Tom Cole

Old Memoirs Page

New Memoirs Page

Back to Home Page

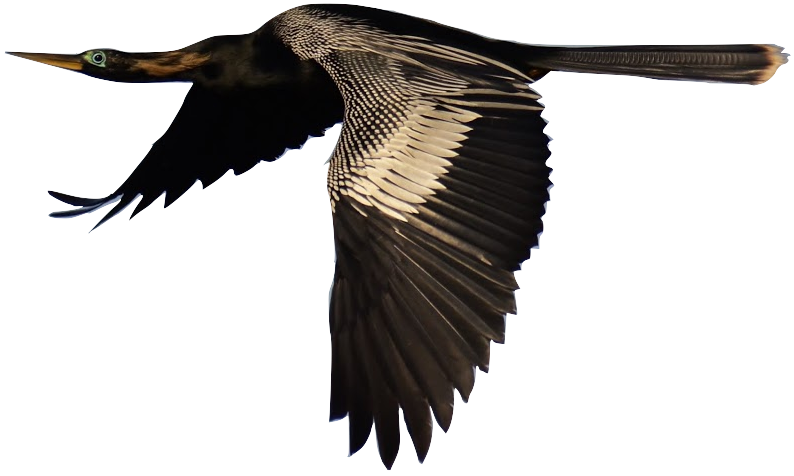

Anhinga Transparent.png

anhinga n.

Any of a genus (Anhinga) of long-necked birds having a sharp, pointed bill and inhabiting swampy regions of tropical and subtropical America. Also called darter, snakebird, water turkey.

-- American Heritage Dictionary

Audubon Park in New Orleans is a sprawling stretch of greenery with a number of long ponds filled with waterfowl.

I sometimes fly to New Orleans to visit my sister Sally, and she and I go over to the park and walk and do some bird watching. We do more interesting things in New Orleans, of course. The bird watching isn't spectacular, but if you are from Arizona, there are at least three birds that you are not going to see at home but are sure to see there. They are the white ibis, the little blue heron, and the anhinga.

When I was there last time, the white ibis just sat and looked at me and the little blue heron did nothing more than walk around gingerly in the shallow water. I took a couple of snap shots. I was happy enough to see these birds but they did not provide me with as much to think about as the anhinga did.

Anhingas are large rather sloppily feathered birds who can often be seen perched upon posts or docks with their wings spread out in the sun. Anhingas, you see, have no oil glands to waterproof their feathers. They must frequently dry themselves in the sun or else they'd get waterlogged and sink to the bottom of the pond and drown. Well, I guess that they would anyway. The birds eat fish and the way they catch them impressed me when I last went to New Orleans.

The anhinga floats like an armful of wet laundry, its wings spread and its wide, multi-feathered archaeopteryx tail soggily half floating, half sinking behind it. Its head is submerged well below its body as the bird hunts in the underwater foliage.

The anhinga stiffens when it spears a fish, and then surfaces upright with that fish impaled and held high upon its dagger-like bill. The fish, often a tiny immature bluegill, quivers in agony and the anhinga faces a sudden difficulty -- an entanglement of kinds: the bird's bill is stuck, and stiffly so, through the body of the fish and is therefore securely fastened shut. The bill cannot open to swallow the fish -- not with the fish itself impaled upon it. So the anhinga must take action to remove the fish and retrieve and eat it. Here's what it does:

The anhinga lowers the fish and then whips its head upward -- a expertly executed movement -- to fling and dislodge the bluegill from its bill. The bluegill flies upward -- directly upward, and then when the fish descends, the anhinga catches it in its mouth -- well, much of the time. Even the anhinga does not have perfect technique, and the fish sometimes falls slightly right or left or fore or aft of the bird's waiting bill so that it cannot be caught and devoured in a single toss. In such cases, the anhinga's deftly practiced bill bats the fish back in the air for another try -- and then another -- and another if need be, and the fish is repeatedly sent skyward until it sails directly toward zenith and then descends neatly into the open mouth of the anhinga. No seal in any circus ever balanced a ball on its nose with greater dexterity than the anhinga juggles a bluegill.

The anhinga has a reason to be good at juggling. If the fish fell back in the water, the anhinga would have but poor means to retrieve it. The bird, as its common name "water turkey" implies, is about as streamlined as a wet mop head and could scarcely pursue and respear the fish. No, the bluegill would dart, though mortally wounded, into the lake weed and die, and the bird would go hungry.

Still, the anhinga's strategy is an excellent one. If you have ever put on a mask and snorkel and lazily drifted beneath the surface of a shallow lake or pond into the weeds, you know that there are always plentiful fish there and somewhat curious and trusting fish at that. Gigging them with as nicely designed a spear as the anhinga's long neck and sharp bill would be a simple thing and if you were the bird, only a few minutes of work a day would provide you with more food than you could possibly digest -- this providing, of course, that you didn't wake up one morning with, say, a stiff neck.

Creatures in the wild must be pretty healthy to survive -- and ones with specialized strategies for procuring nourishment must be especially healthy because if any part of their system breaks down -- in this case, the sharp bill, the quick neck, the careful balancing act, etc. -- the animal cannot feed. Compare a kingfisher, which must hover and dive headfirst into the water to catch a fish, to a surface feeding duck. A bad head cold would put the kingfisher out of commission long enough to starve him while in the meantime the surface feeding duck might miserably dabble its way to good health and happier times. That's my theory anyway.

I'd rather be the kingfisher, or the anhinga because if you're healthy you're eating a lot better than any mallard that is sucking up scum and trying to filter it out for its edible content.

All of this brings us to part of the reason for one's watching birds. It is the vicarious pleasure one derives from watching whatever the animals do -- and while the vicarious pleasure for some might be watching them fly or do a hundred other things, what more vicarious a pleasure is there than one that deals with food? This is the reason I prefer diving ducks to the dabblers. The divers eat mollusks, and the dabblers -- well, who can say? I like sardines and smoked oysters and so naturally my sympathetic nature reaches out more to diving ducks and American Oystercatchers, who do what their name implies, and even with birds such as dowitchers and snipes who probe for worms with their long bills -- even though I don't eat very many worms.

But I digress. My contention at the end of all this is that since there is not room for such information in common bird guides, a special edition should be produced that shows in detail what each bird eats and how he goes about it. It'd sell big -- especially if it were set up like a regular familiar field guide and included other fascinating facts about each bird. The traditional field guide concentrates mainly on identification. There may be descriptions or even illustratons of behavior or habitat, but these are principally to aid the bird watcher in determining what bird has been seen. The guide I propose would simply add to everyone's knowledge of each species and increase bird appreciation.

Therefore, instead of the typical citation in the guide:

ANHINGA

Common in fresh-water swamps, ponds, and lakes, where it spears fish. Often swims with only head and neck exposed. Long straight bill, long tail and white wing and back plumes differentiate it from cormorants. Usually seen singly, but may soar very high in flocks.

I propose:

ANHINGA

Also called darter, snakebird, water turkey. Life span: 3 to 5 years. Mates for life and male takes turn incubating eggs in the floating nest. Spears fish in shallow water and does an amazing juggling act when it flips them from its bill into the air to be caught and swallowed. Eats from 12 to twenty bluegills a day and supplements its diet with lake weed. Anhingas are unsafe to handle as their sharp bill can poke out an eye. Resembles an armload of laundry floating in the water. Produces no water repellent oil and will sink to the bottom of the lake and drown if its feathers are not dried frequently. Not generally considered edible, but poor people on the Bayou report that it tastes a great deal like chicken.*

*Many of these facts are for the purpose of argument only and are not scientifically accurate.