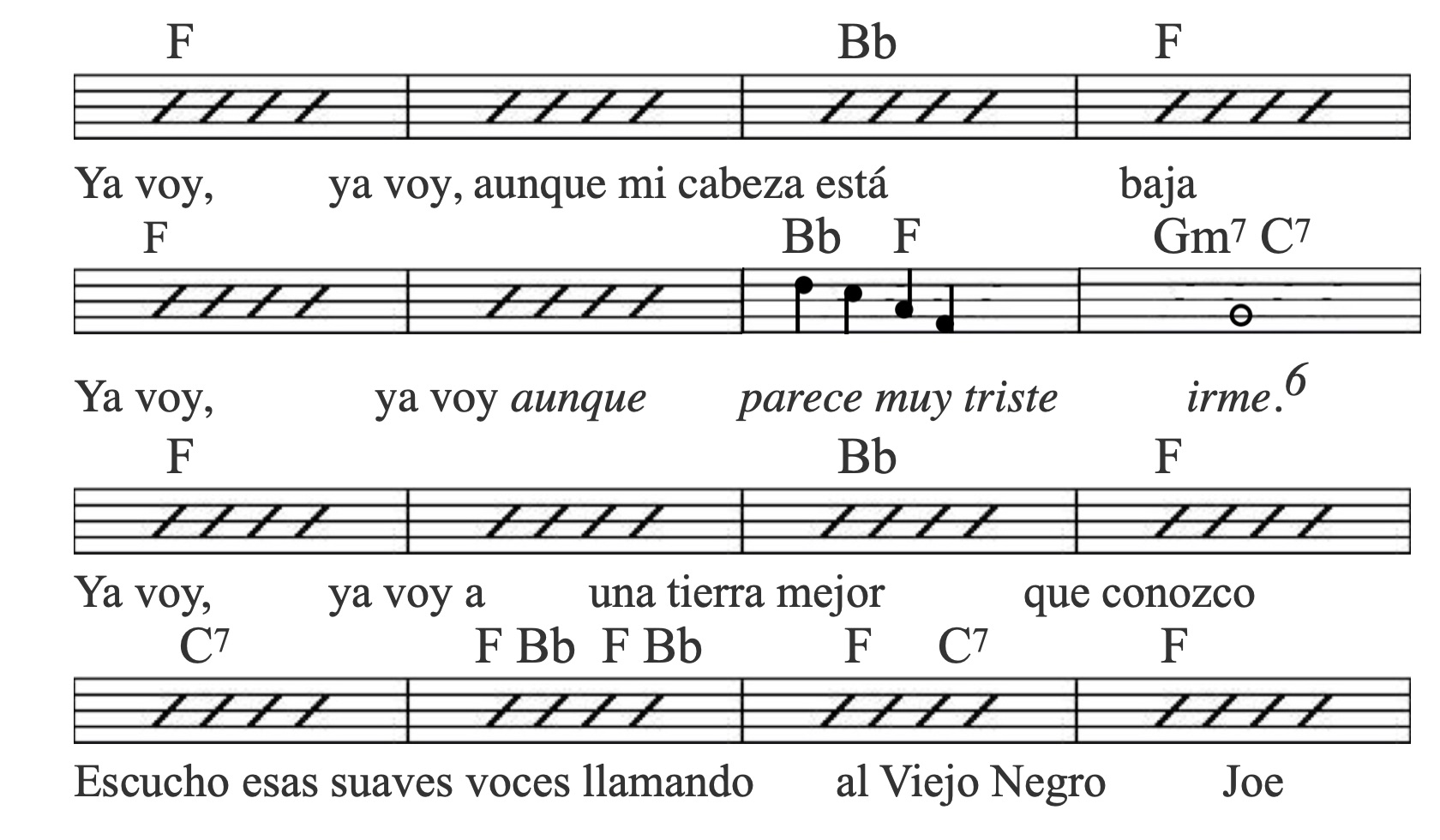

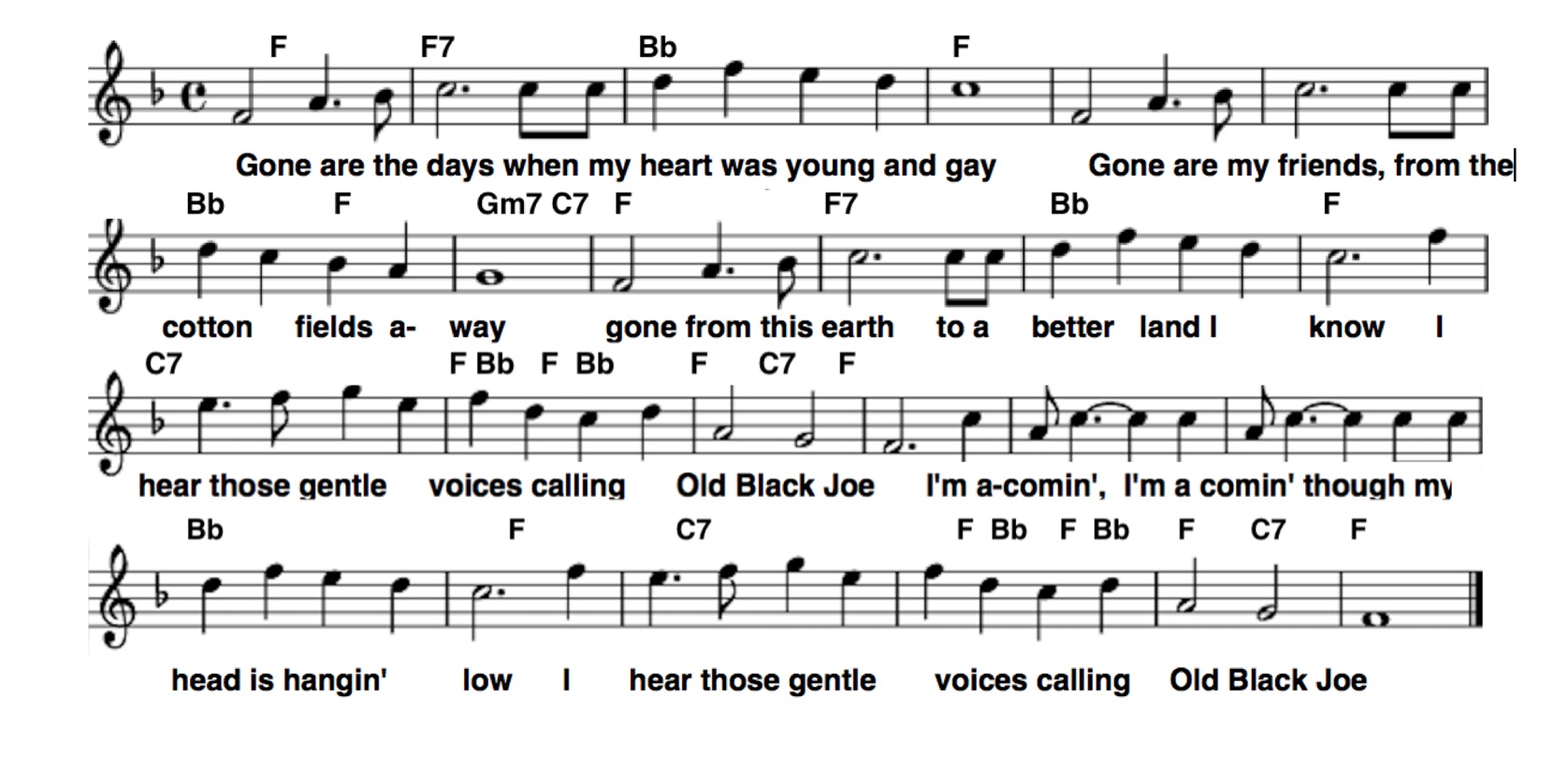

Ya que las tres canciones de Foster son de

dominio público, decidí incluir una. Para

sorpresa mía, al preparar la partitura, me di

cuenta de que yo siempre había cantado "Old

Black Joe" en mi propia manera. Espero que yo

no parezca demasiado atrevido al decir que

prefiero mi versión a la de Foster.

Verdaderamente creo que el estribillo es

demasiado corto. Termina de repente.

Así se canta la canción tradicionalmente:

Old Black Joe Spanish.jpg

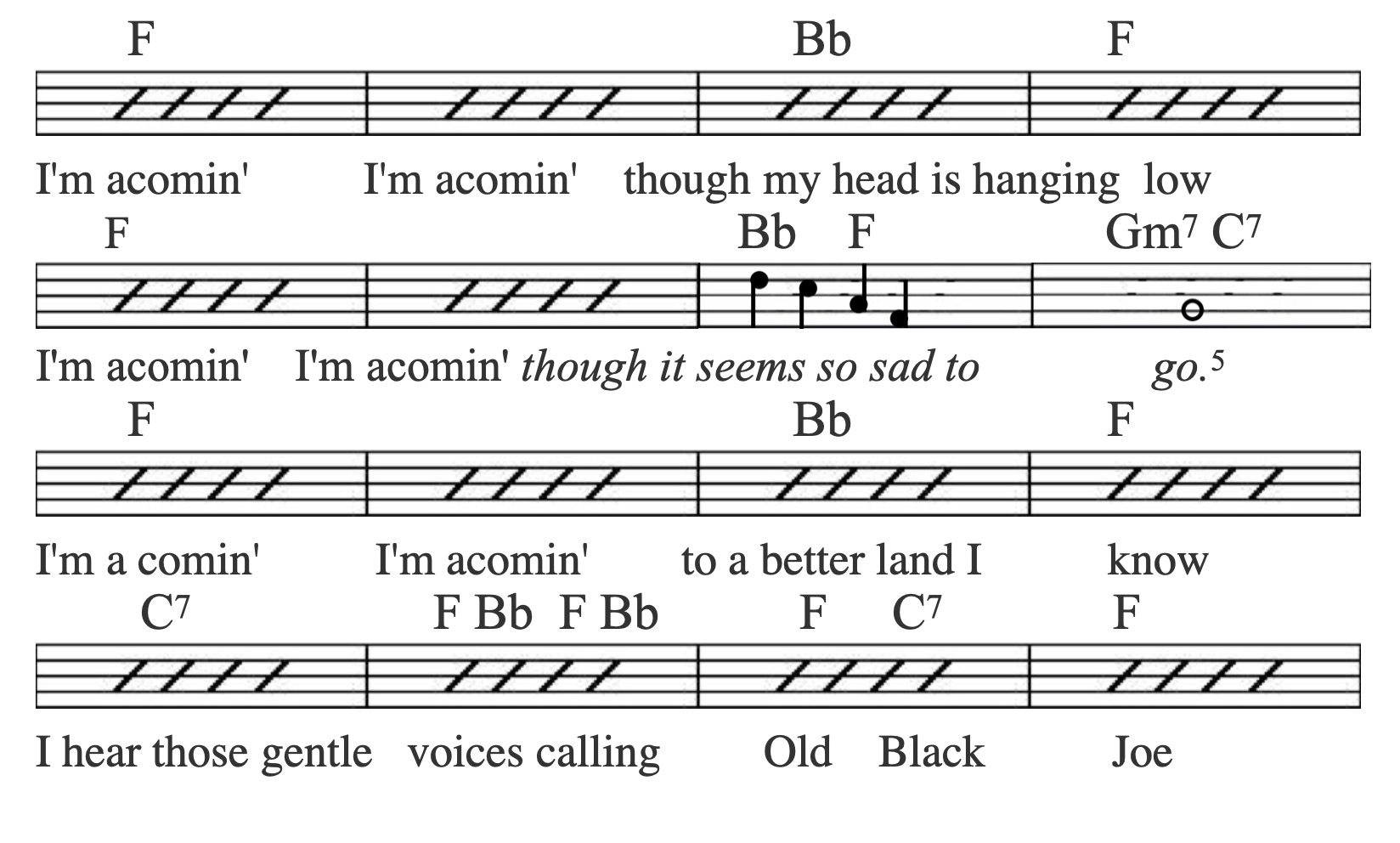

De niño, yo cantaba la canción con una letra

que aparentemente había compuesto y repetía la

primera linea del estribillo antes de

terminarlo con las palabras Escucho esas

suaves voces llamando al Viejo Negro Joe.

Opino que la canción verdaderamente necesita

estos dieciséis compases.

Yo cantaba la canción de niño así:

Old Black Joe How I Sing It.jpg

6 La letra

que inventé de niño está arriba en

cursiva. No muy buena pero suficiente.

|

5. Two of my Mom's Stories about Songs

Not long ago my sister said that she believed

that "Old Black Joe" was one of the most

beautiful songs that had ever been written. I

agreed and reflecting upon this now, two

things occur to me. The first is that when I

was a child, my mom told me a story about how

the song was composed. The second has to do

with the author of the song, Stephen Foster.

It happens by chance that I've always felt the

same way about two other Foster songs, "My Old

Kentucky Home" and "Old Folks at Home" (You

know, "Swanee River.")

Just before the Kentucky Derby begins, the

crowd sings "My Old Kentucky Home" and when

they get to the bridge and sing it, there

isn't a dry eye in the stands.

Weep no more, my lady

Oh, weep no more, today

We will sing one song for my old Kentucky home

For my old Kentucky home so far away

The bridge to "Old Folks at Home" evokes a

similar melancholy:

All the world is sad and dreary,

Everywhere I roam.

Oh, darkies, how my heart grows weary,

Far from the old folks at home

Foster liked to compose the lyrics of his

songs in the dialect of slaves in the southern

United States. The character, the singer of a

Foster song, as a rule, was a slave—or the

listener imagines so—and the dialect is

typically written with "dis" for "this," "de"

for "the," "wid" for "with," and so on.

Foster, however, didn't use dialect in "Old

Black Joe."

Gone are the days when my heart was young and

gay,

Gone are my friends from the cotton fields

away,

Gone from the earth to a better land I know,

I hear their gentle voices calling "Old Black

Joe."

Now, the story my mom told me was that Foster

used to frequent a certain restaurant whose

black waiter, Joe, would always say, "Mr.

Foster, when are you going to write a song for

me so I'll have something to sing when I wait

tables?"

Foster always replied, "Oh, I'm working on it,

Joe."

Well, one day, so the story goes, Foster heard

that Joe was dying and he went to the grand

house where Joe was a servant. He found Joe in

his bed dying.

"You never wrote that song for me, Mr.

Foster."

"Yes—yes, I did," Foster answered. "I just

finished it!"

According to the story, a piano was rolled

into the room and Foster sat at it and sang

the song as he simultaneously composed it.

"And so Joe died happy," my mom concluded.

The story is likely apocryphal; I haven't

found it anywhere online anyway. However, I do

find on Wikipedia: "Foster's fictional Joe was

inspired by an African American slave in the

home of Foster's father-in-law, Dr. McDowell

of Pittsburgh," and that actually lends some

plausibility to the tale.

The title of this essay mentions two stories

and the second one is simply in the form of a

sentence my mom said about Gus Khan's song "My

Buddy."

"Oh, that was a famous homosexual World War II

song," she said.

Gus Khan (born 1886) wrote a number of famous

songs and I'm pretty sure that you know all of

the following:

"Dream a Little Dream of Me"

"It Had to Be You"

"I'll See You in My Dreams"

"Charlie My Boy"

3Gus Khan wrote only

the lyrics to "My Buddy." The music was

composed by Walter Donaldson.

"Ain't We Got Fun"

"Makin' Whoopee"

The song "My Buddy," however, is about two

buddies in World War I and not World War II.

One of them gets killed and the other misses

him. It wasn't Khan's intention to say that

they were gay (Not that there's anything wrong

with that!) but simply buddies. Just the same,

lyrics like "Miss your voice, the touch of

your hand" have an unmistakably romantic feel

to them. And, coincidentally, the word "gay"

appears in the 1922 song long before it

acquired its modern meaning.

Buddies through all of the gay days,

Buddies when something went wrong,

I wait alone through the gray days.

Missing your smile and your song.

Since Foster's three songs are in the public

domain, I decided to include one of them here

and to my surprise, as I prepared the music, I

realized that I had always sung "Old Black

Joe" in my own way. I hope that I don't seem

too bold to say that I prefer my version to

Foster's. I really believe that the

bridge/chorus is too short. It ends too

soon—too abruptly. You can decide whether you

agree with me or not.

This is how the song is traditionally sung:

Old Black Joe English.jpg

As a child I sang the song with words that I

had apparently made up and I repeated the

first line of the chorus before ending with

the words, I hear those gentle voices

calling...

I think the song really needs these sixteen

measures.

Here's how I sang the song as a kid and still

do.

Old Black Joe How I Sing It 2.jpg

5The words I

made up as a child are in italics above.

Not too great, but they suffice.

|