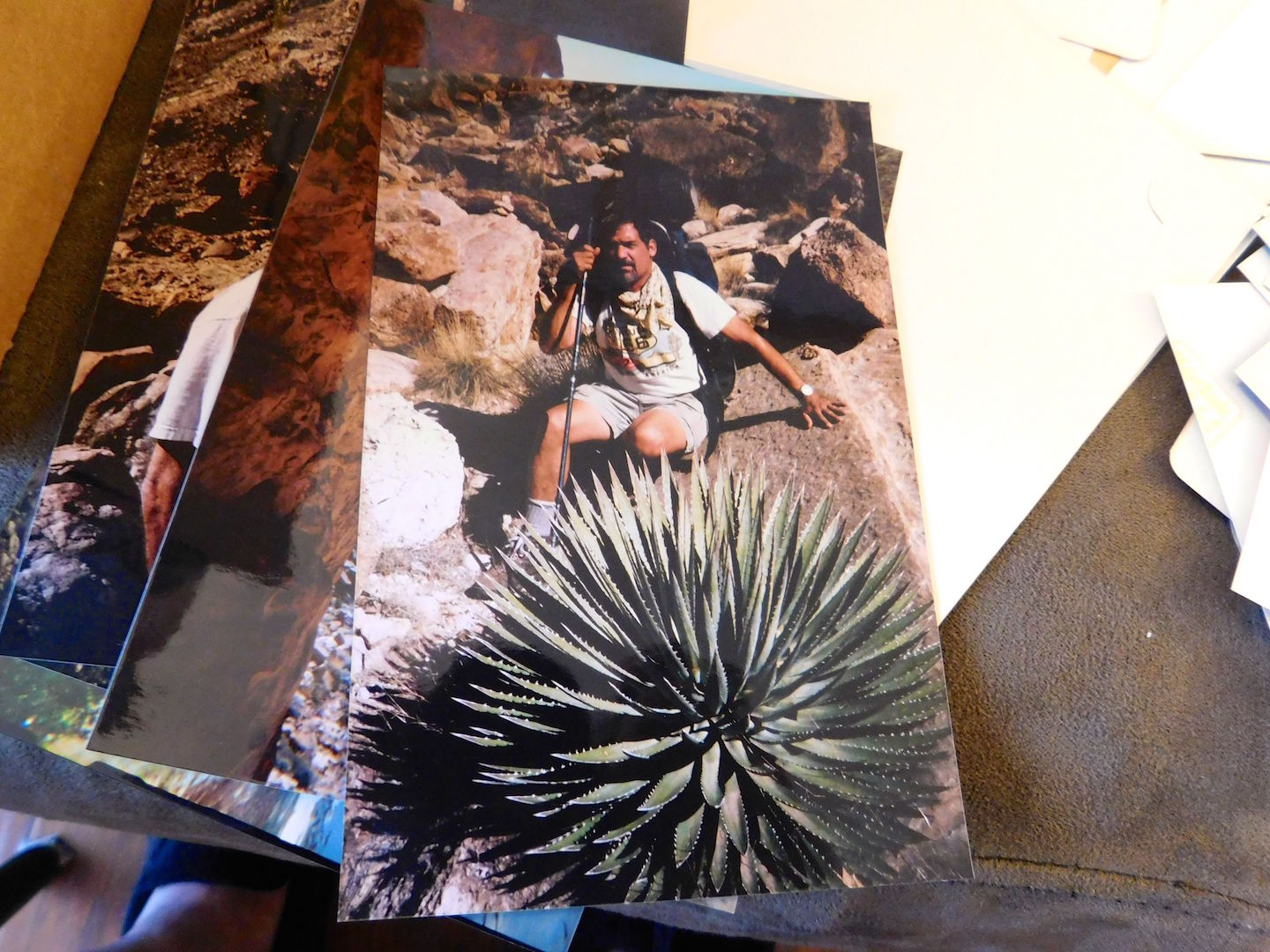

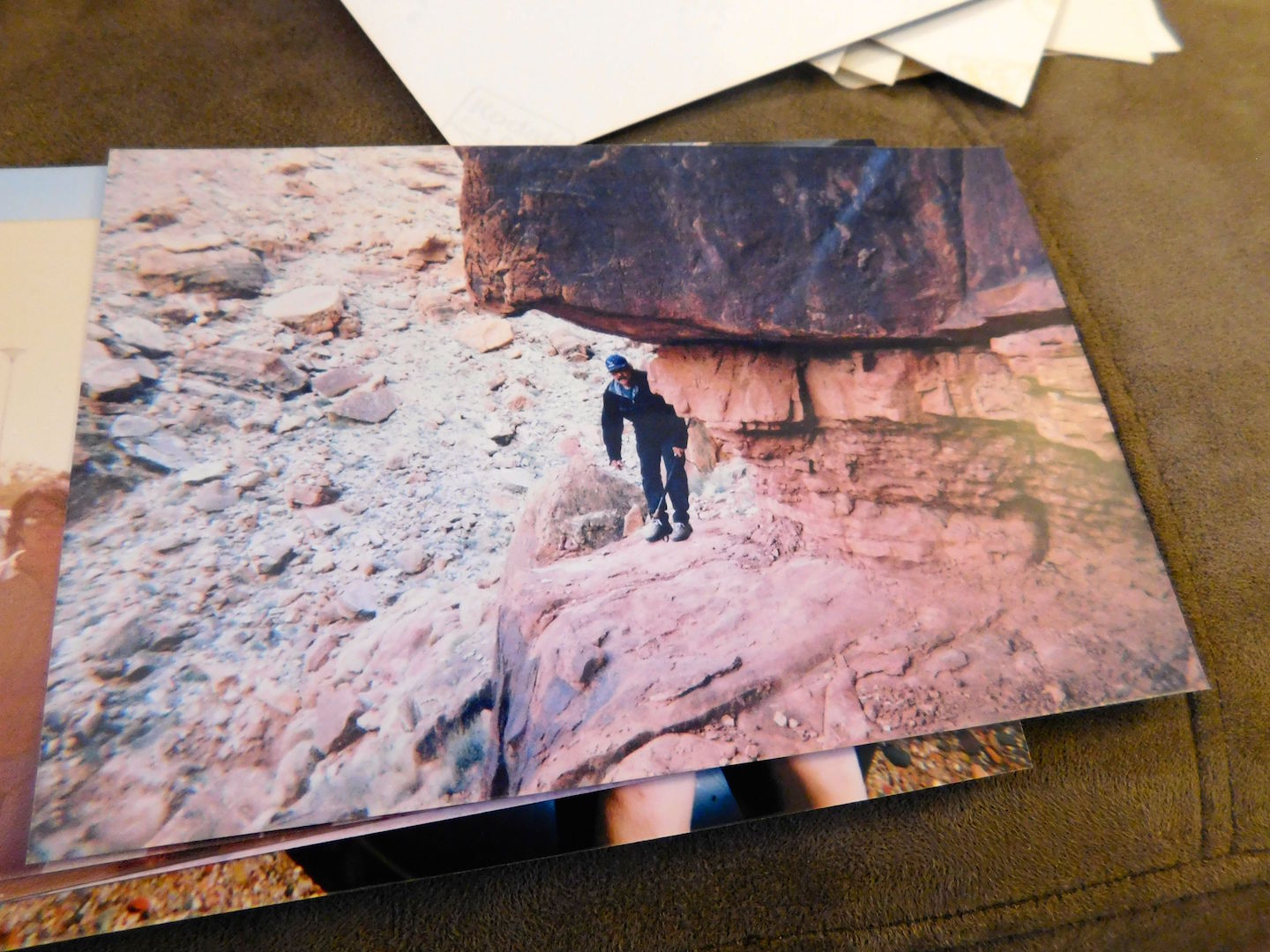

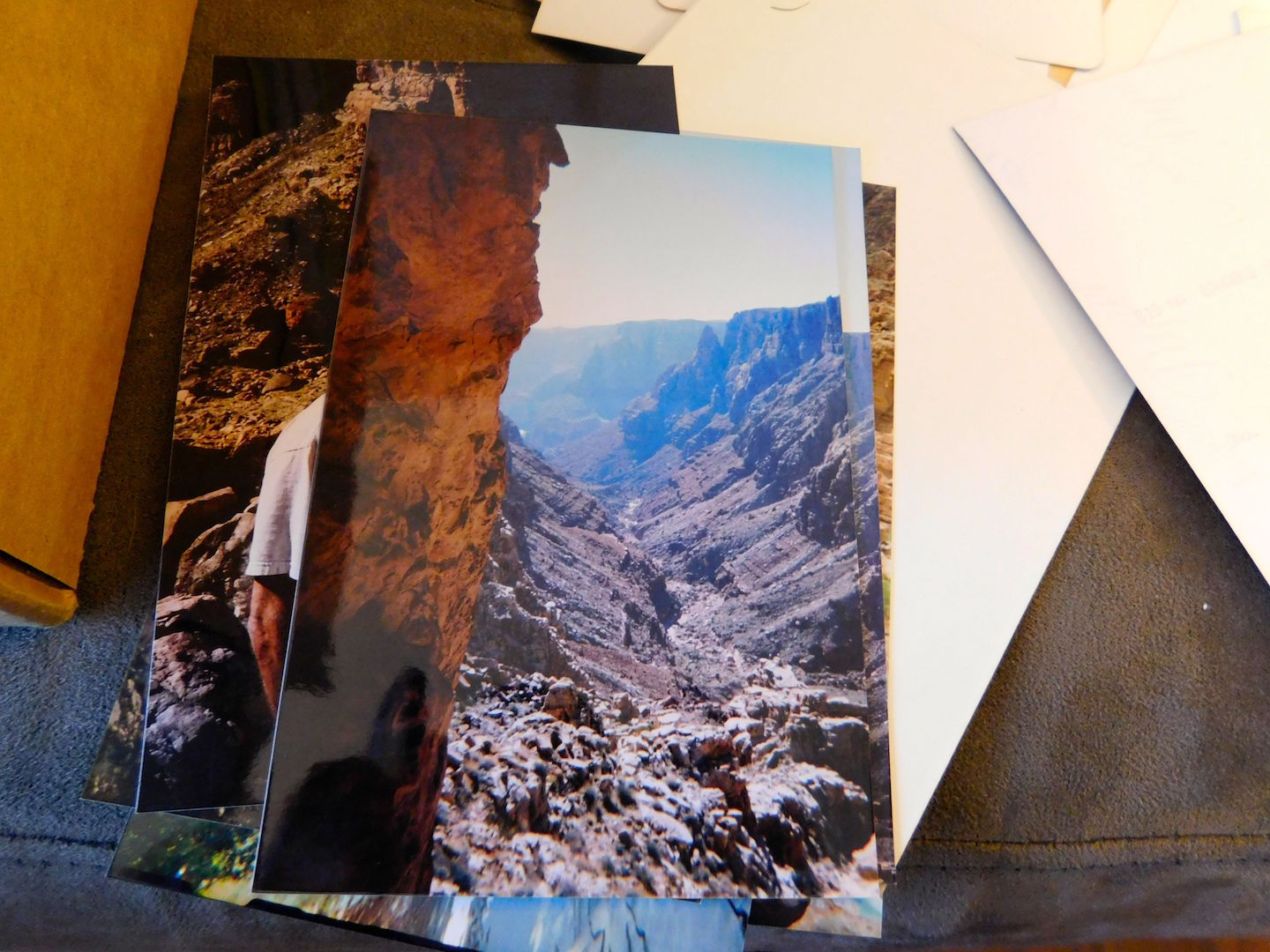

camp steve salt trail.jpg

Oops! Steve says the above

picture is the Little Colorado I think.

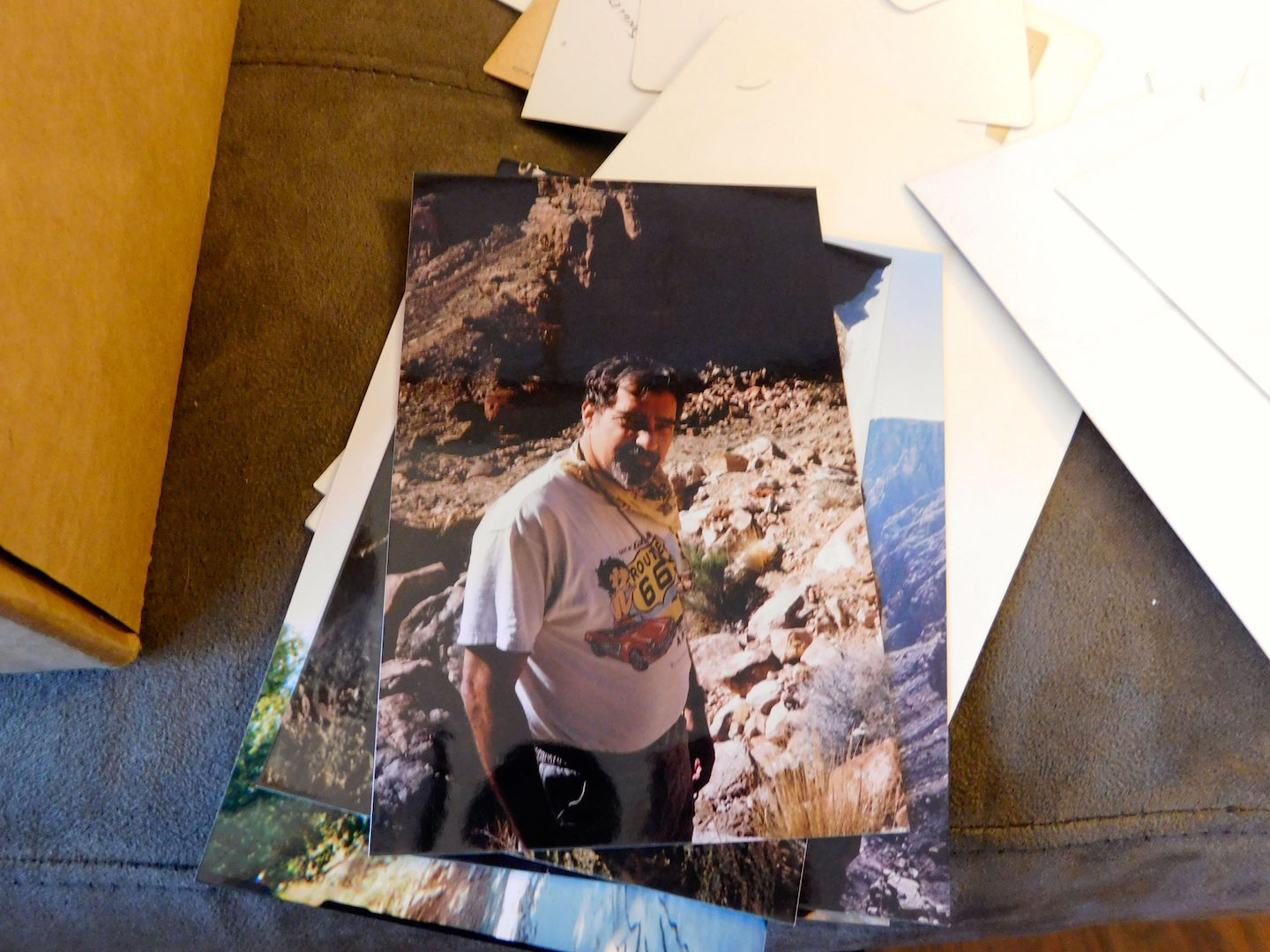

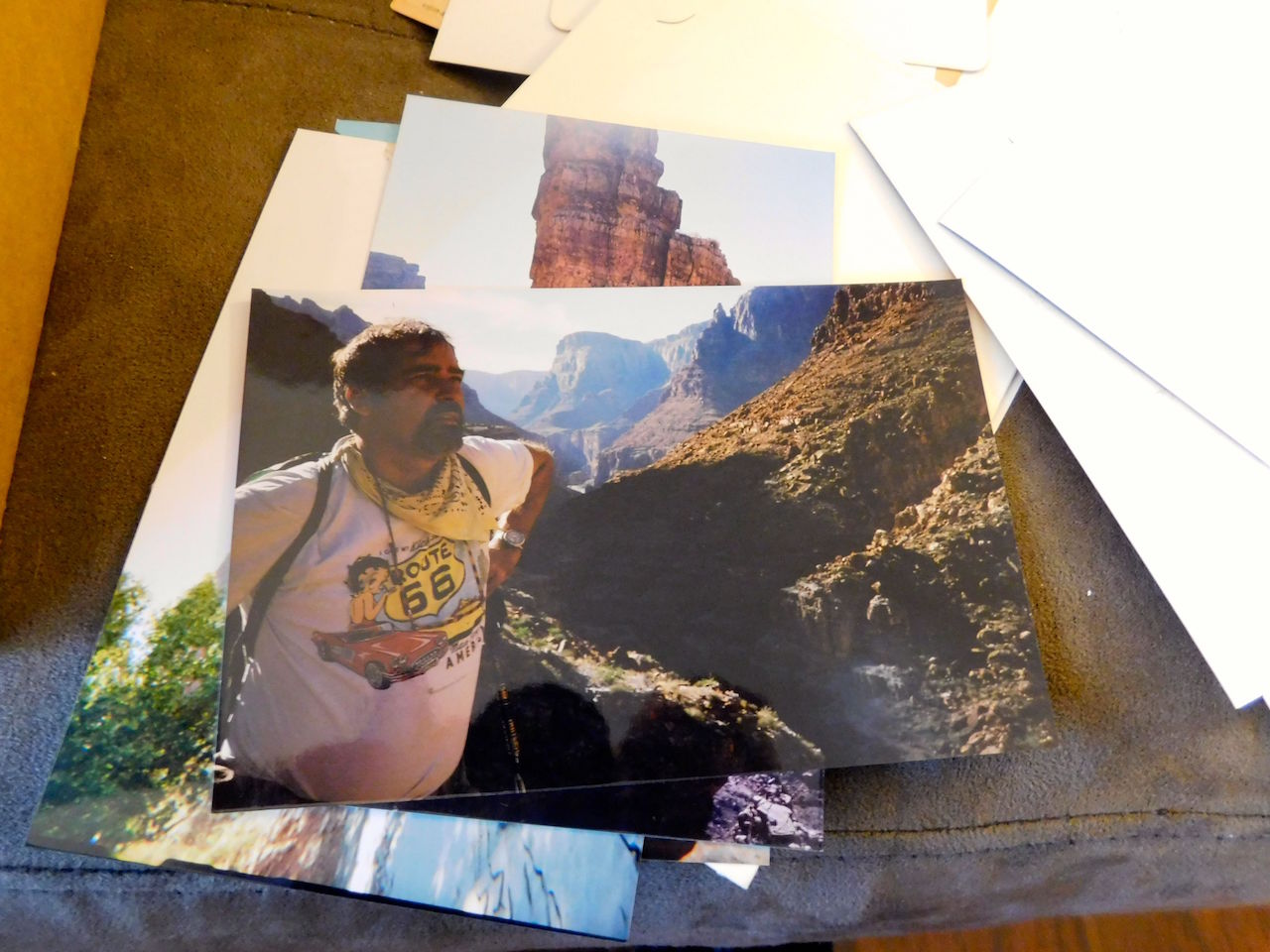

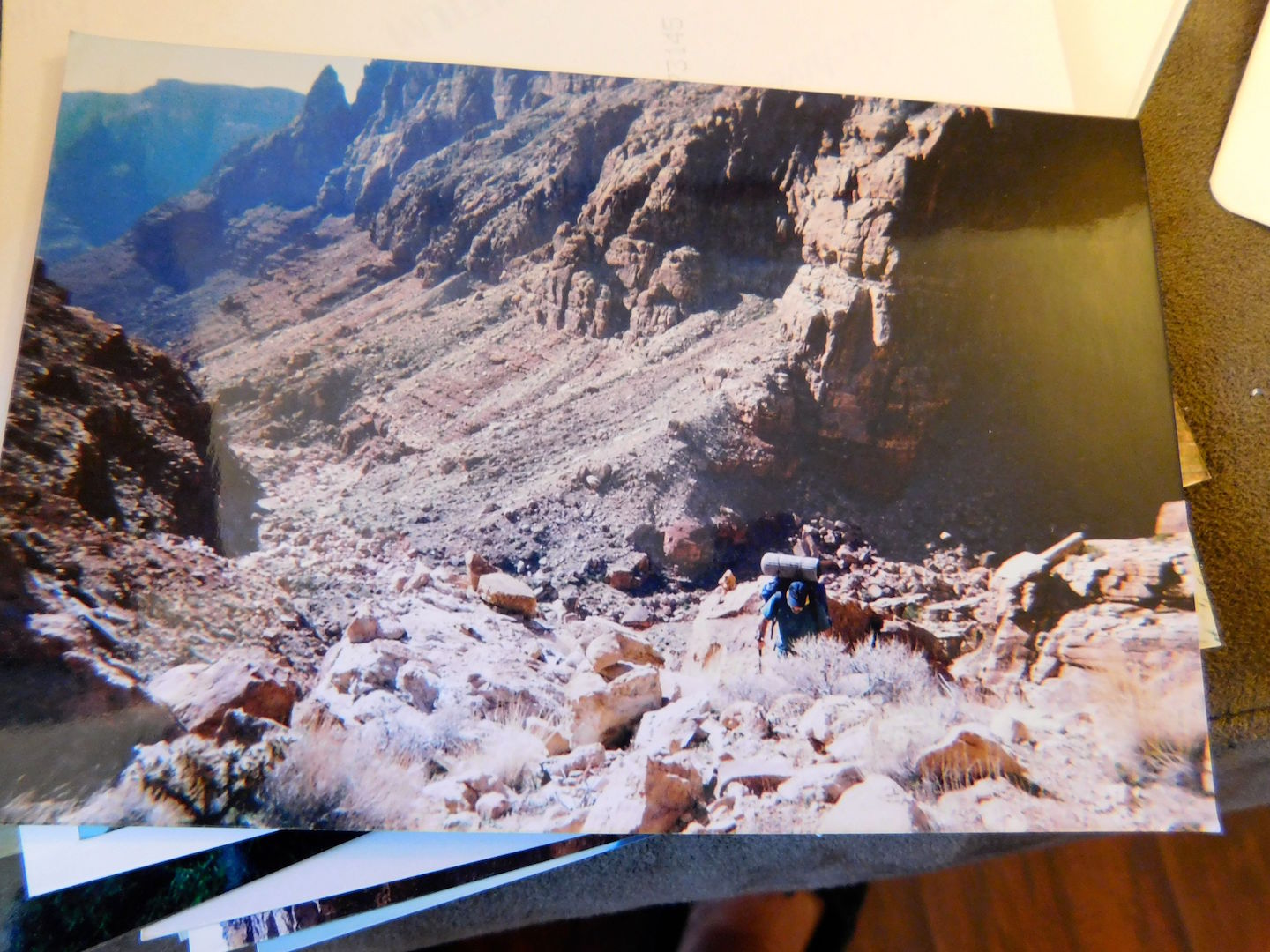

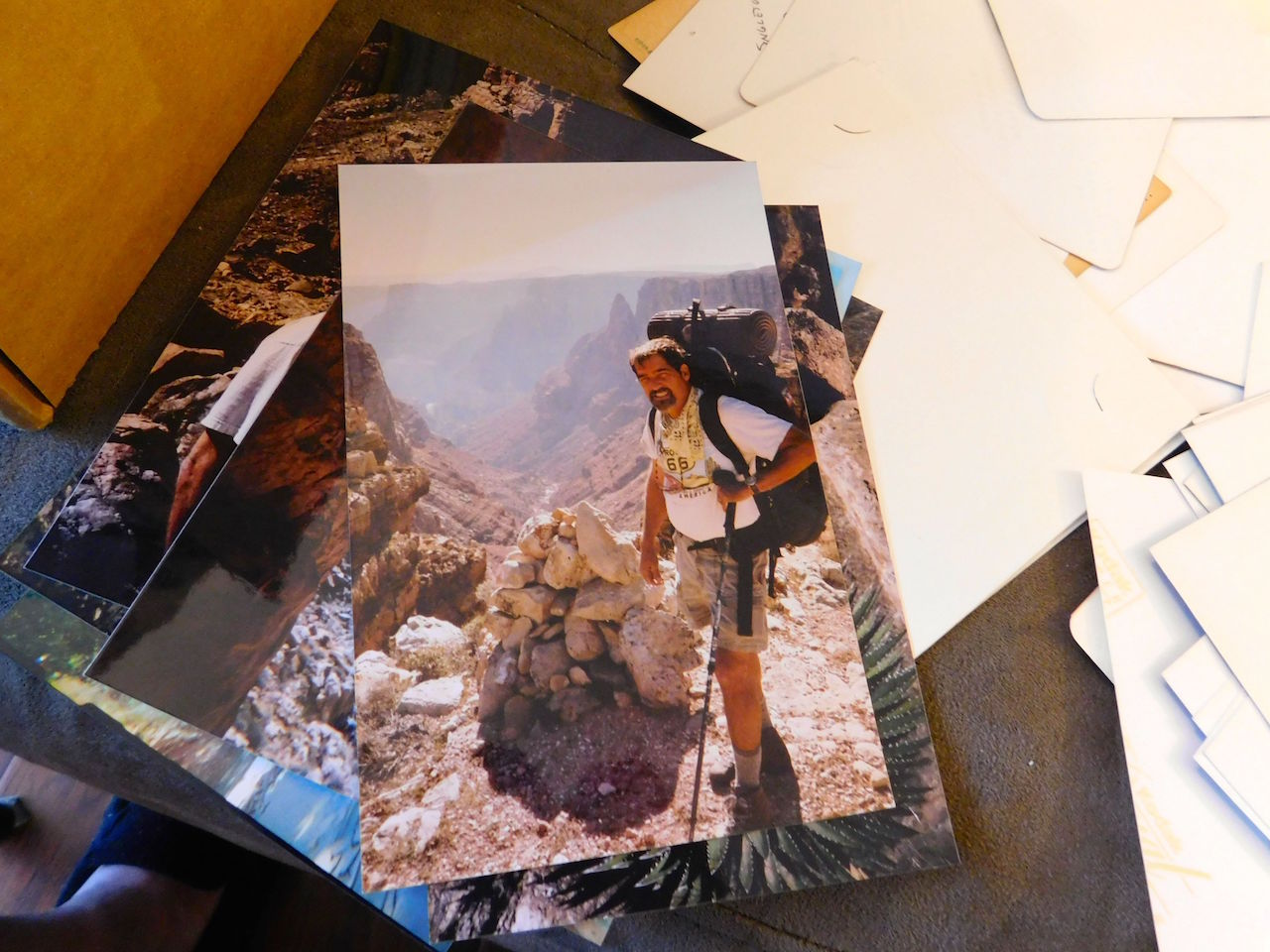

Salt Trail 2002 I think.jpg

Salt Trail 2002 v.jpg

Steve Salt Trail 2002 b.jpg

Steve Salt Trail 2002 c.jpg

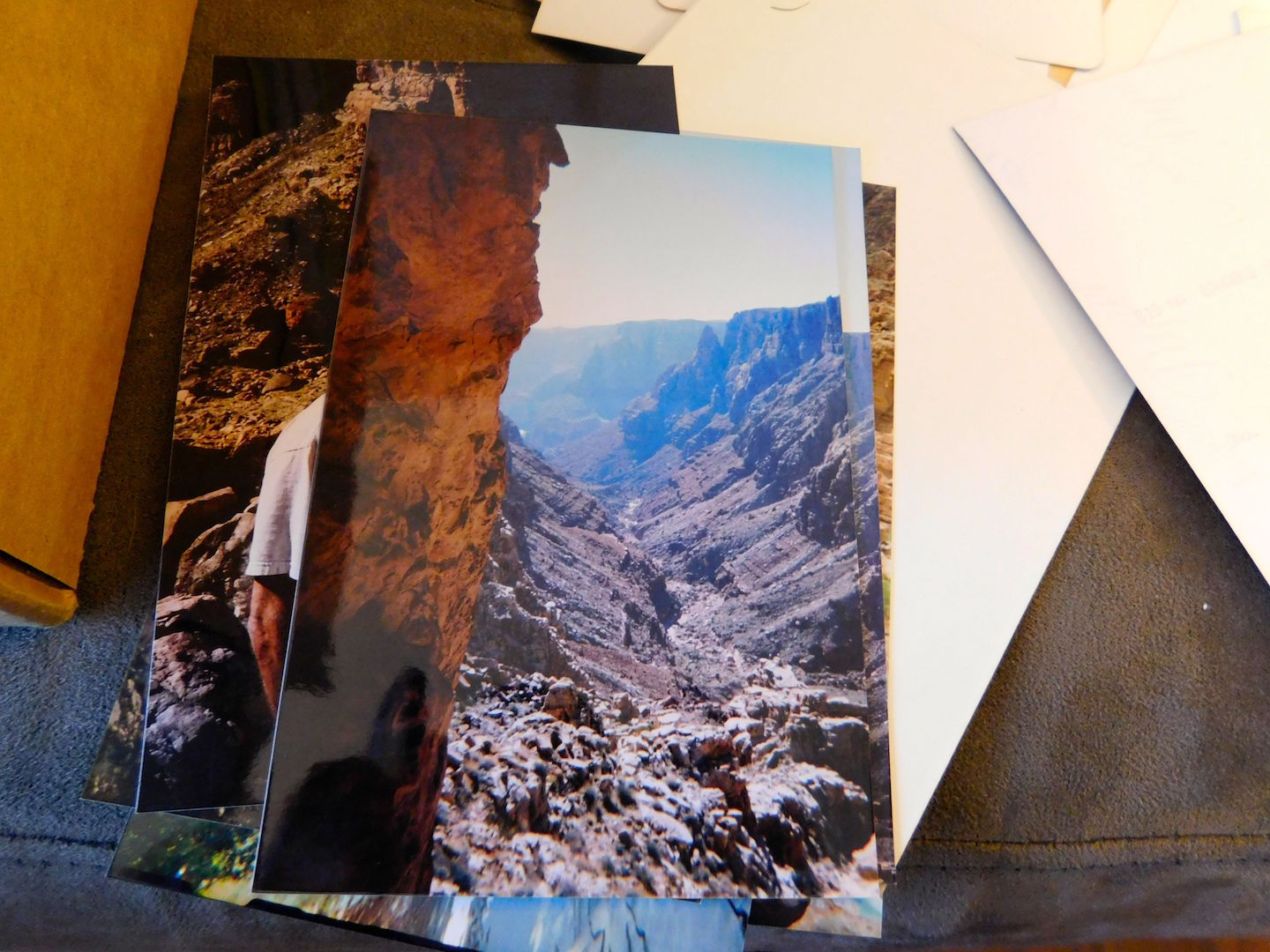

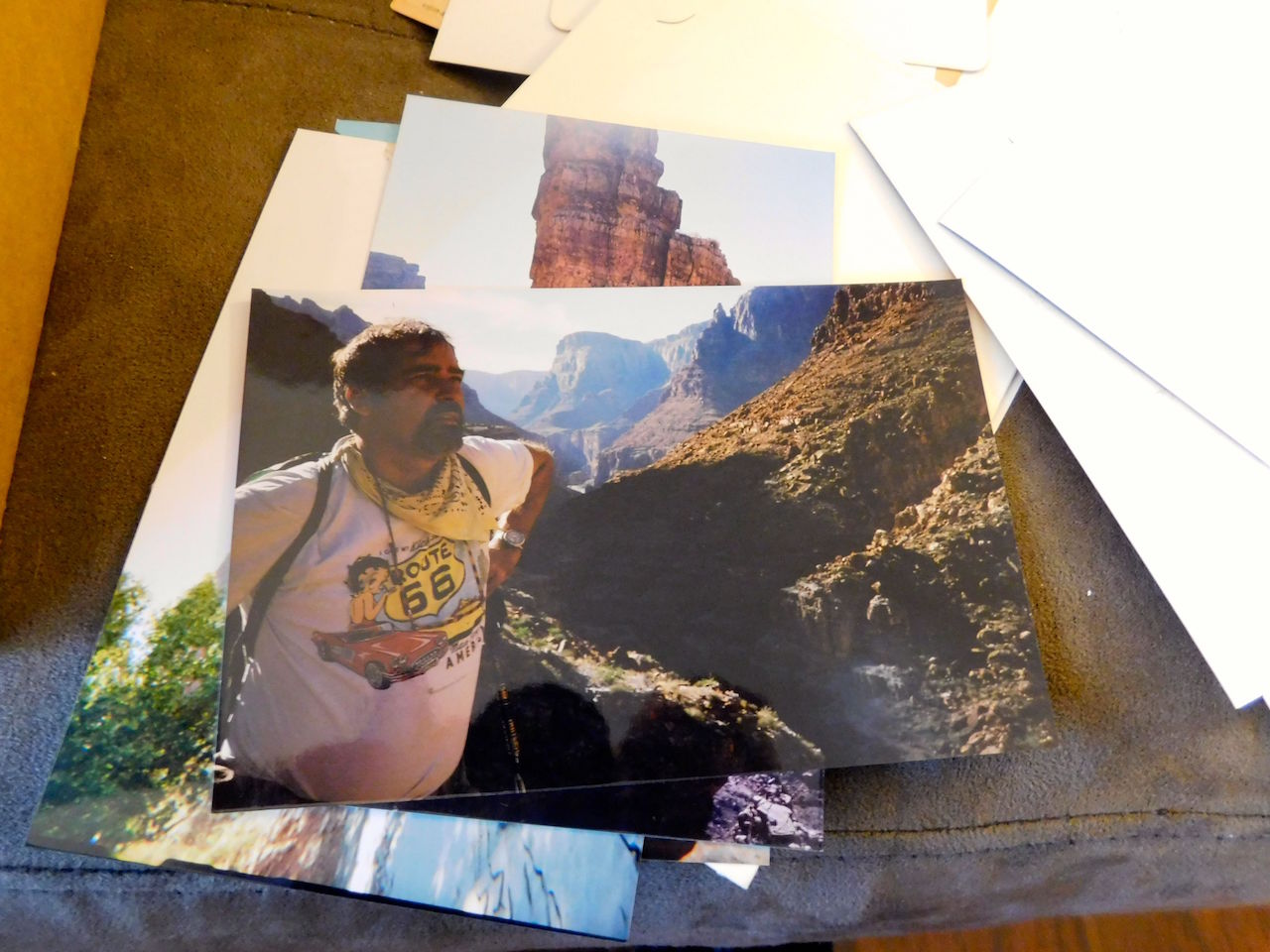

My brother

Tom and I stand on a hill and look down into Salt

Trail Canyon just downstream of Bekihatso Wash and

see as Don Talayesva did almost a century before,

the Little Colorado “shining from the bottom.”

This is an obvious passage to the river because

from the rim you can see far in the distance

below, radiant in the sunshine, the beckoning blue

water and rushing white falls. Getting here has

been something of a business. The route across the

Reservation to the trailhead begins north of the

Tuba City cutoff, already close to the middle of

nowhere, and then travels on dirt roads over

twenty-five miles of red rock and open space.

Again, canyoneer Bill Orman has mailed me a

detailed road log. But it has been a year or so

since he has visited Salt Trail Canyon and he does

not know that a small landmark marking a crucial

turn, a red metal sign with a number, is no longer

there.

On our way here, we have chosen a small side road,

and though it was the wrong one, we eventually

connect to the correct path and picked up Bill’s

other carefully recorded landmarks: three beat up

hogans on the left, a small cluster of whitish

stones, the round rock foundation of an ancient

hogan. Soon we pass a flock of sheep and a pack of

sheep dogs tears across the desert to intercept

us. A wildly woolly black and white, tassel-eared

dog barks angrily at the door. Tom guns the engine

but the fast, protective dogs follow a quarter of

a mile before they are satisfied that the sheep

are safe. I see them in the rearview mirror, no

longer running, but still barking and sneezing and

licking their noses in the cold air.

Now as we look into the canyon, a bright red Chevy

pickup descends a hill and parks beside us. We

chat for a while with the driver, a Navajo hired

to watch the sheep. He knows quite a bit about the

canyon. He tells us that when he was young he once

descended Salt Trail Canyon and trekked all the

way to the confluence and exited out Beamer and

Tanner. He offers few details of the trip except

that he had lost his wallet somewhere in the Gorge

and that it was returned months later by

ichthyologists studying the Little C’s fish.

“It’s very steep in there,” he says, and

points to a small cairn marking a faint trail into

the wash above the drainage. “You start there and

then go down to where it drops in. It’s very

steep.”

“You still go in there sometimes?”

He laughs. “I’m not in condition anymore.”

Talking with him is exceedingly pleasant. Right

away I recognize the type. Typical of Navajos, he

has a soft Indian accent and a modest manner which

might have be mistaken for innocence but which is

really only civility.

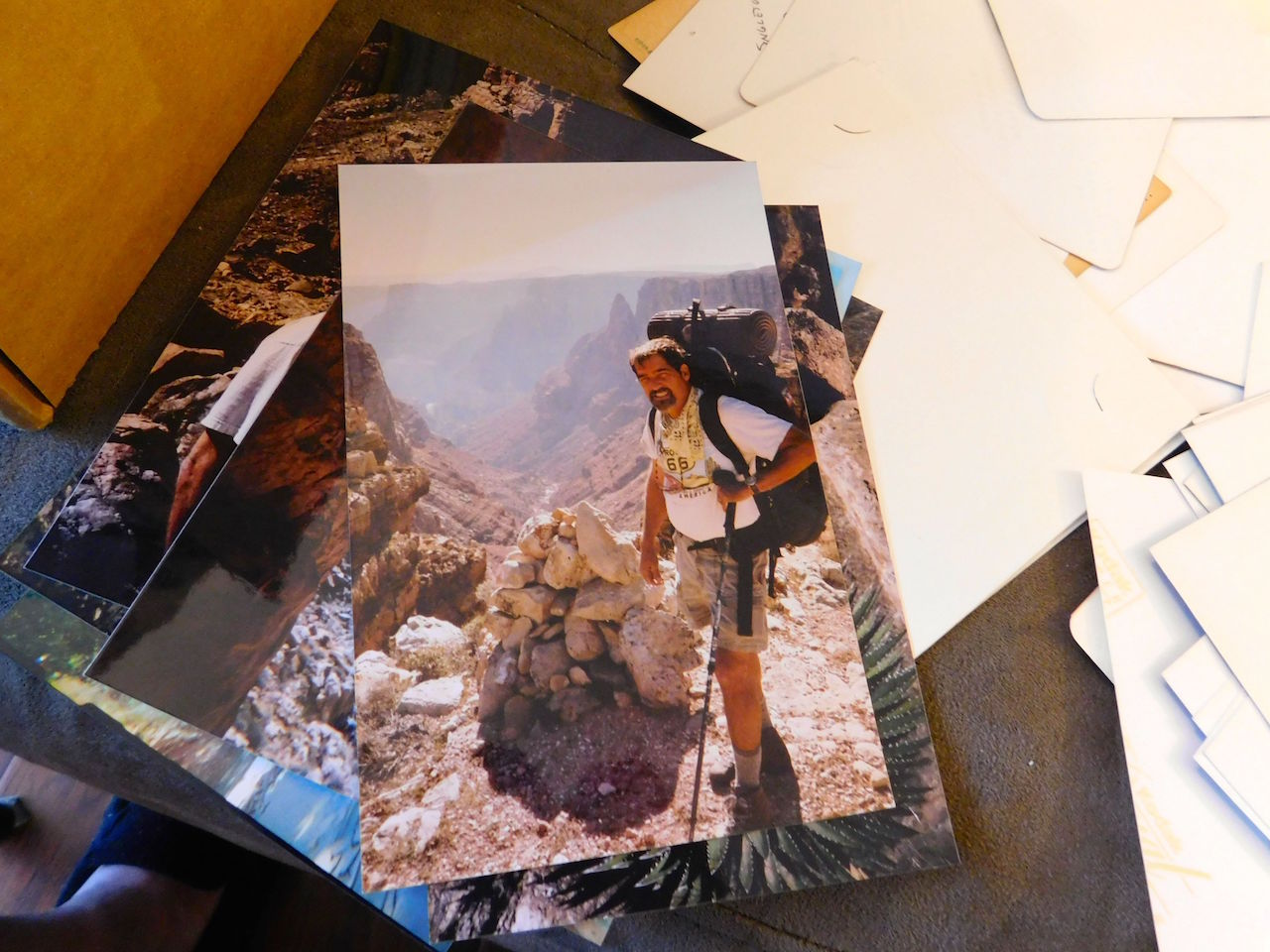

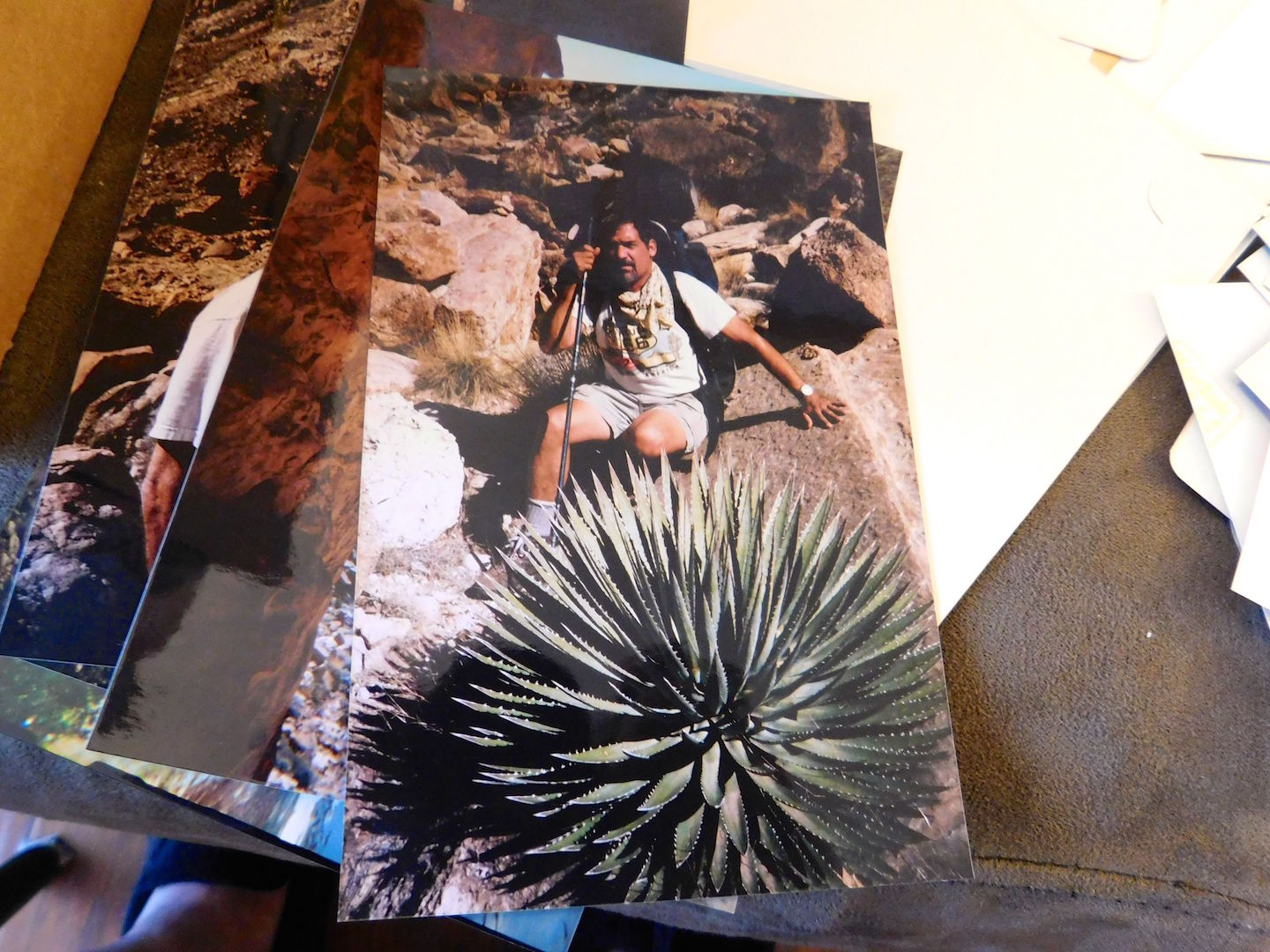

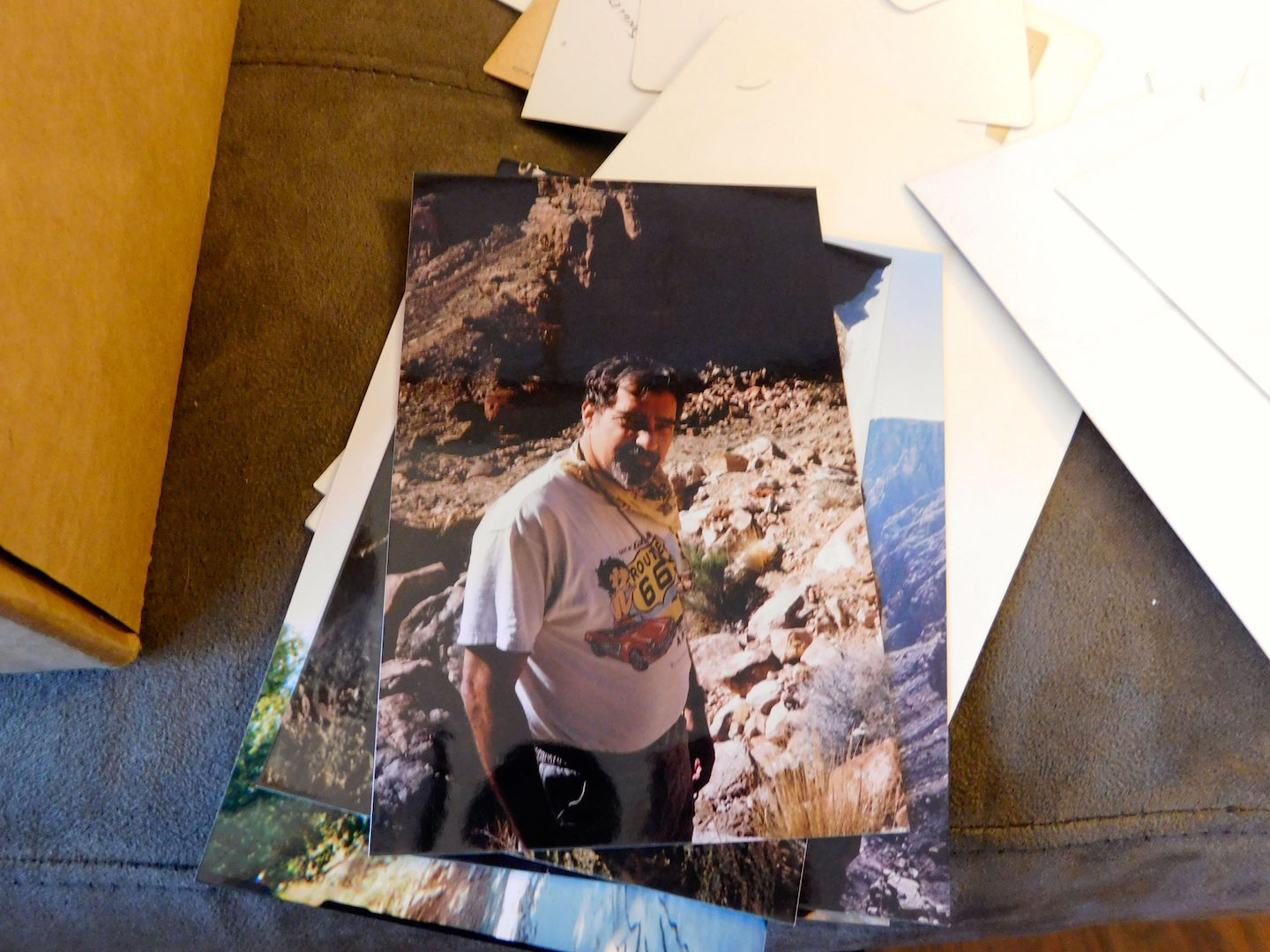

Tom and I drag our packs out of the truck bed.

They are heavy. We are packed for a winter hike.

We’d spent an icy night near Flagstaff where the

temperature had fallen to the low twenties and I

don’t know how much warmer it will be as we

descend into the Canyon. We are loaded with down

coats, gloves, sweaters, wool caps, long fleece

pants and heavy sub zero sleeping bags. Accustomed

as I am to hiking in the heat, it is difficult to

put aside the urge to pack a lot of water. We

carry a gallon each.

The trail leads down between two tall cairns which

stand like sentinels to the Gates of Mordor. From

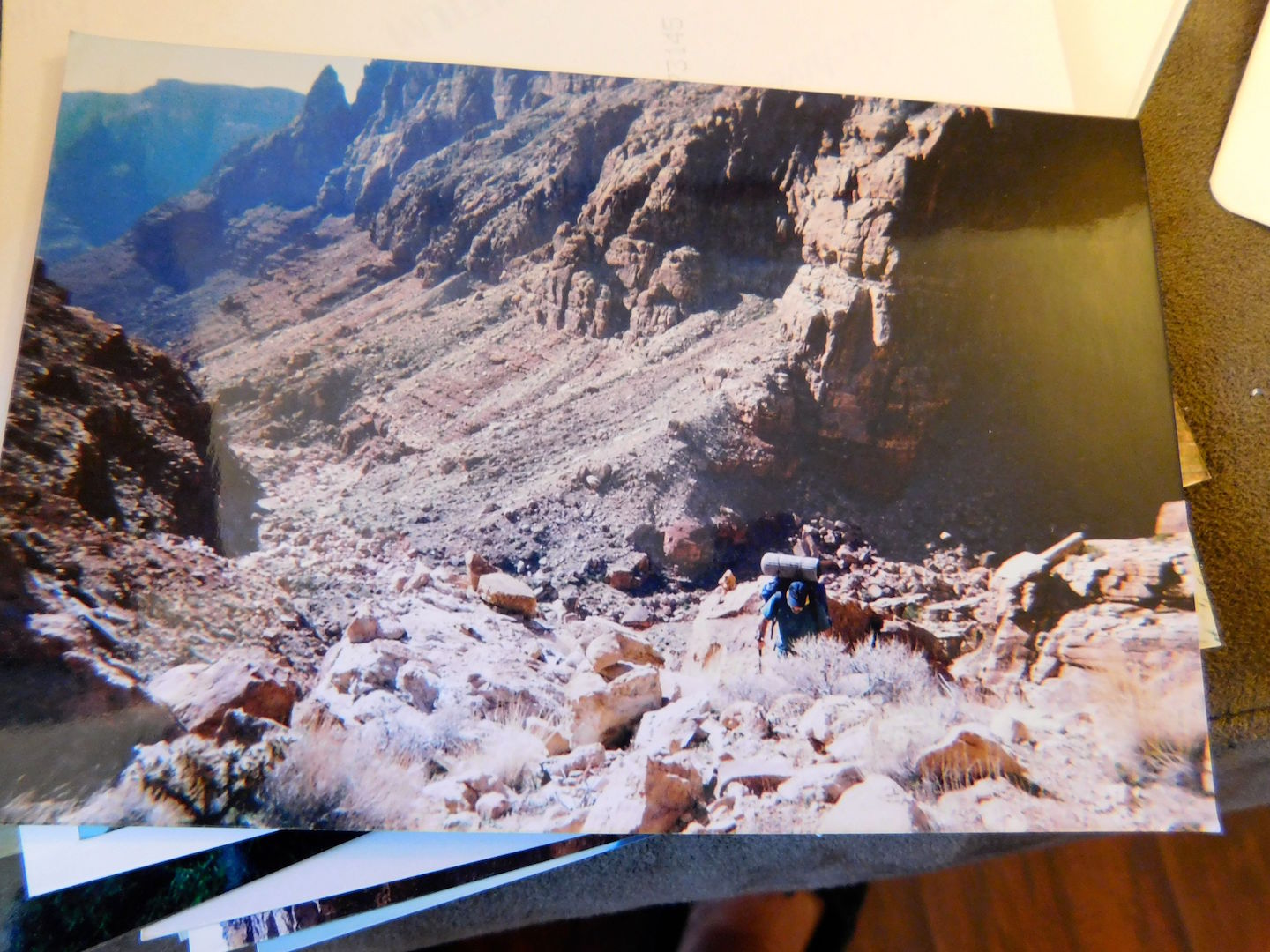

here the route fairly plunges over the edge. While

hiking the Horse Trail with a big pack is

challenging, and Blue the Spring Trail

perilous, The Salt Trail is, well, medium

dangerous, at least for us. There are few places

to make a straight-air fall, but there are plenty

of spots to stumble and break every bone in your

body. For the hardcore canyoneer, the passage may

seem a dreamboat with just enough challenge to

make it interesting. For my brother and me,

however, it’s different. With the heavy packs

balanced on our backs, working down the chute of

jumbled yellow blocks is difficult and scary. Tom,

in particular, is at a disadvantage. Although he’s

a strong hiker, he’s not all that fond of it; he

has only come along because he wanted to look at

birds. Those heavy, three-hundred-dollar Swift

Audubon binoculars swinging from a strap around

his neck aren’t helping much. Despite my warnings

of what the terrain might be like, he had still

imagined walking upright on something resembling a

trail. In addition to this, he has ignored my

advice and stuffed into his pack many glass

bottles of Redhook beer. He has decanted a pint of

another specialty brew into a plastic canteen

stuffed into a side pocket. The cap is loose. A

hoppy aroma follows in his wake. Worst of all, he

is a studied doomsayer. At every precipice he

imagines a fall and supplies with many adjectives

the details of shocking compound fractures. If I

point out an interesting rock, he is apt to make

dark allusions to its precarious position and

comment on the damage such a heavy object would do

if it were to trundle over your skull. In the

distant roaring of jets, he imagines approaching

flash floods and often pauses to evoke appalling

visions. All this crepe hanging fills me with

dread. My mind is laden with morbid thoughts of

tragedy and catastrophe.

Granted, he isn’t enjoying my company much either.

My pedagogical lectures on the use of a walking

stick are wearing him down. I can’t help it. He

considers the stick an inconvenience, just

something else to carry or trip over. When I

express my exasperation at his refusal to be

instructed, he suggests a use for the stick not

mentioned in the REI brochure.

There is also the matter of his shoes. Tom doesn’t

have any heavy- duty boots so I have lent him my

old pair of freshly-resoled Zamberlans. They are

not working out. Behind me I hear a hair-raising

shriek which chills my bones. I turn to see him

doing a sloppy pirouette against the sky. Then he

lunges for the rock and clings for dear life with

both arms to a coffin of sandstone. I’m thinking

that this prophet of doom may be right. “It’s the

shoes,” he says. The new waffle tread, he claims,

sticks to the rock. I don’t know what he’s talking

about. “It’s like walking across glass with

suction cups,” he insists. I think he’s crazy but

we swap shoes. Surprisingly, this seems to help.

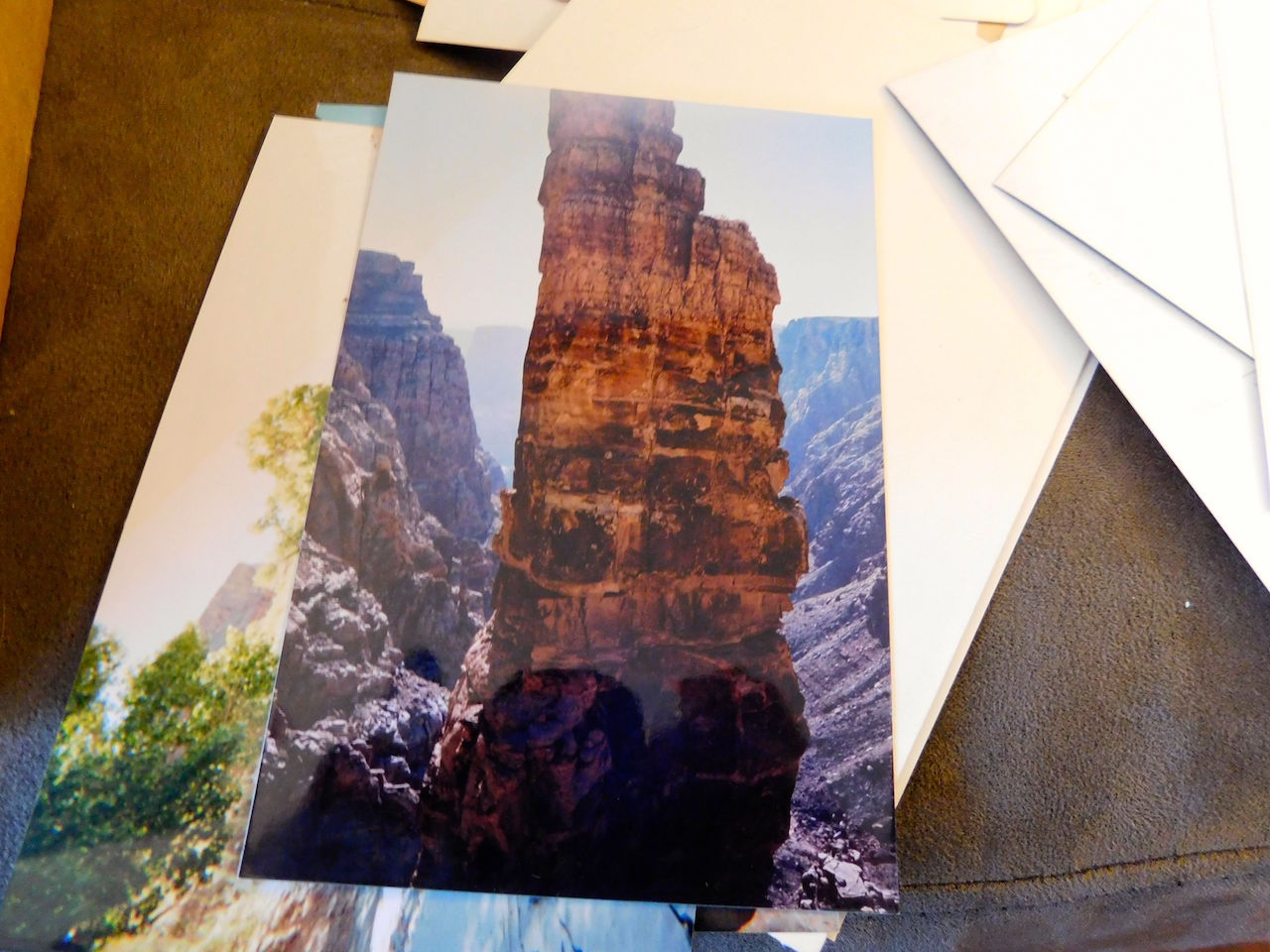

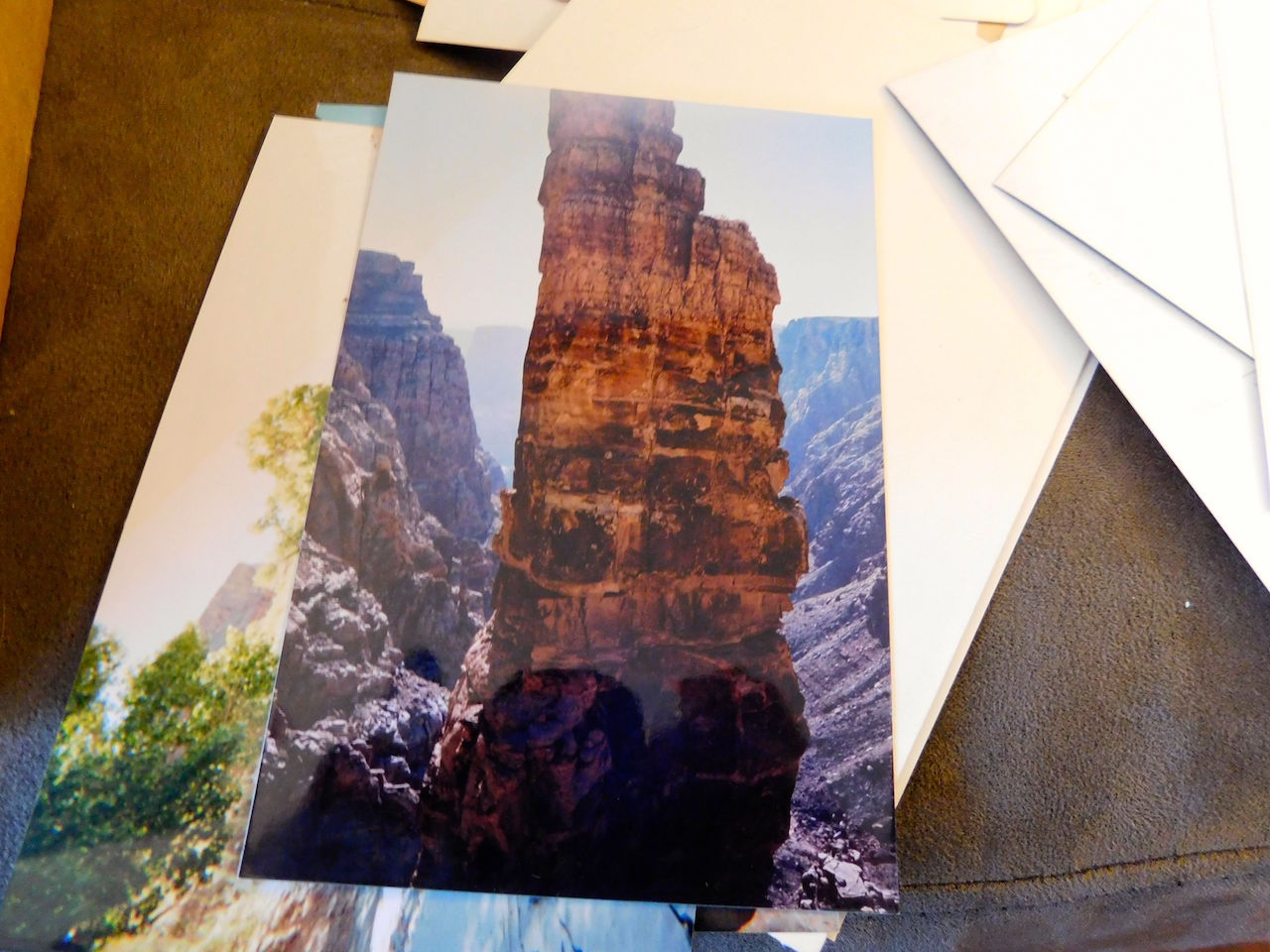

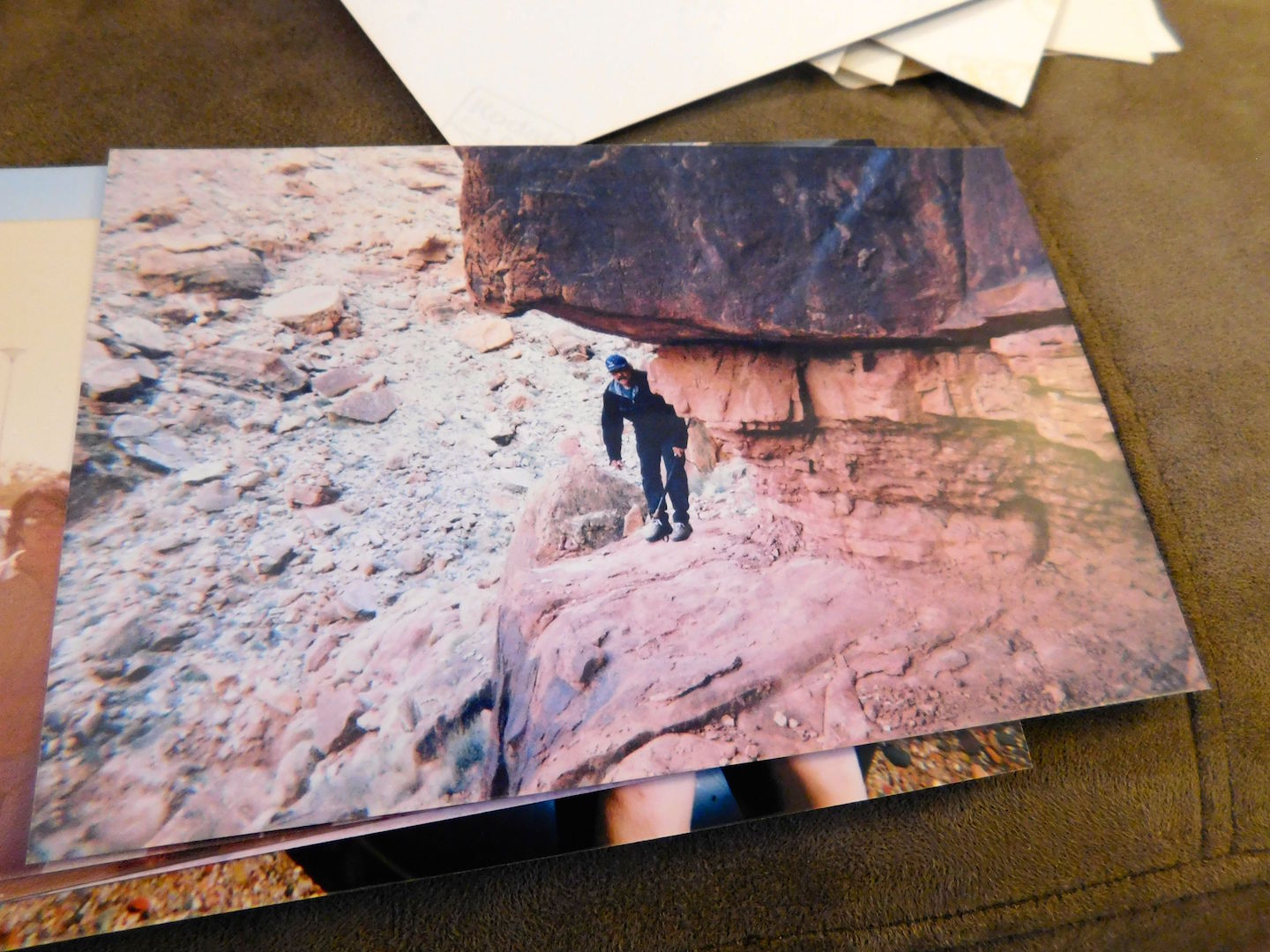

Below the worst of the boulder jam soars a

towering pillar of Moencopi sandstone. Leaning

against the base of this pillar was once a rock

adorned with carvings and paintings of chickens,

the Chicken Shrine. I see no pictures on any of

the stones here now, but when Don Talayesva hiked

the Salt Trail in 1912, he and his companions left

offerings of dough and feathers here and crowed a

little in order to assure success with poultry.

The other places chronicled in Talayesva’s account

are perhaps impossible to recognize because the

descriptions of them are vague. The Chicken

Shrine, however, was undoubtedly at the foot of

this unmistakable spire. Along the way, I have

looked for rock art or pottery, but there is

nothing. Bill Orman has told me that he once

discovered, a little off the route, a large

portion of an Anasazi pot decorated with a jagged

black and white design. He also described to me a

place where straightened sticks, looking a little

like arrow shafts, were concealed in a small cave.

I find the spot and take some pictures. Just what

these sticks mean or how old they are is a

mystery, though they appear as if they are some

kind of an offering. In another small alcove lower

in the formation, I find another dowel-like stick.

Bill Orman has also told me that atop the Redwall

above the river lie two large cairns of jasper. A

Hopi friend told him that these were built by Hopi

pilgrims over the centuries. At the end of a Salt

Expedition each devotee would, it was said, leave

a single stone. If this story is true, it might

well provide a documentary record of the

expeditions from ages hence. An archeologist could

count the stones and arrive at the number of

devotees who had made the journey. It would be

reasonable to assume, of course, that the

tradition of placing a rock did not necessarily

start with the first or even the hundredth

pilgrimage, but it would tell how many had

worshipped at the Salt Mines or the Sipapu since

the tradition started. Another Native American

friend of Bill’s, however, said that these cairns

looked like graves. The story behind these rock

piles may never be known. Looking to Sun Chief

does not help to resolve the question; Don

Talayesva mentions nothing of these cairns in the

record of his Salt Expedition.

Tom and I descend farther into the canyon

following cairns. It’s easy to stay on course and

the canyon relents a little from time to time; we

sometimes find ourselves striding along on an

obvious trail. On the left-hand side of the

canyon, for instance, a long, flat stone “walkway”

traverses an overhang along a wall. Nearby, in a

sandy little basin above a huge, dry plunge-pool,

we drop our packs. Getting dark. We have passed

small tinajas full of water, each of them

reminding me of the weighty load I’m bearing on my

back. I haven’t drunk one drop. We spread out our

flimsy pads and drape our heavy Hollofil bags on

top.

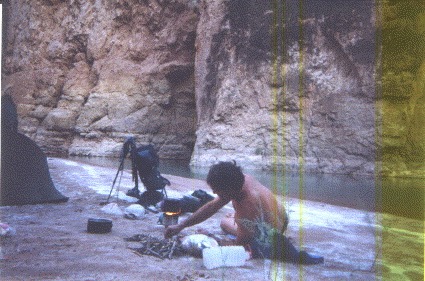

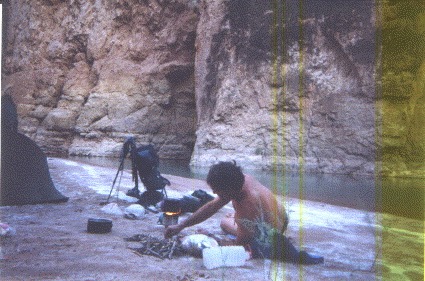

Winter is a quiet time in the canyon. We have seen

no lizards, no squirrels, not even insects, aside

from a few pallid winged grasshoppers. Tom’s total

bird count: one rock wren. We boil water on my

tiny Honeybird gas stove and pour cups of boiling

water into pouches of freeze-dried backpacker

stroganoff and lasagna. I’ve left my wood burning

stove at home. Though it is convenient on a long

trek, on a short one it is not worth the hassle of

keeping the thing stoked and putting up with soot

begrimed pots.

I prepare dinner with such care that I wonder a

little if cooking is not the entire object of the

hike. Into the lasagna I dump the entire contents

of a small container of parmesan cheese which I

stir in with chopsticks. I also add a square of

real longhorn cheddar, a handful of dried

mushrooms and a spoonful of dehydrated onions.

I’ve got something else also. Wonderful Mexican

Cotija cheese, salty and rich. I crumble a chunk

over the top. To make it even better I include a

special ingredient–chile pequin. This is in the

form of an orange powder I have prepared by

pulverizing the small, dried chiles in a coffee

grinder and sifting the result through a wire mesh

so that no remnants of the yellow seeds remain.

Hotter than the hubs of Hell, a small pinch

sprinkled over any dish will add the necessary

fire. Every hiker has his own crazy ingredients;

dreaming up recipes is half the fun. The light

continues fading, and as we finish eating, I feel

a sense of satisfaction that we have timed things

well enough to avoid the misery of cooking in the

dark.

Soon it is night. Satellites fall across the sky

and the long white needles of meteors flare like

sparks struck from flint. We watch Orion, the

seven sisters, and just under the canopy of stars,

the silent lights of passing planes which I

imagine are glittering indecipherable codes, each

spelling a single word over and over. We lean back

against a stone drinking cold, bottled beer. Tom

says he sees ghost lights twinkling like fireflies

against the black shadow of a cliff and I’ll be

damned if I don’t see them too. After a while the

rising moon turns the sky into a mistiness full of

light and depth, the cliffs emerge from the

shadows, and the mysterious lights disappear.

You don’t see such shows of light either real or

imagined with a roof over your head. My friends

who don’t hike often seem appalled when they learn

that I rarely pack a tent. They shudder to imagine

a night uninsulated by at least a protective film

of nylon. But having walked away from the

machinery of civilization, I am completely at

ease. The closest automobile is the one we left at

the rim miles away. But aren’t there mountain

lions, they ask. Not many, and what good would a

tent do? The claws of a lion bent on my demise

would slash like straight razors through any

fabric. But snakes, they insist. Aren’t you afraid

of snakes? Not really. Rattlers are uncommon here

and I would count seeing one as a benefit. I have

yet to see a pink Grand Canyon rattlesnake.

Admittedly, a snake bite here would be nothing but

trouble. Tom’s doomsaying makes me dwell on this a

little. What exactly are the chances of a

rattlesnake bite? Aside from their scarcity, the

fact that rattlesnakes are not particularly

aggressive makes them unlikely assailants. I have

read that the profile for a rattlesnake bite

victim generally involves the following scenario:

male in his twenties, drunk, holding snake. Most

other bites occur when the dumbbell is trying to

harass or kill the rattler. Stumbling upon a

rattlesnake or sharing a sleeping bag with one are

not common ways of getting bitten.

I recall a snake story which occurred near the

ultimate terminus of this very drainage. In his

classic account of his 1907 expedition to Sonora’s

Pinacate mountains, Camp-Fires on Desert and Lava,

William Hornaday recounts an anecdote which

suggests that even a snake in the hand may not at

times be any more dangerous than one in the bush.

The story regarded his geographer, Godfrey Sykes,

who wished to set his aneroid for a more accurate

measurement of the Pinacates’ elevation. The only

sure way to do this was to walk to sea level, to

the sandy shores of the Sea of Cortez, a couple

dozen miles to the south. There he could set the

pressure-altitude indicator of the device to zero.

Aside from being a good geographer and as

respected a writer as Hornaday, Sykes was also one

hell of a hiker. One morning, without telling the

others, he set out for the sea. Having made the

difficult crossing of the sand hills, he found

walking across the flats easy. At the gulf, he

adjusted the scale of his instrument and after

gathering a few shell specimens for Hornaday, he

started back. The full moon illuminated the way

and he arrived at camp at half past one that

morning. His pedometer measured 43 miles. There

was, however, an incident on the way back. I best

let Mr. Sykes tell the rest of it himself:

“The net zoological result of my pasear was a few

little birds of unknown species, a jackrabbit or

two, a coyote and a little coiled up rattlesnake

evidently suffering from the chilly night air. I

put my hand on the snake, thinking it was a shell,

and never discovered what kind of snake it was

until, as he slid through my fingers, I felt his

rattles! At that I bid him a hurried adieu and

left him to find warmer quarters.”

I know only one person who has suffered a

rattlesnake bite. My friend of many years ago, Joe

Kraig, was once bitten by a sidewinder. He was

trying to force feed a pet rattler by stuffing a

mouse down its throat. In the process he

inadvertently inserted his thumb into the snake’s

mouth. Both fangs got him. In this case the bite

should not have been a dangerous one because, as a

precaution, Joe had milked the sidewinder just

before attempting to feed it. Joe squeezed his

thumb and two pure red droplets appeared. No venom

seemed to have been injected. Thinking he was in

the clear, he put the snake back into its cage and

went about his business.

A half hour later he noticed a dark red line of

discoloration moving slowly up his arm following

the course of the radial artery. His wife called

the hospital and soon he was greeted by the

excited staff of doctors, nurses, candy stripers

and janitors who were waiting eagerly at the

emergency room door. By now Joe’s face was

swelling up. I don’t remember whether he was given

antivenin or not, but the snake nearly killed him.

Joe was always careless with snakes. He was

intrigued by them and collected all kinds. One day

on the Reservation along I-40 near Sanders, Joe

stopped to pick up a hitchhiker, a guy he knew,

Emerson Roanhorse, who was hitchhiking along the

frontage road. “Ya’ ‘at eeh, Emerson. Where you

headed?” Emerson pointed ahead Navajo-style with a

pursing of the lips and an upward nod of the head.

“Goin’ to my Aunt’s, Joe. Right up here by Houck.”

“How’s your sister doing, Emerson?”

“She’s okay. Working at Whiting Brothers.”

At this point, Joe braked for a stop sign and a

burlap bag slid out from under the front seat. A

rattler slithered out. As a general thing,

Navajo men are not much shaken by rattlesnakes,

but the unexpected appearance of one inside a car

is enough to test anyone’s resolve. Joe’s

passenger must have weighed two hundred pounds,

but he went through the window like a jackrabbit.

The window was rolled half way up and how he got

through without breaking the glass is hard to say.

Joe was immediately contrite. “Damn, I’m sorry,

Emerson. I didn’t know that would happen. Hang on.

I’ll resack him.

“Ah, Ch’iidii! You dumb bastard. Why don’t

you tell me you got a snake in there. Are you

crazy?”

“Sorry. Sorry.”

Emerson cooled down.

“Just put him back in the bag. Hurry up. I’m

already missing dinner.”

Another time, on holiday, Joe was tubing

down the Salt River near Phoenix when he came upon

a fine black and yellow king snake in the brush

along the shore. Enthusiastically, he grabbed it

and wrapped it around his neck and began paddling

to meet his party of friends at an island in the

middle of the stream. Now the king snake has a

reputation for being an amiable creature, a fair

pet as far as snakes go, but this one opened its

mouth and grabbed the soft flesh of Joe’s throat

like the clamp on a jumper cable. At the island

Joe paced up and down the shore cradling the

snake, followed by his sympathetic companions.

Meanwhile, floating clusters of tubers, many beery

and unsteady on their feet, arrived at the island

full of pitying interest. A crowd began to gather.

Joe and his snake had become a riparian

attraction. “Over here!” someone would yell across

the water. “A guy’s got a snake on him. Hangin’ on

his throat!”

“No shit?” Then, “Damn! I’m stuck in an eddy.

Don’t let him get away. I’ll be right there.” (The

sound of furious paddling)

Joe was thinking that he could do without a

portion of this attention. His main concern was

how to dislodge the snake without injuring it.

Every one of the hundred and ten spectators,

though, had the same idea. “Burn him off!” they

cried. “Here!” and they each thrust a flaming Bic

lighter in Joe’s face.

Even with the snake hanging painfully from his

neck, Joe couldn’t help but marvel at the

excitability of these wet, slightly-toasted

individuals. Almost all of them had lighters which

they adjusted so that a foot of orange flame

gushed out. Inspired by many twelve packs, they

were fired with an earnest desire to serve him, a

boozy sympathy, a philanthropic zeal almost. But

at this point all Joe wanted was for them to go

away. “Jump in the water,” one suggested.

“Drown the sonofabitch off.”

That seemed like a fair idea. Joe jumped in.

In the annals of human arrogance there is scarcely

an example which equals Joe Kraig’s attempt to

hold his breath longer than a king snake. In

short, he couldn’t do it, and these two marvels of

nature remained connected until the reptile tired

of the game and dropped off of its own accord.

In the morning Tom and I leave our packs at our

camp in the wash and trek down to a deep fissure

with huge impassable pour-offs. The route crosses

the wash above and ascends in the form of a faint

trail to the top of the Redwall where it continues

a long pace before dropping down to the river. We

trudge up the steep slope. Below we see the

shining water. The bluest river in the world? I

have no doubt, though as I have mentioned, it has

another face when it runs a walnut brown and at

the confluence it mixes with the green water of

the Big Colorado the way cream swirls into coffee.

We’ve been here long enough. I’ve promised

my young son that I’ll stay closer to home. He

worries that I’ll never come back. He shouldn’t.

The eight days I spent in the Gorge with my

brother Jeff were the longest time I’d ever spent

away from him, and I wonder a little that it has

already been two years since Jeff and I walked

along the sands of the turquoise waters below Salt

Trail Canyon. Just what dreams compelled us to

hike the Gorge are already fading into memory.

Many wilderness travelers express their desire to

find a spiritual enlightenment in nature, an

answer to the mystery of their lives. I am all for

this, but personally have long since given up such

seeking, for to me the answers seem only to appear

in the form of the most arcane metaphors, at best

disquieting and always indecipherable. I count

myself then, superfluous? fortunate to have

been so untroubled by spiritual longing for I

suspect that this is because I have found enough

to satisfy me. An experience itself unencumbered

by a recondite quest is more than sufficient.

I remember a Navajo woman I once bought jewelry

from asking, “Why do you do that? Why do you go

down in there?”

“For fun,” I told her, and it was a true answer.

The river is just as I have remembered it, a milky

blue. We have no time to linger here. We have jobs

and obligations. Against my inclinations, I try to

sense something of myself in the huge and timeless

canyon and find nothing. Time flies more quickly

for a man than it does for a canyon and a canyon

has no promises to keep. We ascend to a high place

overlooking the shining blue river and listen to

the white sound of rushing water.

|

<video controls="controls"

src="Salt%20Trail%20November%202002%2018.mov"

width="420"

height="345"> Your browser does not support

the HTML5 Video element. </video><br>

salt%20trail.mov

|

Steve Salt Trail 2002 d.jpg

Steve Salt Trail 2002.jpg

Tom on the Salt Trail 2002.jpg

tom Salt Trail 2002.jpg

|