AUGUST 7, 2008

GO TO SIMILAR PAGE WITH PICTURES OF THE SAME TRIP:

FORT BRAGG

Turkeys Page

BIRD LINKS

Essays

Animals

Places

Go back to Memoirs and Essays Page

Go back to Tom's Home Page

|

Auk—Pelagic

Trip—Debi Shearwater—Arthur Singer—The

Short-tailed Shearwater—"Mutton Birds"—$185

for a Day-Long Sea Jaunt—"A Crappy Hotel in

a Bad Neighborhood”—The Glass Beach—Patches

of Blackberries—Crumbling Cliffs—A Familiar

Brewery—Blue Herrings—Lighthouse—A

Graveyard—A Bum Having Fun with a Bottle and

a Gun—Uncle Donny Pops—Blue Whale—Chumming

with Pop Corn—Auklets, Jaegers, Shearwaters

and Albatrosses—A Baby Cowbird Bites

Me!—Follow That Bird!—A Salmon Shark—The

Cowbird Heads for Home

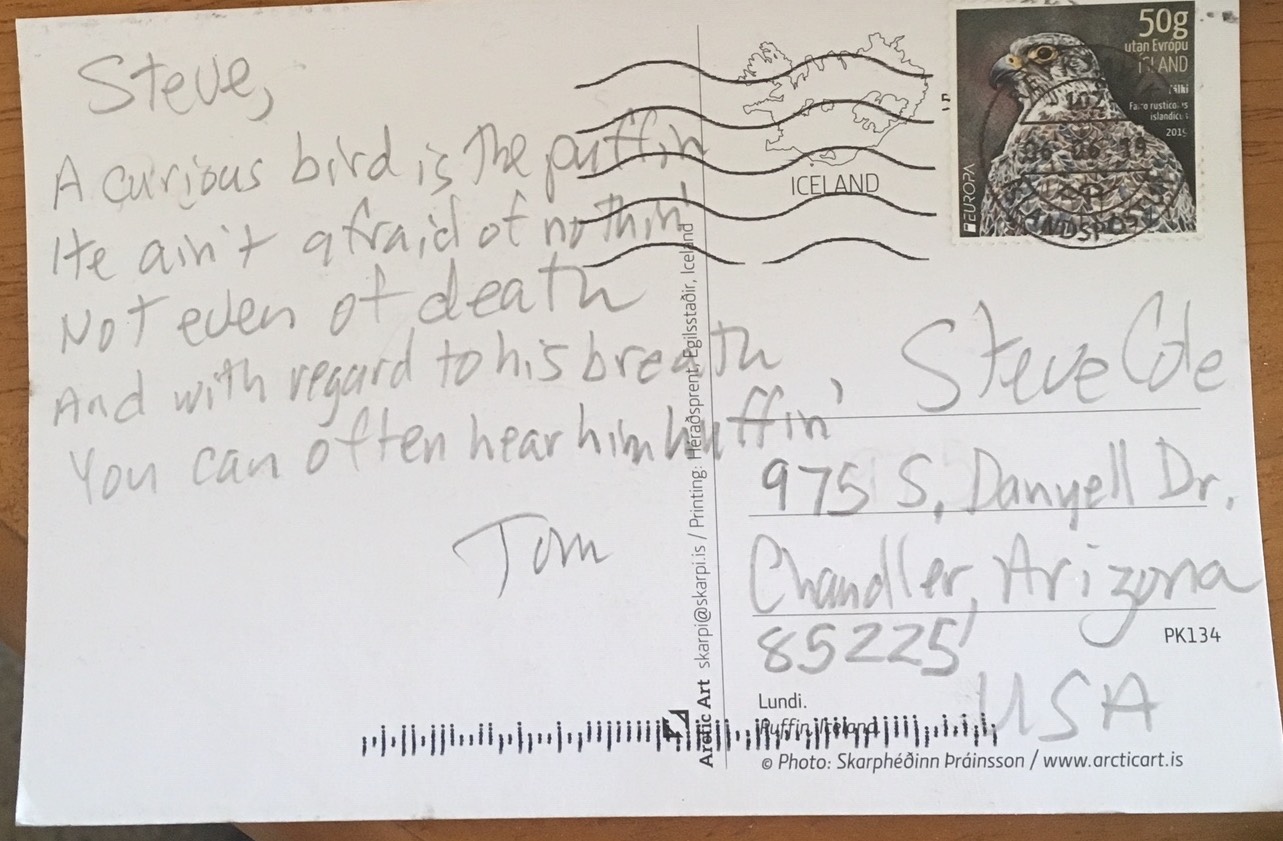

The Trek II My photo: Short-tailed Shearwater Sooty Shearwater Migration    Long-tailed Jaeger.png Debra Shearwater.jpg In The Big Year, with Steve Martin, Anjelica Huston’s character, Annie Auklet, is modeled on veteran pelagic-trip leader Debi Shearwater. If you're a crossword puzzler, you know that the cue "seabird" calls for the word, "auk" and the auks and their allies—murres, puffins, auklets, murrelets, guillemots, and dovekies—are one major group you are looking for if you go on a pelagic trip. I had never seen a single one of these birds, nor had I ever seen any of the tubenoses: shearwaters, fulmars, albatrosses, storm petrels, etc., so years ago, I asked a friend how one went about seeing any of these pelagics. He told me to call up Debi Shearwater. "Who?" I asked.    whiskered auklet.jpg crested auklets pigeon guillemot.jpg "Debi Shearwater," he answered. "She organizes pelagic bird watching trips off the coast of Monterey." "Shearwater?" "Well, obviously she wasn't born with that name; she changed it." I called up Debi and none of her trips fit my schedule. Well, way led onto way, and I didn't get around to calling her back for several years. A coworker last year set me back on track when she gave me a book called Water and Marsh Birds of the World. It was illustrated by the great Arthur Singer, and I started to read it. The short-tailed shearwater caught my imagination as I read. The short-tailed is a pelagic species that, true to the name, visits terra firma only to breed. Like the other pelagics, the bird spends its life flying across the vast, open ocean far from the sight of land. The short-tailed shearwater builds a deep burrow to lay its eggs on the islands between Australia proper and Tasmania, and when it has finished its reproductive duty, it takes once more to sea, flying up to New Zealand and then clockwise all the way along the thousands of miles of western Pacific, past Korea and Japan, over the Bering Straits, and down the coast of California. Then, somewhere well off of the coast of southern Baja, its path leads it outward, over thousands of miles of open sea—half a world of water towards home. The mature shearwaters may find their efforts to breed on the islands somewhat disappointing; the Australians harvest the young shearwaters from their burrows and sell them canned as "Tasmania Squab" or "Mutton Birds." They are considered a delicacy. This at first would seem to present some concerns. There are, after all, too many endangered birds already, and some like the long-billed dowitcher are only with us now because market gunning has been outlawed by governments. Happily, Australia regulates the shearwater harvest now, and though hundreds of thousands of "squabs" are wrested from their burrows and butchered, the species still flies in enormous numbers over the Pacific. The fascinating facts about the short-billed shearwater got me thinking about Debi Shearwater and her sea birding trips, and I booked a $185 day-long jaunt on a ship in Fort Bragg, California. I travelocitied everything, but I made one mistake when I booked a room in the Fort Bragg Travelodge; I checked its user reviews too late. One read, "A crappy hotel in a bad neighborhood." Another, "Don't stay here unless you're a real budget traveler! I was seriously scared in my room." Still another, "Not clean, not safe, actually scary." "Gosh," I thought. "Two of them mentioned safety, and one talked of meth addicts hanging around. This lodge is not for me." I'm the kind of guy that meth addicts bother. Junkies too. For some reason, they see me as an easy mark. I rebooked, talking the nice Asian Indian telephone staffers at travelocity into waiving the $25 cancellation penalty. It was, after all, a matter of life and death. My new lodgings were at the Glass Beach Bed and Breakfast at a good savings. I telephoned and told them about my Travelodge fears, and they in turn sympathized but neglected to tell me that they were exactly—I mean directly—across the street from the lodge and that the deadbolt lock on my cottage was broken. But I didn't mind because it was such a nice place, and I got free breakfast.  Glass Beach Bed and Breakfast The Glass Beach itself was only five minutes from the B&B, and I walked there, getting a good look at the Travelodge. It didn't seem so bad. I went past a lumberyard and found a dusty path between giant patches of blackberries. Many of the berries were ripe. Along the path were also ice plants—those big stalked kind with the blades looking like dill pickle spears. A few families with kids were on the path and down on the edge of the ocean. The beach was surrounded by crumbling bluffs and rocky cliffs. The water was filled with floating seaweed, long yellow-brown tubes as big around as your arm with bulbous, frilled ends. The air had a disagreeable smell. Some blackbirds were flying in and out of some brush offshore, and I hurried over in the hopes that they might be tri-colored blackbirds, but no luck; they were the garden variety red-winged kind. Back near the shore, I raised my binoculars and saw a fairly large bird with white wing patches. It seemed a weak flyer as it struggled to get over the water to the cliffs. Its feet were bright red. "That's a pigeon guillemot!" I said to myself in surprise. I was pleased at first because I had always wanted to see one. I was also a little disappointed. The pictures in my field guides led me to believe that this was a true pelagic, never near shore. A lot of the romance I'd built up surrounding this species faded when I saw it puddling around in the water like a common mud hen. But it was still a great bird to get on my list. On the rocks nearby was a group of black turnstones. Funny; they were far and away more pigeon-like than the guillemot, as is the ruddy turnstone, which I see at the family beach house on the Sea of Cortez. The black turnstone is also present there. The black oyster catcher, which I would see flying by in the distance a little while later doesn't seem to be on the east side of Baja. A giant western gull was flying towards shore with a long ribbon of seaweed in its bill. Was it just showing off? No, it landed on a rock, and I could see that there was a crab tangled up in the seaweed. The gull started tearing off the crab's legs and flinging them down its throat whole. A black turnstone waddled up to see if there might be anything left for him. I was happy to get two more life listers at the beach, Brandt's cormorant and the pelagic cormorant, and then I was ready to go back to my room. It had already been a long day. I'd taken a jet from Phoenix to Sacramento and driven for hours on the long, twisting two-lane roads to Fort Bragg. I had the whole next day free, so I would have plenty of time to explore the beach some more later. I remembered that when I drove into town, I saw a brewery, and it was just three blocks from the Glass Beach Bed and Breakfast. My inner compass unerringly led me there. To my surprise, I had heard of the place. It was the North Coast Brewing Company. They make Seal Ale, which is for sale in my local Sunflower Market. I took my place at the bar. Through the window across the street, I could see the actual brewery, a separate building. The bar sold nothing but their homemade stuff. No Miller Lite® or anything else like it. Good for them, I thought. I got an India Pale Ale and chatted with some tourists who were drinking Old Rasputin, a Russian imperial stout. One of the guys had lived in Phoenix as a child. The barmaid was a native of Fort Bragg. Born there. An American guy and his German girlfriend wanted to talk about birds after they saw my bird book. They had many misconceptions. You know the kind: that birds are ubiquitous except for maybe the ostrich, that they migrate by flying at 40,000 feet and riding the jet stream, and so on. I always try to straighten people out on the basics. "No, no," I said. "You probably didn't see a crane. We've only got two, the whooping crane and the sandhill crane, and neither was a likely sighting for you. You probably saw a heron, a great blue heron." I had a feeling of satisfaction because later, I knew, they would be passing on this new knowledge and would say to a friend, "No, no! That isn't a crane. It's a blue herring!" The brewery served pricy food on white tablecloths, so I went and ate at a Mexican restaurant. The next morning, I drove around the area. There was a nature walk down to a working lighthouse near the town of Casper, and I took it. Along the trail, I found a noisy little flock of bushtits and a few chestnut-backed chickadees. I'd seen the bushtit five times before but the chickadee only once, in Vancouver. Down towards the lighthouse, you could look at the sea over crumbling cliffs. A sign read: "DO NOT APPROACH THE CLIFF," and it had a drawing of a child in shorts who had stepped too close and had caused the rocky edge to break away and fall, taking him with it. A little later, I pulled my rental car off the side of a road and walked up a path up to a graveyard. All along the trail in the redwood branches, chestnut-backed chickadees hopped and snicked, and I quickly grew tired of them. An Epidonax flycatcher hopped down to the ground and then flew back up into a redwood tree. The graveyard had a sign asking people to be respectful and not to desecrate the graves. Fair enough. I walked through the graveyard and looked at who died and how long they lived and whom they were buried with. One grave marker was made of welded steel in the form of an anchor. It was spray painted green. Obviously, the person buried there had made his living on the sea. He was born in 1941 and died in 2002. Sixty-one years old. I did not desecrate any of the graves.  Graveyard with Anchor Grave Marker I'd eaten up the day driving around. I had seen few birds, but the real idea of this free day was to make sure I wasn't rushed and could ease into the boat trip the following morning. I judged after a time that another visit to the brew house was due, and I walked back to my room. On the way, I ran into a drunken street person. He said, "How's it going bro?" "Great!" I told him. He was drinking beer out of a quart bottle. On his hip was a long barreled pistol in a red leather holster. He seemed to be trying to hide the gun under his untucked shirt. I was glad he hadn't asked for money because I don't like to disappoint gun-toting rum-dumbs. I thought of asking him if he was staying at the Travelodge but thought better of it. About forty-five minutes later, I started off from my room on the way to the brewery. Then I stopped. There was the drunk not a block away sitting on the side of the road. A young guy walked by and the drunk got up and shook his hand. "Damn," I thought. "He sure hasn't gone far." I walked across the street to avoid him, went the three blocks, and then crossed the street again to the brewery. I drank two India Pale Ales. I decided to walk around a bit and find a cheaper place to eat. I ran into the drunk again. Over by the Welcome Inn, he had the holster off his belt and was doing something or other to it. I said to myself, "Are there, like, police in this burg?" Not all of the people were bums. The town folk were everywhere walking. There were some young people, but most of the folks out and about seemed at least fifty, beards and pony tails on many of the men. Everyone looked a little wind blown. One family walked by, and a woman said, "Thank you so much, Uncle Donny! We'll get it next time." Uncle Donny must have popped. Fort Bragg isn't a bad place. A little run down, but not bad. I ate at the Mexican restaurant again. I arrived at the wharf an hour early the next morning. I didn't want to miss the boat by finding out too late that California had a different time zone or something. I knew darned well what time it was, but my compulsive nature would not allow me to tempt fate by arriving on time instead of way early. In a while, Debi Shearwater showed up and asked for ten bucks extra for some fuel tax. Twenty-five others arrived a little later, and after a ten-minute talk on boat etiquette, safety, seasickness pills, and birds, we disembarked. Five of the people aboard were leaders and experts at identifying seabirds and other sea creatures. We hadn't even got beyond the sight of land when one of them started screaming. "Blue whale!" he shouted. He neglected to say, "Off the stern!" or "At six o'clock!" as we were all told to do. Seeing a blue whale, the largest animal that ever lived, was quite a big deal to everyone. We chased it with the boat. We'd stop and wait to hear the animal breathe. It was a huge sound, and you could see the column of spray out of its blow hole. The hump that I saw did, indeed, look blue. The whale would disappear, and then we'd see it rather far away. This made us think that we may have been looking at two of them. After a while, we stopped chasing the whale as it was going in the wrong direction. The boat headed out to sea and we soon lost sight of land. Debi Shearwater had brought a huge bag of popcorn which she explained would be used as chum. I wondered how long it would last, but I needn't have worried. One of the leaders would stand at the stern and every few seconds drop a single kernel into the boiling blue wake. Western gulls appeared, followed the boat, and dove to pick up each piece of popcorn. In no time, there were also Heerman's gulls and California gulls following us for the corn. They would attract other birds we were told. Soon I heard the shout, "Common murre!" and looked to see a black and white bird flying over the surface of the ocean. "Did you get him?" someone asked. "Yes," I replied. "A fine old saddle shoe." I'd been waiting to say that. Murres are in the auk family, also referred to as the alcids. They are very penguin-like, though not related. Like penguins, they are black and white, and they cannot walk well as their hind feet are positioned too far to the rear, but they can fly underwater using their wings. The common murre males were often seen with a chick next to them floating on the water. The next cry was "Sooty Shearwater!" It was a dark bird flying at great speed just inches over the surface of the rolling sea. This was as close as I would get to seeing the short-billed shearwater. The two birds are very much alike and difficult to tell apart, and the sooty is also canned and sold as a delicacy. Unfortunately, the leaders told me that the short-billed didn't generally appear off of these waters until the winter, so I would have to be content with the sooty. The rhinoceros auklet was next. It was resting on the surface. It was a bird I had always wanted to see because of its pairs of unusual white facial plumes and the vertical spike on its bill. I could see neither because of the distance or perhaps because the bird may not have been in breeding plumage when those features are present. When the first black-footed albatross showed up, I started muttering lines from Coleridge's Ancient Mariner. Yes, I knew it was an obvious cliché to do that and really somewhat obnoxious, but I could not help myself, and the other birders, one of whom was on his 65th trip out, seemed to expect it and happily quoted along with me. The albatross stayed with us for food or play the whole trip, and six or eight others came by and stayed too. Black-footed

Albatross.jpg

Black-footed Albatross2.jpg

The black-footed albatross is kind of a goofy looking bird. When it was arching over the water with its long narrow wings, it was a marvel. When it sat on the water, however, it seemed more suitable to the barnyard. With its bulbous bill, it had a familiar look somehow—like a brown hound dog sitting contented in the living room, happy to be at home. Seeing the albatross at rest on the water gave me a clearer picture of what being a pelagic bird means. When you think of pelagic birds, you tend to assume they must either fly or drown, but the ocean is a great habitat not unlike the land to them. If the birds wish to rest, they simply sit on the water. All of them seemed to do this. The western gull, when it wasn't flying above our wake, would float on the surface. So did the little Cassin's auklet. In fact, I don't remember seeing one on the wing. Red necked phalaropes, small pelagic sandpipers, would stream by in stringy flocks, and three species of jaegers showed up along with another shearwater, the yellow-footed. Far offshore, we would occasionally see buoys floating in the water. They were sturdy metal contraptions each with a bell on it so that seafarers could hear them on a foggy night and not run into them. As we passed one such buoy, I looked up to see a fluttering little bird fighting against the wind. "What was this little pelagic?" I wondered. "Was it a storm-petrel?" I heard one of the leaders behind me say, "Well, for goodness' sake!" The little bird fought its way around the boat and finally alighted on the cabin roof. It was an immature brown-headed cowbird lost at sea miles from shore. It had been sitting on the buoy and left it for a free ride with us. I'd never seen a baby. Its breast was heavily streaked with brown. It made its way to the walkway on the side of the boat where we threw it bits of cracker. It hopped over and ate them. The cowbird would occasionally abandon ship and find itself battling the wind to catch up with us before it alighted again. Some of the birders grumbled about it. The cowbird is a pest that lays its eggs in the nests of favorite songbirds such as the warblers. They don't make their own nests. The baby cowbird that hatches is bigger and stronger than the other nestlings, and it grabs up all the food that the parents bring to the nest and in the end tips the other baby birds out. We had one of these villains in our midst, but I am particularly fond of the blackbirds and cowbirds, so I was happy to have him aboard. One of the guys mentioned that he had never seen a bronzed cowbird, and I was able to tell him about the times I had seen it.  Cowbird On Board Everyone ran forward and Debi continued shouting to the skipper, "Don't stop the boat. FOLLOW THAT BIRD!" The skipper gunned the engine, and we went after the petrel. I could see it ahead winging over the waves. We kept up with it for quite awhile. In the meantime, Debi Shearwater was yelling, "Pictures! Take pictures!" She wanted to prove that she had got the bird. There were two guys with those cameras with long lenses attached—more like telescopes. The guys were snapping photos. "This is why we fucking came!" Shearwater shouted. When the bird had outdistanced us, one of the guys showed one of the pictures he had taken. I was amazed. It was a perfectly clear shot of the black and white petrel angling over the sea with its pointed wings tilted in the camera screen. The bird was an Hawaiian petrel and was one of the very few sightings ever made near the mainland of the United States. Later, we saw Hawaiian petrels twice again, but we could not be sure if it was the same bird or not. It didn't matter, Shearwater said. It was three sightings. Not long afterwards, we got the Xantus's murrelet, which caused about the same level of excitement. I spotted a black fin in the water and Debi Shearwater said it was a huge shark. "It must be ten feet long," she said. The skipper told us it was a salmon shark. I went back to the cabin. The cowbird had flown into the head, and I caught it there. It bit me, of course. I showed it to the other birders and asked whether we should put it in a box to make sure it got to land all right. "I think he's doing all right on his own," one of them said, so I let the bird go in the cabin, where he sat on a chair. We spent nine hours on the water and I got fourteen life listers off the boat, and seventeen for the trip with the three I got on the beach. When we were chugging back into the harbor, I suddenly remembered the cowbird and asked if it was still aboard. "No," one of the birders said with a smile. "When we got close to shore, he saw the land, flew off of the boat, and made a beeline for it. I was glad to be getting back to shore myself, and I was glad the cowbird made it back to where it belonged. BIRDS SEEN THAT DAY

1. Black-footed Albatross 08/08/2008 Open Ocean Northern California 2. Brown-headed Cowbird 08/08/2008 Open Ocean Northern California 3. Caspian Tern 08/08/2008 Open Ocean Northern California 4. Cassin's Auklet 08/08/2008 Open Ocean Northern California 5. Common Murre 08/08/2008 Open Ocean Northern California 6. Hawaiian Petrel 08/08/2008 Open Ocean Northern California 7. Heermann's Gull 08/08/2008 Open Ocean Northern California 8. Long-tailed Jaeger 08/08/2008 Open Ocean Northern California 9. Northern Fulmar 08/08/2008 Open Ocean Northern California 10. Parasitic Jaeger 08/08/2008 Open Ocean Northern California 11. Pink-footed Shearwater 08/08/2008 Open Ocean Northern California 12. Pomarine Jaeger 08/08/2008 Open Ocean Northern California 13. Red-necked Phalarope 08/08/2008 Open Ocean Northern California 14. Rhinoceros Auklet 08/08/2008 Open Ocean Northern California 15. Sabine's Gull 08/08/2008 Open Ocean Northern California 16. Sooty Shearwater 08/08/2008 Open Ocean Northern California 17. Western Gull 08/08/2008 Open Ocean Northern California 18. Xantus's Murrelet 08/08/2008 Open Ocean Northern California |