Go back to Memoirs and Essays Page

Places

Dash Inn Photos

TEEPEES

HOME

Search Site by Topic

Mariposa Hall, formerly the Sands Motel

Tacos Hot Dogs and Sausages

CHICO'S RESTAURANT

GASELE, WES B. December 6, 2018

Erstwhile Dash Inn Employee

Heyªªª, man. I came across your website of

photos and misc. of Dash Inn, and I really enjoyed it.

I worked there probably just shortly before you

worked there. I was there from August 1971 to

February or so of 1973. We more or less had the

same functions. I was a dishwasher for a year,

then prep. Chef, then assistant manager.

Thanks!

Wes (F/K/A Barnie)a

Frederic Beeson <flbeeson@aol.com>

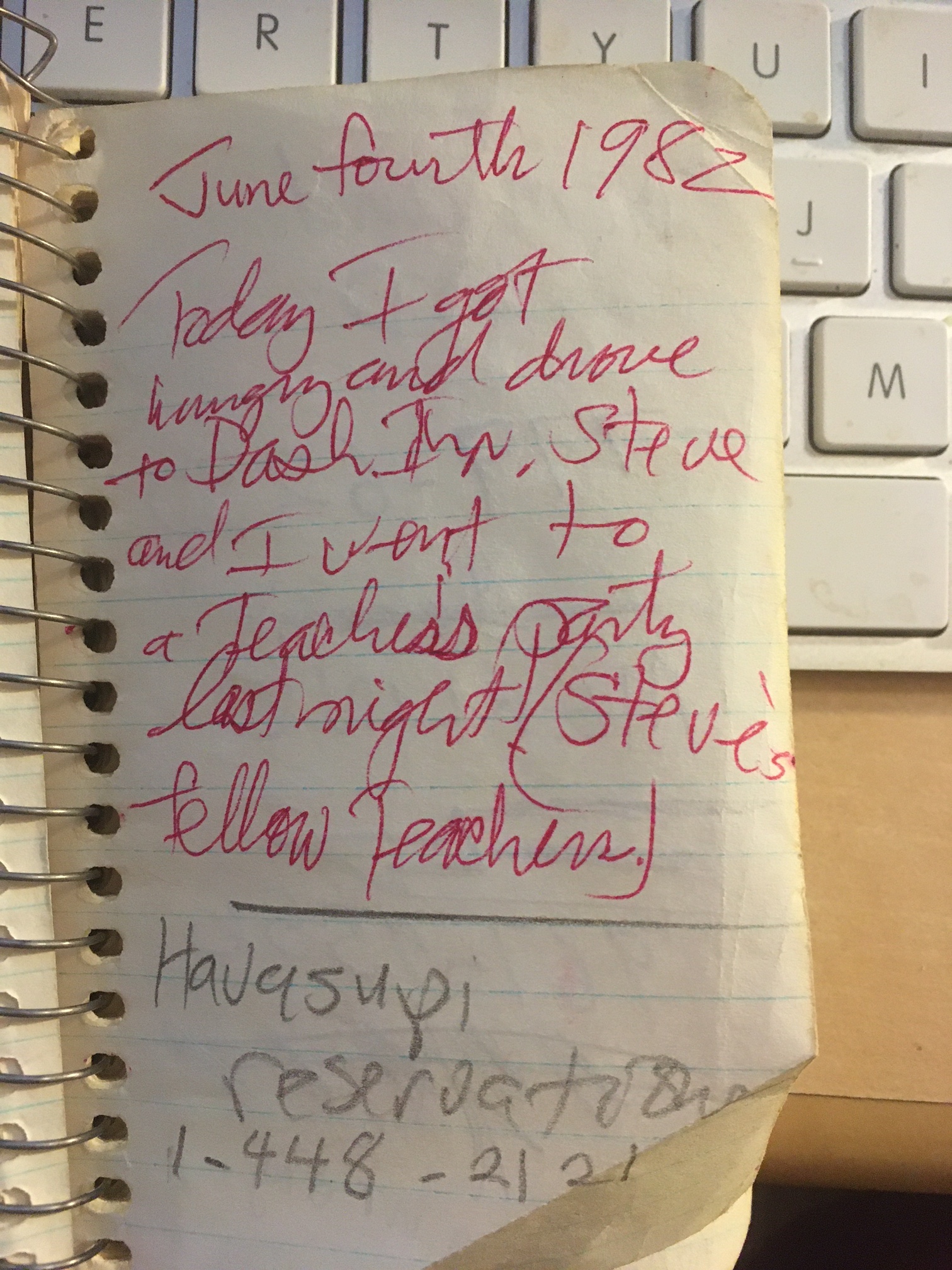

JULY 24, 2024ª

I

recently ran into your webpage concerning the Dash

Inn. Fascinating and nostalgic for me. I was hired

by Bill Swan to work there in 1971 and I worked

there until late 1975. First as

a dishwasher then I became a prep cook.

Later on I worked as Hash’s handyman at both the

Dash Inn and the second restaurant at Seventh

Street and Bethany Home. Mark Sharples was my best

friend from when were juniors at McClintock until he

passed away.

Wes “Barney” Gasele was and is still a dear friend of mine who I met at the Dash Inn. I have copied him on this email.

July 30, 2024

Frederic,

a

dashinnTeepees.jpg

|

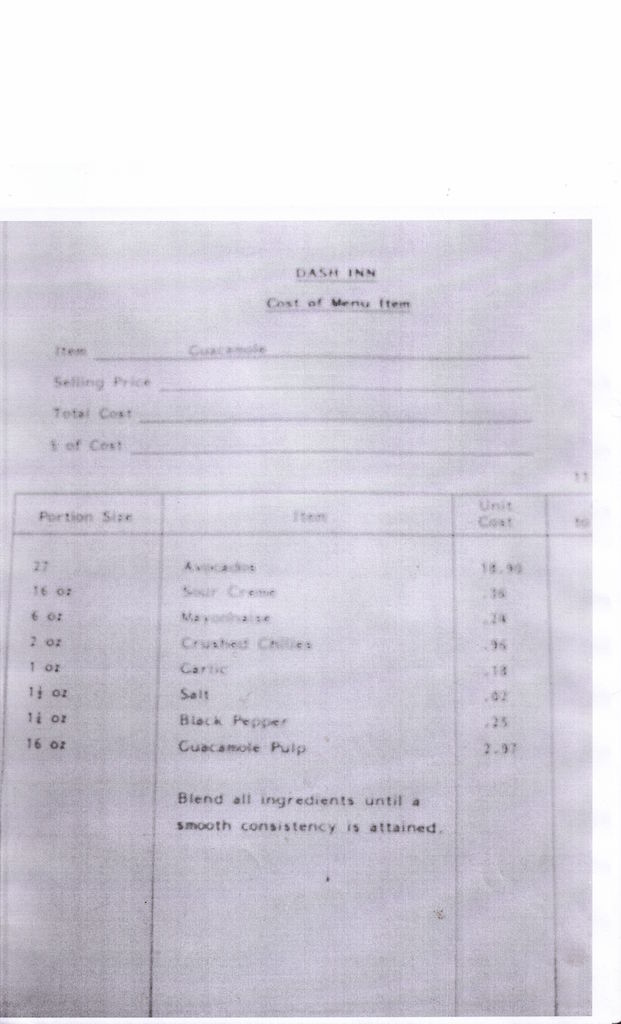

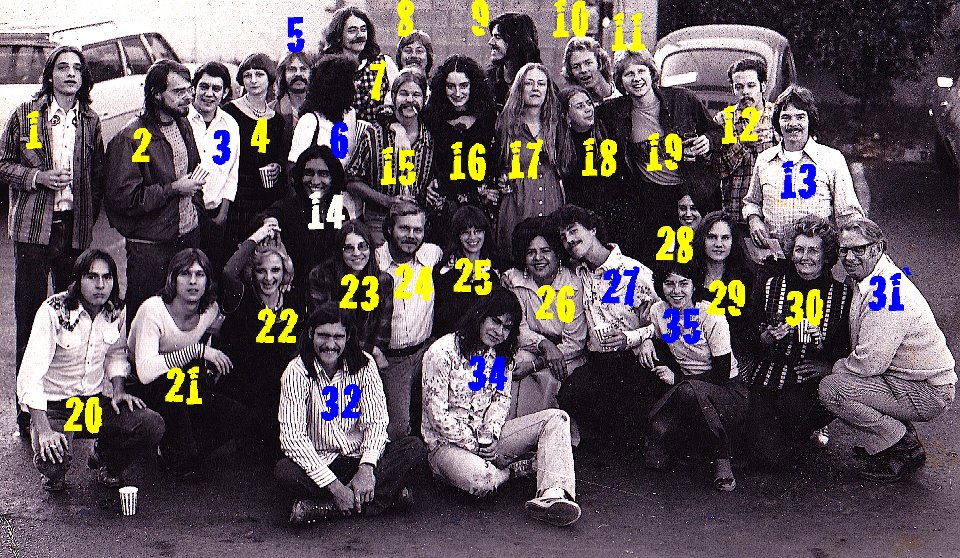

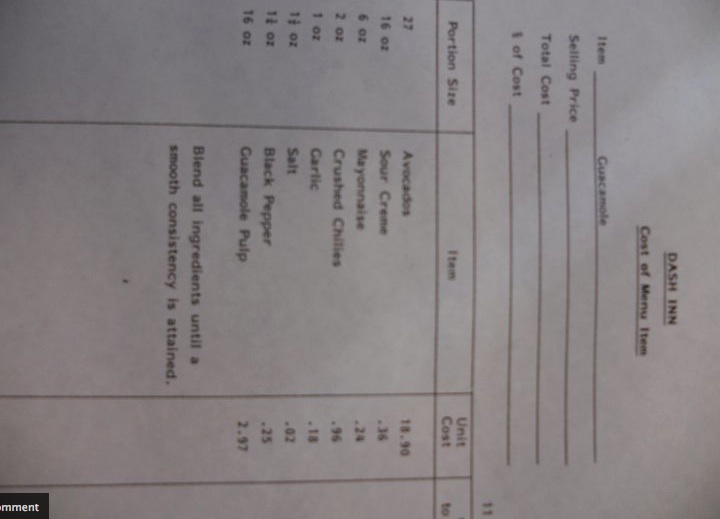

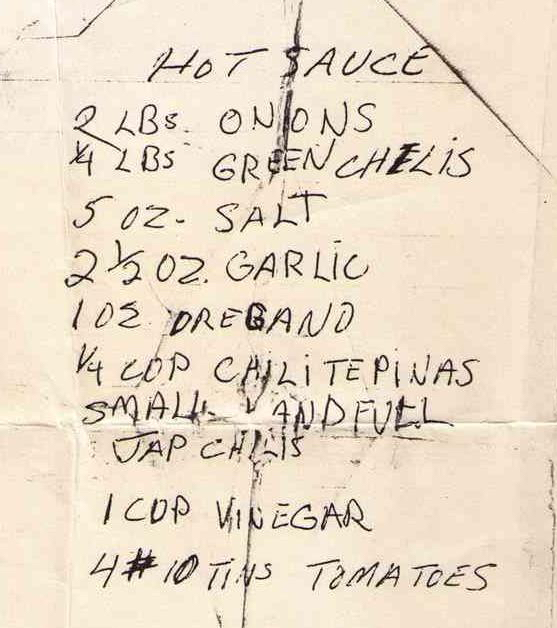

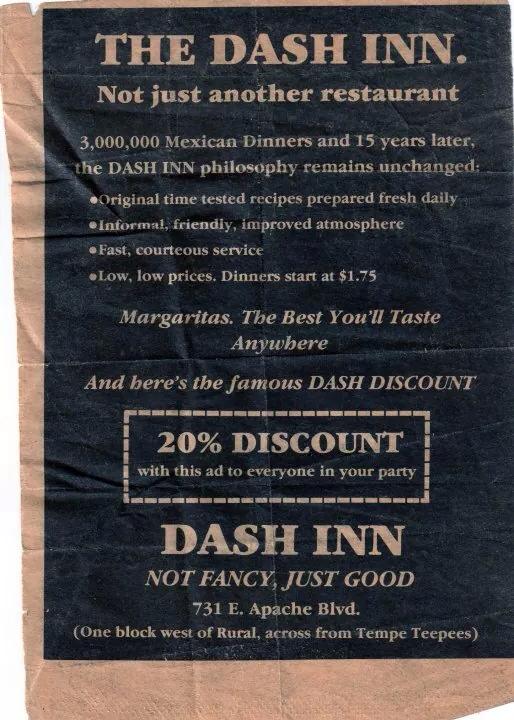

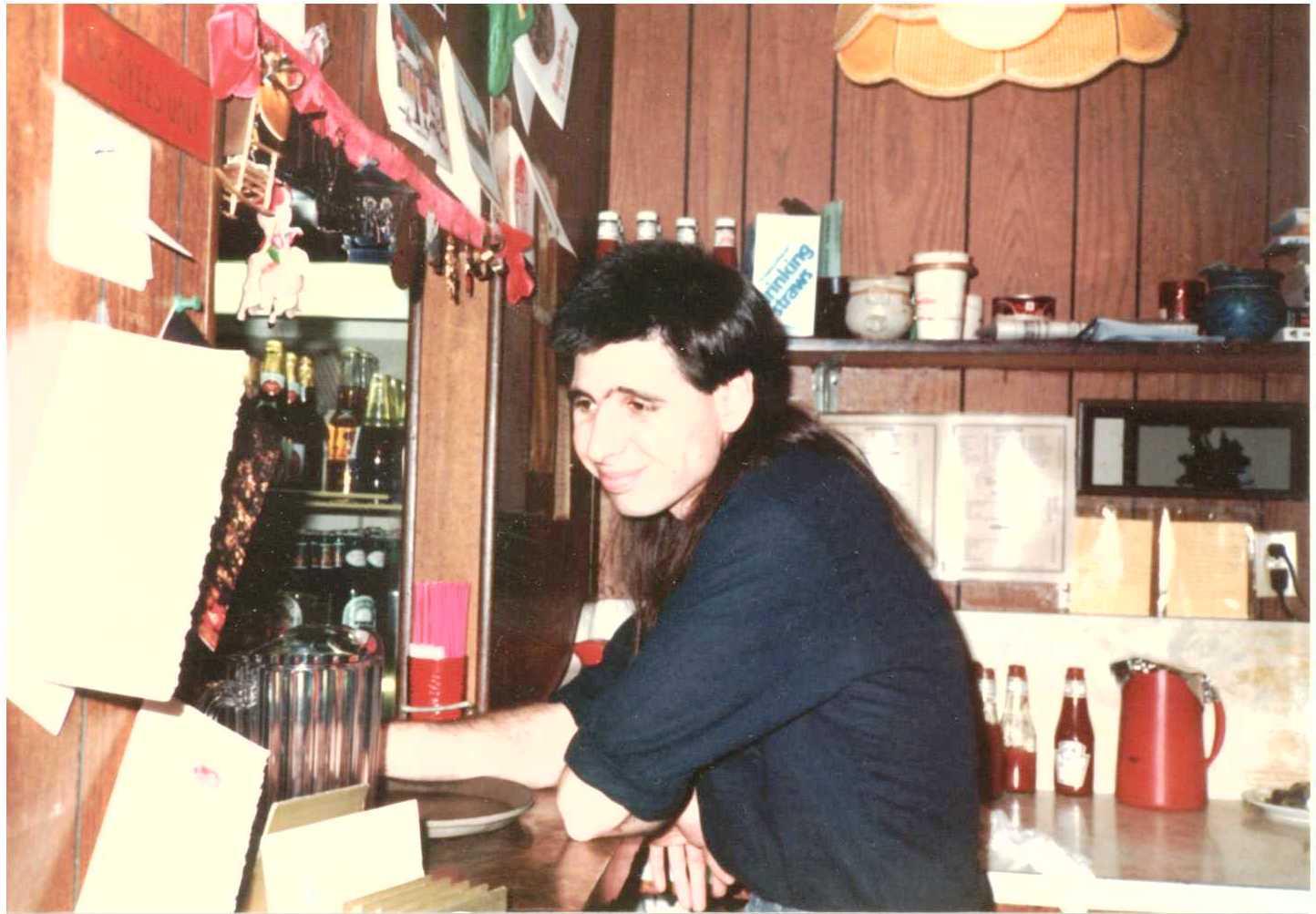

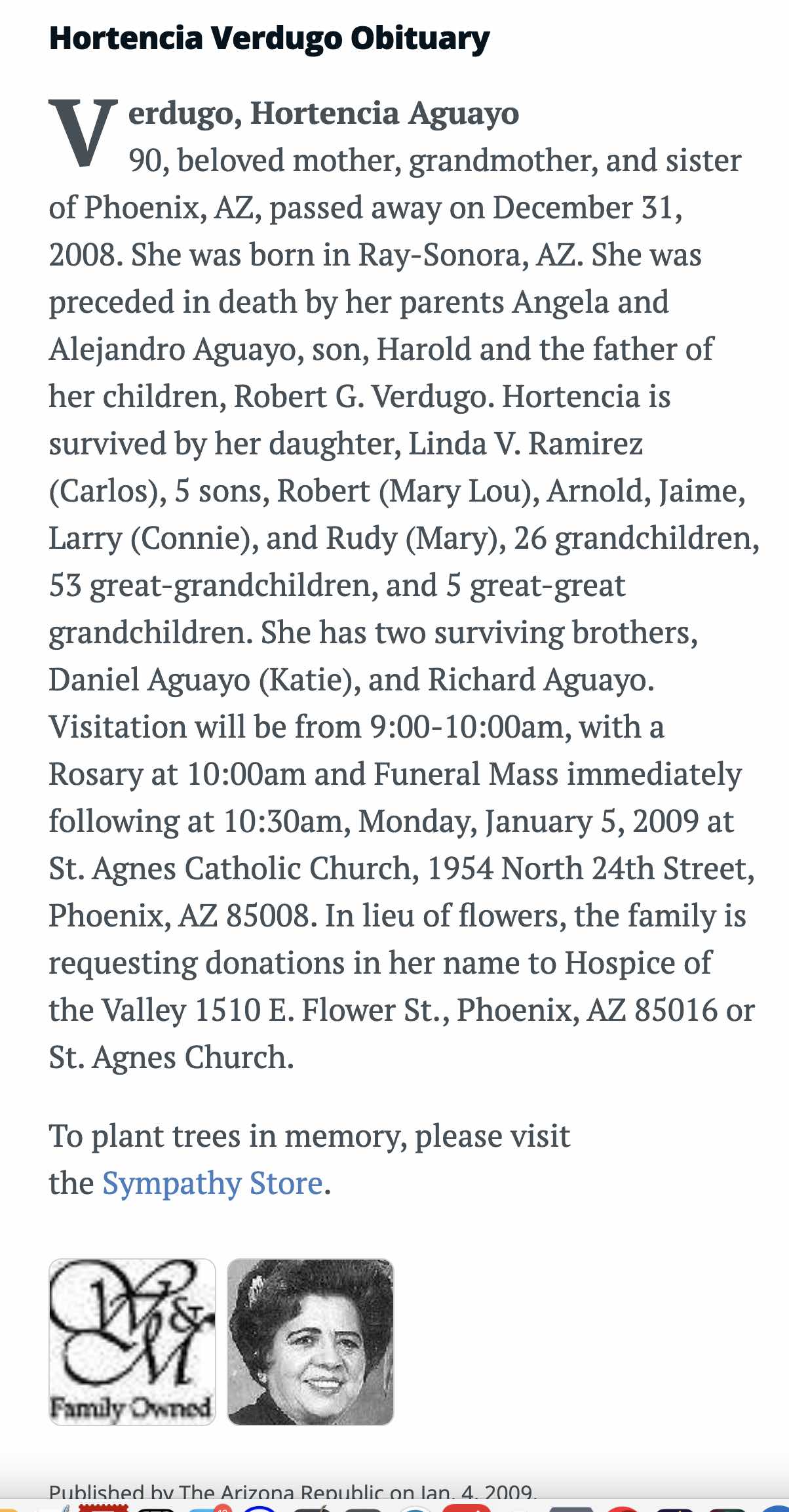

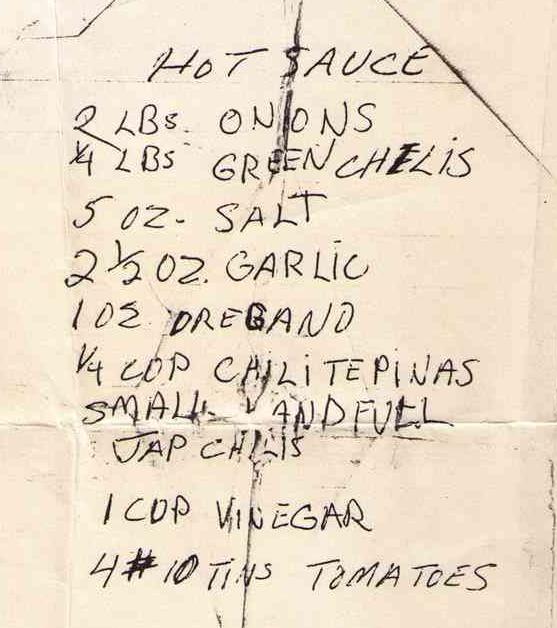

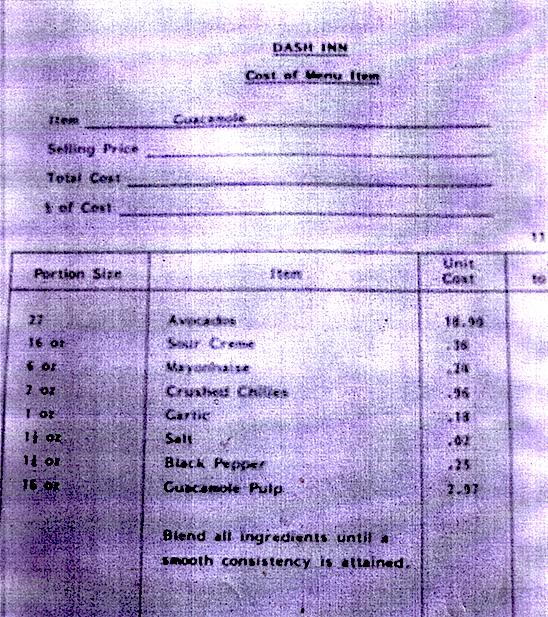

Simply Jumping—Hash Nelson—Prepping the Meat—Enchilada Sauce—Green Burro—Creamed Grass Clippings—Icky Sauce in a Metate Bowl—I Get a Job at Dash Inn!—$1.65 an Hour—Mamacita——Litrachoor—Naiveté—I was a Latch Key Kid—Gay Friend Falls for Tall Gal—Happy and Gay—Unwise Use of Plastic Buckets—Sadistic Dentist—Dinner for Two—I Storm out in a Snit!—¿Qué Pasa?—Facebook Fans Dash Inn was the only restaurant I ever gave a damn about and I still mourn its passing. The place got its name from its owners Hash and Dee Nelson, who combined their first names to come up with "Dash" and then added "Inn." Dash Inn was a local favorite restaurant in Tempe for better than twenty-five years. Everyone who was anybody went there. There were a number of reasons why Dash Inn had a loyal following. For one thing, it was right next to the campus, so it got a solid college clientele. But its locale was hardly the only reason for its success. In fact, the location was a loser for most other restaurants. Right across the street was a swath of land that had served as home to a number of different eateries, every one of which went bust in very short order. And even the franchise "Hobo Joe's" next door, seemed slow to dead while Dash Inn was simply jumping with action twenty feet away. Dash Inn was a hip joint, and you could see that just by walking in. Hash didn't give long-haired waiters a hard time when they applied for work; he hired them and just made them wear a pony tail the way the waitresses did. This gave the personnel and restaurant a look that attracted the counter culture while its traditional Mexican restaurant format brought in everyone else. Dash Inn's ambiance was definitely a key factor in its success, and so was its food. Nobody frequents a place just for the vibes; Dash Inn had a number of dishes that kept people coming back. The restaurant's slogan: "Not Fancy; Just Good" described them perfectly. Many of the items on the menu revolved around a salty and spicy ground beef that went in the tacos and burros and enchiladas. The cooks came in to prep at 8:00 AM every day to get that oily meat ready for the steam cabinets from which it would be dolloped out, and, of course, to prep the enchiladas and all the rest of the food that needed to be made ready. The enchilada sauce was a miracle. At first taste, it seemed vulgar and poorly conceived in the culinary sense. But if you ate an enchilada-style beef burro, you'd be tasting that sauce for the rest of the day in an eructive series of pleasures that let you know that you'd be back again—soon. The green burro was much the same. Smooth and savory, it grew on your mind the next day and made you want another—the way you watch a movie like Amadeus, say "Eh, well maybe," and the next day just have to see it again. I always fancied I could detect in the green burro a hint of cinnamon, which I didn't otherwise much like and which wasn't in the recipe. Perhaps it was the slightly toasted area of the flour tortilla that made it smell that way. In any case, the flavor of the green burro was so delicate that I never ordered one enchilada style, although lots of other people did. The guacamole was described by my brother as "creamed grass clippings," a portrayal that sounds depreciative, but wasn't meant that way. Indeed, his words describe the perfect guacamole: what should guac be, after all, but cool and green, and creamy with the flavor of your family memories steeped in the scent of Bermuda grass? Yes, people came to Dash Inn just for the guac the way the musically deaf bought Rubber Soul just for the one song "Run for Your Life." One of the finest culinary creations of all time was the Dash Inn Mexican pizza. It was nothing more than a corn tostado shell with that ground meat piled on it and topped with grated longhorn. It was heated in the oven and garnished with diced tomatoes and canned green Anaheims. The Mexican pizza and the green burro turned casual diners into regulars. I was, and still am today, an aficionado of the hot sauce made for the table in Mexican restaurants. I don't care much for the salsa-type sauces, the cold squashed tomato stuff with some chopped onion and a sprinkle of cilantro—you know, the sauces they serve up at a tooth-cracking temperature in a metate-like bowl made of fake black basalt. They're cold and stale and, frankly, I'm always afraid they're being recycled to other customers after you leave. Those ingredients ain't cheap, after all. The good table sauces are the ones in the squirt bottle. They're creatively spiced with anything from oregano to winter savory, and they're often cooked, so they will suddenly "turn" and become real sauce. Sure, sure, they get recycled, but they're safe in the sanitary bottle and no one is going to be dipping their chips and greasy fingers into them and re-dipping and slobbering in the bottle or dropping in cigarette ashes. I don't eat anything that I know has been lying out in the open where every bum who walks by can breathe his cigar smoke and halitosis on it. The table sauce at Dash Inn was the good kind, and in addition it was unquestionably the perfect match for the rest of the cuisine. Hash didn't even fool with making any of that cold, unsanitary salsa at all. He knew what was what. Dash Inn became a way of life. After my family completed any fun activity, the next destination was Dash Inn. Often we went bird watching before going there. We would drive to Headlight Pond or the Verde River and bird until early afternoon. Then we would toast our adventure over a pitcher of beer and the food at Dash Inn. That dining would end the day's productivity as everyone would fall asleep when we got home at around 3:00 PM. For years, going to Dash Inn was the source of great happiness for everyone I knew. You could relax there and have fun. You knew the waitresses. The place had a beer and wine license. You could run into people there. It was as though you lived in a New York borough where everyone knew everyone else, and there was a sense of community. In 1973, I graduated from college unskilled and with no ideas for the future. I returned to Tempe, got up my courage, and asked a waitress if she could put in a good word for me with Hash. I felt great when I saw how happy she seemed to be. She rushed over and talked to him, and I had a job—just as a dishwasher—but I was in and officially a part of it all. I worked from 8:00 to 5:00 and at the end of the second week Andy, the manager came up and gave me my check. He said, "You'll see I gave you $1.65 an hour instead of just $1.60 because you didn't goof off." That was $13.20 a day. I discussed the pay with the guys in the kitchen and we all concluded that it wasn't much, but you could live on it. Business was good. I once overheard Hash saying, I thought it was slow last night, but we brought in $300. Dash Inn didn't open until 11:00 AM, so at 8:00 I had no dishes to wash. Thus, I did prep work before the customers came. One job was grating the cheese. There was a back room with a big steel cheese grater and I had to stuff chunks of longhorn cheddar into it and fill white plastic buckets. The work had absolutely no entertainment value. I had to cut up the tortillas for the chips as well. I worked with Mamacita, the main daytime cook. Her real name was Hortencia Verdugo. She had been there forever and told me that she had to go home and cook for her "sans" after she finished at Dash Inn. Everyone loved her. One waiter told me that Mamacita told him she only read the National Inquirer because "The other newspapers do not tell you the truth." Hortencia Verdugo.jpg

Hortencia Verdugo

Mamacita Obituary.jpg

She helped me with

my Spanish and would always say, "No me

molestes, mosquito." if she were annoyed with

me. It was a line from a Mexican song. I

remember her saying to me once, "I tell you

Tomás, this Dash Inn. Year after year. It's

the same goddamn shit." It's funny how after

34 years I'm am sure that this is a direct

quote. She also once said these exact words:

"You all need a place where you can drink and

smoke and cuss."That place was the unused apartment that was attached to the back of the building. I thought it was strange that the nice apartment lay unoccupied back there. When I climbed the ladder and became a waiter, I was glad after a hard night to be able to have a place to drink with the waitresses and waiters. There were other characters there that I remember with the same recollection of conversation as clear as if the words had been spoken yesterday. One guy was a cook named Doug. I asked him if he ever ate the food and he said, "No, I don't eat this dog food," as he covered an enchilada with sauce on a plate that he put in the oven. He slammed the oven door. "It's shit." He often liked to say, "I'll make someone a good husband—or a good wife." He made a lot of gay references because he was what people would later call a flamer. Just the same he got married one day and It wasn't long before he was confiding in me, "Tom, the other day she says to me, 'I want to go out with other guys!' I say, 'Honey, we're married. So she brings this clown home. His wry, sour way of telling stories was really funny. Lloyd Thomas was the one I saw consoling him when she ran off with another man. "As far as I'm concerned, we're divorced!" Doug complained. "Well, relax. Stay cool. Drink your beer..." said Lloyd. I remember more of Lloyd’s words. He was crazy about big Russian novels. Someone came by and gave him a hardback by Someski about a foot thick, and he said, "Oh, thank you! This is going to be suuuuuuch a pleasure." I make fun, but I rather admired him for reading such big books. Once when I told him I had written a science fiction novel, he replied in the most softly pensive and serious way, "I tried to write a novel once. But I had to stop. I found... I found that it interfered with...with the ... the poetic techniques that I've developed... over the years." My brother was there when he said this, and we both agreed that on this one he was pretty much full of it. My good friend Brian became a waiter as I did and when he came on, he met Donna, a tall, dark-haired waitress that he instantly fell head over heels for. I was kicking myself for not foreseeing this. I asked myself why I hadn't told him beforehand that he was going to meet this terrific girl as though anyone could foretell who would fall for whom. She was all right and a bit of a free spirit. I went to her house, and I remember that there was a huge picture of her topless above the piano. I think it was a piano. It was just an artsy photo. Nothing dirty, though it seemed a bit bold to me. I look back on my thinking then and wonder about myself. Why would I have imagined that I could foretell my friend's attraction to her—especially when I knew full well that he didn't even like girls? Or did I really even know that? Naiveté. That was what defined me at the time and when I think of Dash Inn, that's what I often remember. Years before, when Goldfinger was released, the producers were able to have a character named Pussy Galore not because the times were modern or that mores were changing, but because of naiveté. People would hear the name and say, "Well, come on. They can't mean that!" That's how they got away with it. Such was my naiveté. When I quit Dash Inn, I had saved a ton of money and went to Europe. I remember walking in a red light district of Munich and seeing these painted ladies in windows along the street. I said to myself, "Jesus Christ, what slutty-looking women. If I didn't know better, I would swear they were prostitutes!" How could this be? I was a latch key kid. My parents were quite worldly atheists at a time when just saying the word would get you fired. My mother was special kind of rebel, a no-nonsense former WWII fighter pilot in the WASPS, who had absolutely no hang-ups. She had a wonderfully tolerant and progressive viewpoint and her politics were slightly to the left of Leon Trotsky. She wanted to make sure that I was never frustrated or inhibited. We were unconventional, and quite wholesome, mostly. Just the same, while other teenagers worried about sneaking girls into the house, I was encouraged to do so. I had no rules imposed on me, I hung out with the wilder crowd, and was the object of what my sisters now call benign neglect. So how could I have been so unstreetwise? We had a company party at Dash Inn, which was really happily anticipated because we got to close the restaurant and had the whole place to ourselves. Brian had had a falling out with Donna, and there was a dishwasher about our age named Carlos. He was a Yaqui. The Dash Inn party took up most of the afternoon. When it was time to leave, I went into the kitchen to get Brian and found him smooching with Carlos. "Let's go," I said. Brian tore himself away from Carlos, and we walked back to my house, where my mother asked Brian, "Well, was the party happy and gay?" Brian smiled and said exuberantly, "It was both happy AND gay!" I wasn't just naive about my friend's sexual orientation. I was naive about everything. Take the plastic buckets in the restaurant. I was naive about them too. I studied the system of food preparation at Dash Inn and noticed that it revolved around the use of these buckets. Some had holes cut in them and were used as colanders and set inside other buckets that caught the water that drained from the washed lettuce. Others were used for multi-gallon batches of hot sauce and still others to store the unfinished food in the refrigerator for the next day. I had a keen eye for business practicality and prudent practices. I felt that such dependence on these buckets was unwise. What if something happened to the buckets? A theft. A fire. What would you do then? It would take you forever to scare up a new set of these buckets. Obviously they had once been used to hold lard or some other product. How long would it take you to use up enough lard to have a complete set of buckets again? Answer me that! Oh, they were living right on the edge with this ill-advised bucket dependency. By God, the fools had put the whole goddamned business at risk. It never occurred to me that such buckets might be manufactured and sold separately—without any lard in them at all. It never crossed my mind that whenever he felt like it, Hash could drive down to some depot somewhere and buy as many of these stupid buckets as he wanted. Naive? I could tell you stories! When I was a child, my sisters must have known what a sucker I was. They told me of a magical place where I was going to go. It was filled with extraordinary marvels and all kinds of wondrous things to see and do. "AND," they said, "The FISH jump up and give you balloons!" I couldn't wait. They didn't tell me I was going to the dentist or that the dentist's name was Pat LeDan and that he didn't have any Novocain and that the sound of his drill alone could make people rise clean out of the chair and that he drilled holes to fill imaginary cavities in your baby teeth. I had to get into that dentist's chair on numerous occasions afterwards—but only after the adults were able to pry me out from under the table in the waiting room. Yet even after Pat LeDan, I remained naive. My father and I went to Dash Inn sometime in the mid seventies, and Hash greeted us. He said, "I'm opening a new restaurant in Glendale. It's called ¿Qué Pasa?" He got out a piece of paper and wrote on it, "Dinner for Two" and signed it "Hash Nelson." My dad put it in his wallet, but we never drove out there. Glendale was much too far away. The years passed, and Hash sold the restaurant, but the place kept the same recipes. Lloyd Thomas and some of the others I knew worked there for a decade more. One day I went in and found that the place had changed owners again and that the bastards had scrapped the menu. I was enraged. "We have a pretty respectable taco," the waiter told me. I gave him a ferocious glare. I hated him, and I got up and stormed out in a snit. I never came back. Later the university got its talons on the property and they bulldozed the building.

***

Twenty-five years passed, and I often thought of the restaurant in Glendale. I constantly longed for Dash Inn food and finally one day, it came to me on a flaming pie that it might just be possible to drive over there and eat. It was a crazy idea, but I somehow I thought it just might work. I got up one Saturday morning in 2000 and drove all of the way to Glendale to dine at ¿Qué Pasa?, and I loved the place. They had a more polished steel look than the old Dash Inn, but the decor was unlike any other place: there was lavender everywhere and the furniture had a sturdy fifties retro shape and form that I had seen nowhere else. The dark ceiling was covered with tiny lights to give the impression of being under the stars. I swear they had the same beat-up white porcelain plates. And the food was exactly the same. The only casualty was the creamed lawn clippings. I grieved for the departed guacamole, but I was grateful for the miracle that the rest of the entrees yet lived. A couple of years later, I was attending a conference at AGSIM, the American Graduate School of International Management. It was right next to ¿Qué Pasa?, so I got my co-workers to come with me for lunch there. Only we couldn't find it. It was gone. The building was empty. We wound up eating at some lousy chicken place.

***

I spend time occasionally now googling Dash Inn and ¿Qué Pasa? hoping to find that someone has opened a restaurant to bring those magical dishes back to life. But all I find is the defunct phone number of the Glendale restaurant and a reference made by some other old-time diner who speaks of Dash Inn in his blog. I emailed him and he didn’t do a careful job of reading apparently, for he quoted me as saying, "A cyber friend tells me that Hash is still doing great and runs a restaurant to this day in Glendale with the same tasty dishes!" I ignore his error and google Dash Inn. Defunct 20 years, the restaurant has more than 1,800 Facebook fans. |