Go back to Memoirs and Essays Page

Go to Pigeon Related Photos

Go back to Tom's Home Page

BIRD LINKS

HEAR LUCKY COOING CLICK HERE

Twizzie, the World's Greatest Pigeon

Pigeon Fanciers, an Essay

Lousy

Records—a Single Egg—Dumping at the Zoo—The Pigeon

Net—Twizzie—Rollers—The

Irrigation Man’s Truck—A Gentle Soul

Lucky's feather

Lucky's feather

This story has no ending—at least it won't until Lucky dies. But he just keeps on living and living. All of the other pigeons in the old coop have been dead ten, twenty years, and I've long given up raising birds though I've still got Lucky. He's half white and half what we call ash-red. His feet don't work well though he can stand and waddle a bit. But I can fly a lot better than he can now. He just sits there in the little cage on the kitchen floor. Sometimes he coos. Sometimes he growls. Mostly he just sits there. Out in the back yard is the old, empty pigeon coop. We used to write notes in pencil on the back of the coop whenever a pigeon hatched. It was a lousy record system; the boards weathered and the writing faded and finally vanished entirely, so I don't know Lucky's exact date of hatch. But he's twenty-three years old if he's a day.

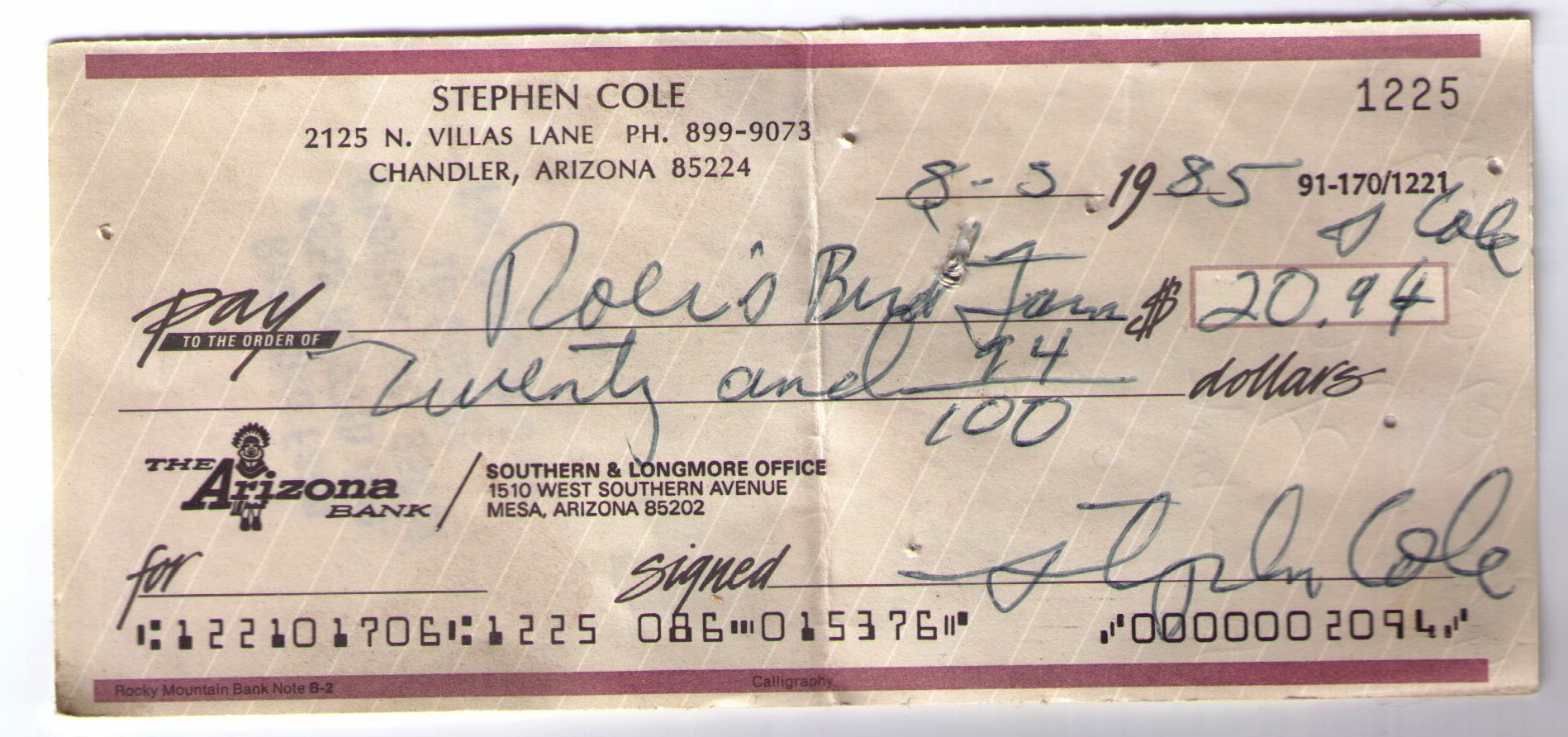

Pinned to my kitchen bulletin board is my brother's cancelled check for $20.94. It is dated August 3, 1985 and made out to "Roer's Bird Farm." That was the check he and I used to buy Lucky's parents along with another pair or two. I tend to keep things: old checks, my baby teeth, Lucky.

We had the worst time getting those birds to breed. The eggs wouldn't hatch, and we tossed them out well before the 21-day gestation period was over as they were obviously rotten. But finally, Speckles, Lucky's mother, laid a single egg that actually hatched and we named the squab Lucky.

Afterwards, the pigeons reproduced like crazy, and the coop would get so full that we'd take thirty or so at a time down to the zoo and let them go. We never got rid of Lucky because he was the first to hatch. There were lots of other pigeons to which we had sentimental attachment, and they stayed home too: Squeaky, Mohawk, Cielito.

The zoo was not really the best place for the birds we exiled, but it was far enough away that they wouldn't fly back home like racing homers.

We really thought they stood a fighting chance of eking out a living at the zoo or we wouldn't have dumped them there. And we didn't look upon their banishment as certain death even though we knew the zookeepers had a big "pigeon net." They would sometimes throw it across a couple of hundred feeding pigeons at a time and then serve the birds they caught to the wildcats and other animals that needed fresh meat.

We used to fly our pigeons in those days. They would "kit up" in a group and fly straight above the house so high that we could hardly see them. Then, being rollers, they would roll. Well, not Lucky. He wasn't such a good roller.

I said that we were fond of some of the birds and over the years the one to which I had the greatest sentimental attachment was Twizzie. I had him when I was eight or nine years old and kept him in a different coop in the backyard of a different house long before the days of Lucky, and Speckles, and Cielito.

Twizzie was a gentle soul and the best pigeon I ever owned. I named him Twizzie because he didn't roll but twizzled, did back flips instead of rolling. Twizzie, like Lucky, was a roller and as such was supposed to fly to good altitude and roll backwards straight down thirty feet or more and recover. The deep rolling breeds, the Birmingham or Pensom rollers did just that, but it was also a hazardous habit because if a bird rolled too far, it would hit the ground and die. Twizzie's mate, a blue check hen, hit the roof of our house on a roll and was knocked out cold. We put her in a recovery cage, and she finally woke up and was put back in the coop. She survived for many years, but never rolled again. Ever.

I used to take Twizzie to school with me and release him out on the playground. He'd circle and do back flips before heading home with the flash of his white wing tips contrasting against his dark body. Sometimes I'd go out for recess and see him high up in the sky flying and doing flips. I loved everything about Twizzie—even his coo was the perfect pigeon coo: Guadalupe, Guadalupe...

Twizzie got run over by the irrigation man's truck. It came as a blow to me. As I said, Twizzie was a gentle soul and the best pigeon I ever owned.

Mating For Life—A Population Drop—Painted on Their Perches—Dreams of Flight—Squeaky and Chalky—The Mausoleum—Vladimir Lenin

Pigeons mate for life, but they are still a little promiscuous, and if their mate is gone any time at all, they quickly mate for life again. Lucky's mate of many years died and he then said, "I do" to Speckles, who was his mother, but what do pigeons know or care? He sired countless offspring that either died of old age, wound up getting fed to wildcats, or flew the coop some other way.

Playing host to all of these pigeons became tiresome over the years, and so I kept my favorites, and in time they became infertile, and the population began to drop in the coop as they died. I never did let them out to fly again.

I remember seeing two of them, Columbus and Cielito year after year sitting still upon their perches as though painted there. They rarely moved. It gave me a pang of guilt every time I looked at them.

But I was always able to solace myself with the memory of what happened to a rough and tumble old street pigeon I invited to the coop. He became the cock o' the walk immediately and loved the place. In the coop, he had a social life, three squares, and no cat trouble. I once tried to throw him out of the coop, and he flew back and clung to the chicken wire, desperate to be caged again. I gave him his wish.

Pigeons love the coop, but still I wondered if these old birds sometimes dreamed of flying once more. Somehow, I'm sorry to say, I believe they always did. How could they not?

Squeaky was a petite blue bar roller with splashes of white on her face. I was fond of her, and she fell into a very elite group of pigeons along with Twizzie and one old cull I remember named Chalky. They were special because they were so obviously smarter than all of the other pigeons. They'd trick you when you'd open the door and make a break for it, getting right past you and taking to the sky. Squeaky did this quite often and I would shout, "Get back here, Squeaky!" And wouldn't you know it, Squeaky would fly back and dive right through the door again and alight on her perch. She knew exactly what I said—or so it seemed at least to me.

Squeaky got sick and died, and I froze her in the refrigerator, which has become something of a pigeon mausoleum. As I said, I tend to keep things, and for those who think this is a strange habit, I point out that Vladimir Lenin has been lying in state wearing the same cheap suit for close to a hundred years with (as far as I know) no refrigeration at all, and people wait in line just to see.

Chuckles—Pecking—Darwin’s

Pigeons—Mendel—Genetics—Neo

Professors—The Dilute Gene

One day, more than ten years ago, Chuckles came to the coop. One of the women at work had a pigeon and she asked me if I would adopt it, and I did, and I regretted it.

You see, Chuckles brought with her a kind of vileness and wickedness that I don't remember seeing very often in a coop. Oh, the coop can be plenty tough even without a bird like Chuckles. The walls at the floor of the coop, for example, should always have a kind of running board, a wooden skirt a few inches above the floor, so any squabs that might happen to fall out of the nest can get under it and not be pecked to death. And yes, once, my brother was examining a squab and then accidentally put him into the wrong nest box, and the pair of birds living there pecked it until there was nothing but a pink skull cap showing. In the case of skull peckings, by the way, there was never an infection. The squab would slowly heal and skin would cover the bared bone. Afterwards, down would grow until perhaps three years later the adult bird would have a smoothly feathered head like a bird that had never been scalped at all.

Yes, there were some rough moments in the coop. Still, Chuckles was to bring with her a ferocity and meanness that I have rarely seen in a bird, especially a hen.

Now, Chuckles didn't come with a name. When my father saw the bird, he said, "Why don't you name him Charles Darwin?" Chuck for short. Well, I had a Columbus, so a historic name wasn't out of the question. We thought Chuck was a cock at first (You can only tell the gender by the bird's behavior.), so we didn't know we'd have to change the name to Chuckles, only slightly more feminine in sound. But I knew that Darwin was a good person to name a bird after, being as he was the most famous of all pigeon fanciers. In fact, he kicked off his first chapter of The Origins of Species with:

“Believing that it is always best to study some special group, I have, after deliberation, taken up domestic pigeons. I have kept every breed which I could purchase or obtain and have been most kindly favored with skins from several quarters of the world... Many treatises in different languages have been published on pigeons and some of them are very important, as being of considerable antiquity. I have associated with several eminent fanciers, and have been permitted to join two of the London Pigeon Clubs.”

They talk about Darwin's finches, but perhaps it was really his pigeons that are to credit for his insights. The pigeon was absolutely perfect for the development of Darwin's theory. He knew that the breeds of pigeon were so preposterously different in appearance that no sane person could place half of them in the same genus by their morphology alone—much less call them the same species. There were giant "runts" with three-foot wingspans, broken-necked fantails, sliver-thin tipplers, chicken-like modenas, pug-faced Chinese "owls," and falcon-winged Ukrainian sky cutters. And yet all scientists and fanciers universally agreed that they were all simply variations of the common rock dove, Columba livia—not because anyone knew a single thing about genetics at the time, but because they could all make babies together.

Darwin devised a wonderful experiment which perhaps is best to let him explain himself as he did in the first chapter of The Origin of Species:

I crossed some white fantails, which breed very true, with some black barbs—and so it happens that blue varieties of barbs are so rare that I never heard of an instance in England; and the mongrels were black, brown, and mottled. I also crossed a barb with a spot, which is a white bird with a red tail and red spot on the forehead, and which notoriously breeds very true; the mongrels were dusky and mottled. I then crossed one of the mongrel barb-fantails with a mongrel barb-spot, and they produced a bird of as beautiful and blue colour, with the white loins, double black wing bar, and barred and white-edged tail-feathers, as any wild-rock pigeon!

In short, the barb-spot-fantail mix reverted back to a classic blue bar street pigeon with no effort at selection on Darwin's part. It would be hard not to wonder how great a part this experiment may have played in Darwin's work on diversity and evolution.

Now, here we come to genetics, an advantage that contemporary breeders have over Darwin. Let me explain this advantage with the following story: there was a department head at a major university who was kind of deranged and used to hire only Baptist preachers to teach biology. This may sound like an outrageous claim, and it's one my father used to make, but consider this: my mom came up to me once and said, "Tom last night Jerry was introduced to a biology professor whose wife said he'd been hired by W.T. Wentworth. Jerry shouted, 'Well you must be a Baptist preacher!' and his wife said, 'Er... actually he is.' " Faux pas City, but my father couldn't have cared less, and it does show there was some truth to his claim.

At any rate, the story goes that these neo-professors would get up and have the undergraduates take notes as they said various things. One of the things they always said was "If Darwin had known about Gregor Mendel, he would never have developed his theory of evolution." The undergraduates would write these words down in their notebooks and carefully review them later. Then, there would be a test.

In actuality, though, Darwin would have loved to have known about his contemporary Mendel because he could have explained, in part, the problem people confronted him with regarding the selection of favored characteristics in plant and animal populations. People argued that advantageous genes of a particularly sturdy animal would simply find themselves awash in the run-of-the mill genes of its mate—diluted like watered-down whiskey generation after generation until there was no whiskey left at all, just a homeopathic remedy of some sort. There was no mechanism, they argued, to keep the favored characteristics from being very quickly winnowed away. I imagine Darwin might have replied to this with something like, "So you envision a system in which all the genes just average out and we are all stuck with the lowest common denominator—repeatedly. Well, that would appear to be true, but since this doesn't describe the real world, and I am obviously correct in this by all the evidence, we can only assume that there may be somewhere an Austrian monk named Gregor Mendel, whose fledgling science of genetics will begin to explain some of this with its dominant and recessive genes and so on."

Darwin would have liked Mendel's work for a better reason than that it upheld his theory; he would have liked it for the sheer fun it provides the pigeon fancier. For example, Darwin would have liked to know about the dilute gene that turned his blue birds to silver and his red ones to yellow. When Lucky hatched, we immediately knew by his thick coat of yellow down that he would not be a "dilute" with regard to color. Birds with the dilute gene hatch naked.

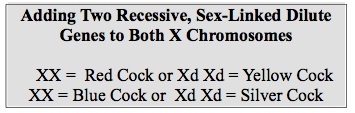

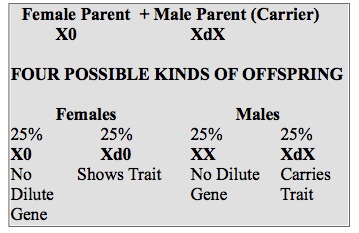

The dilute gene is recessive and sex linked. Pigeons have no Y chromosome, and the male has two X's and the female just one. I used to write a zero next to the female's single X for purposes of symmetry and clarity when I mapped things out: X0 is a hen, and XX is a cock. Since the dilute gene is recessive, a male will need two of them for the dilute color trait to show up in his appearance—his phenotype. The following chart shows how an otherwise XX red cock becomes diluted to a cool-looking yellow when the dilute gene (indicated by a little "d") is present on both X chromosomes, and how in the same way a blue cock becomes silver:

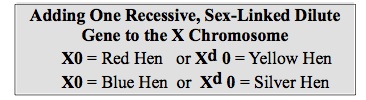

The female with a dilute gene always shows the trait in her phenotype because the recessive gene has only that zero to compete with it. Thus, using a zero to even things out for the missing Y chromosome, an otherwise X0 red hen becomes a cool-looking yellow bird when the dilute gene is present on the X chromosome, and a blue hen becomes silver.

Some males carry the trait but do not show it. In that case, if you cross a male carrier with a non-diluted female, you can sometimes know the sex of a squab the minute it hatches. It's easy. Any of their offspring that hatch naked will be females—and will show the dilute color trait when they grow feathers.

There's a world of genetics like this and breeders have fun mapping out whether the birds will be barred or checked or grizzled or whatever.

The Story of Chica, An

Unsettling tale—Nearly

Beheaded—Timeshare—Banishment—The Ants Always know

When Chuckles went into the coop, Lucky had no mate as Speckles had died, so Lucky and Chuckles paired up. By this time Lucky was infertile, and so Chuckles would lay infertile eggs, and I would end up breaking them after a time, and Chuckles would lay more. In a short time, the last of the other pigeons in the coop died, and Lucky and Chuckles had the place to themselves.

One day, I was driving home through a kind of run-down neighborhood and saw a pigeon with a broken wing. For some reason I stopped, picked him, up and put him in the car. The neighborhood was heavily Hispanic, so I named him Chico and later Chica when I found that he was a she.

Chica went into the coop and went on living. Years passed and one day I saw that Chuckles wouldn't allow Chica to eat. Chuckles had a new nest on the floor and that's where I threw the grain, so Chuckles was defending the whole floor as her nest. Chica, with her maimed wing, was no match for Chuckles, yet the trouble seemed to pass, and I soon forgot all about Chuckles' attacking Chica.

One day, I found Chica on the floor of the coop apparently dead. I picked her up and found she was breathing. I felt she was on her last legs, so I took her to the side yard and got a shovel to cut off her head, but I lost my nerve and called my brother. "Hey, Steve," I said. "Will you come over and cut this pigeon's head off? I can't stand to do it."

"No," he answered "Hell, no. Do it yourself."

I went back to Chica with the shovel and pressed it against her neck ready in an instant to slam it down and put her out of her misery. I tried again and again, but I couldn't force myself to do it. Finally, I chickened out entirely and got a little cage from behind the coop and put Chica in it. I put the cage and the bird in the kitchen. The next morning, Chica was standing up looking fine. It seemed almost miraculous. I put Chica back in the coop and came back a while later.

It was then I understood what had happened. There was Chuckles smashing away at Chica with wings and beak. Chica was in the corner of the coop, down for the count. I threw open the door in anger and grabbed at Chuckles. She roared and fought me, but I drove her away and picked up Chica. She was practically limp, but after another night in the kitchen cage, she had again miraculously rallied. And there in the kitchen she stayed until it occurred to me that Chica didn't deserve this banishment.

I picked up Chica, went to the coop, and said, "Oh, Chuckles! Let's do some time sharing." I put Chica in the coop and went after Chuckles. It was a noisy catch with a lot of slamming about, angry cooing, and a cloud of feathers in the end, but I finally had Chuckles in my hands and brought her into the kitchen. She struggled, but I threw her into the cage. Chuckles looked about, took in her surroundings, and made a decision. She then busted out of the cage—just flew at the swinging wire door on the top and bashed it clean open and went right out, flying through the house. She had the brains of Squeaky, but not the good-natured soul. It took me a half hour to catch her and get her back in the cage, which I secured with a heavy river rock on top.

The next day, Chica and Lucky were billing. They had mated for life, and I savored a little satisfaction at that and went right to the kitchen and said, "Oh, Chuckles. I've got something to tell you!"

As the days passed, I began to resent Chuckles more and more. I punished myself for my blindness to what had been going on—for how many years? Had poor Chica, odd hen out, been in a pigeon hell that I had unwittingly devised? How long had I let that evil and jealous hen torment her? Finally, I decided to get rid of Chuckles. I couldn't put her back in the coop, and how long could anyone go on with a pigeon living in their kitchen for goodness' sake?

I put the cage in my truck and drove to the university. Getting her out of the cage was a battle royal. I finally got a good hold of her, but she fought me almost breaking free. To keep her in my hands, I needed to use so much strength that I thought I would crush her. I turned from the truck and tossed her out on the campus grounds. She alighted and then flew away. She was the strongest, most ferocious pigeon I had ever seen.

The next day Chica lay on the floor. There were ants on her, so I knew she was dead. The ants always know. I put her in the freezer with Squeaky.

Lucky was alone.

And he got old. And he couldn't fly. So I put some bricks on the floor of the coop for him to sit on. And there he sat through the burning summers, and the freezing nights of winter.

A

Joke—Weather—Incompatible

Roommates—Seventy-five-Watt Bulb—Special Seeds—A

Night out under the Stars—Sierra Pond

Sierra Pond 2125b.jpg

Sierra Pond 2125b.jpg

A man goes to a psychiatrist and says, "Doc, I've got a problem. My wife keeps a nanny goat in the bedroom. It's a pet. Now, I've got nothing personal against nanny goats, but this one happens to smell to high heaven!

The psychiatrist asks, "If that's the problem, why don't you just open the window?

"Are you crazy?" says the man, "And let out all of my pigeons?"

I never thought I'd be the man in that story.

How the summer heat might affect the pigeons never concerned me very much though I live in Arizona, and the temperature has risen as high as 123 degrees. I knew that Mourning doves sit on their eggs in the summer and rather than warm the eggs, the birds keep the eggs from frying by evaporative cooling. The adult bird simply begins to dry up in the sun, and the slowing evaporating bird cools the eggs. So I knew that doves could stand the heat.

In 2005 my dog Noodles died, and in July of 2007 I had a dream about her. I dreamed that I had left her on the shore of Lake Itasca in Minnesota, and in the dream I realized what I had done and went and found her and told her would never leave her again. In the dream, I gave up my airline ticket to drive Noodles back to Arizona. And so a few days later as I was walking back from the local saloon through the blazing 115-degree Arizona day it hit me: Like in the dream, I had abandoned Lucky in the coop, and Lucky was too old to take the heat anymore. I wrote in my journal that night,

July 8 2007: When I got home, I took Lucky inside in the air conditioning into my room in a nice cage ....How could I have left him outside any longer when it is 115 degrees? I scratch him on the head, and he likes it. God forgive me for the time I have wasted.

LUCKY LOOKING GOOD 2005:

It was not to be as joyous a decision as I thought. I was soon to learn something about how Lucky viewed me and his world. This happened when I got it into my head to change the living arrangements. You see, I felt that the cage with its wire top gave Lucky an uncomfortable feeling of confinement. Outside, I had fastened a yard-square board atop a single post which I had embedded in a five-gallon can filled with cement. It was a bird feeder that I didn't use much, preferring instead to throw the seed on the ground for the Inca doves and other birds. If I brought it into my bedroom, Lucky could live on it. He couldn't fly, so if he didn't just fall off, it would be a perfect place for him.

I carried the heavy "table" in and tried it. Lucky fell off a couple of times, and I'd find him on the floor and put him back. But falling off was not the problem. The problem was that while in the past he tolerated me as a casual visitor to the coop, I had now become a permanent live-in. He used to allow me to pick him up and scratch him, and this agreeability I took to mean he liked me. I had mistaken toleration for affection. When I set him up to live in the bedroom, I learned that Lucky regarded me in an entirely different way. Now, I was not the occasional guest visiting briefly. Now, I was there to stay.

I would come into the bedroom, and Lucky would stiffen on the tabletop. He would growl and look up at me with the red eyes of a bull. He couldn't paw like a bull, but he did something I had never seen a pigeon do: he started batting, rapping his wing, where the bone met feather, onto the tabletop. The behavior was filled with aggression and perhaps even hatred. "Rappity rappity rap! " he was saying. "The creature visits itself upon me forever! The creature! Curses! Rappity rappity rap!"

Arizona winters are mild, but there are nights that freeze. On those nights, I always used to cover the coop with blankets so no icy draft would kill anybody. Now, Lucky was very old and sitting on the floor, so I ran an electrical wire out to the coop and plugged it to a metal desk lamp with a 60-watt bulb in it. I covered the lamp with tinfoil and put it just inches from where lucky would sleep at night. The blankets, of course, stayed. A little later, I swapped the bulb out for a 75-watter just to make things a little warmer. But it got to be a hassle, and now Lucky is back inside on the kitchen floor and has been for some time. And here he will stay.

His eyes have dried up and get stuck shut, but every day I pry the lids apart and put drugstore eye drops in, and the eyes seem to work fine even though they are now strangely almond-shaped instead of pigeon round. He bites me viciously when I put in the eye drops.

I go to the Sunflower Market and get specialty grains for him: flax seed, buckwheat groats, lentils, wheat berries, and mix them with milo and peas and corn and sunflower seeds, so Lucky eats like a king. But he bites me when I reach in to fill his tuna can with grain.

I take no offense and still try to do things to make Lucky's life a little more interesting. I used to take the cage out and set it on the coop and have a beer while Lucky had vacation outdoors under the sun. Once, however, I awoke one morning to find that I had left him outside all night on the coop, and I raced out in horror that the neighborhood cats might surely have gotten into the cage and killed him, but he was fine having spent nothing worse than a mild evening out under the stars. But I've quit putting the cage out back.

The other day, it was 112 degrees out, and it occurred to me that Lucky never got a bath, and pigeons love to bathe. I turned on the backyard hose with its nozzle in the little cement depression I had built and christened "Sierra Pond." The bloom was on the sage around the pond, and some of the purple flowers had fallen into the water. I got Lucky and set him in the pond. The water boiled beneath him, cool and bright in the burning Arizona sun. He floated, feet just touching the bottom, spinning in the water like a miniature armful of laundry. The almond eyes blinked. He spun slowly, wings extended over the shining water and the whirling purple blossoms.

EPILOGUE OF SORTS:

LUCKY DEAD February 28, 2011. God, he

was AT LEAST 24 YEARS OLD. I think twenty-five! The pigeon

check in 1985 bought his parents and he was THE FIRST to

be hatched!

Journal entry in bird database: 2/28/2011 LUCKY DIED! I went to the store and bought him some milo as I thought he might have missed it recently what with all the other seeds he was eating. When I got home he was lying on his back as dead as a doornail.

CLICK TO SEE A BIGGER, PROPORTIONAL IMAGE

Lucky Dead.JPG.jpg

dead lucky in lifelike pose.JPG.jpg

lucky perched on my hand.jpg

Lucky Resting on the Perch March 1, 2007.jpg

.jpg)

rocks crystal skull javelina villas lane schist pottery sierra pond (1).jpg

Journal entry in bird database: 2/28/2011 LUCKY DIED! I went to the store and bought him some milo as I thought he might have missed it recently what with all the other seeds he was eating. When I got home he was lying on his back as dead as a doornail.

CLICK TO SEE A BIGGER, PROPORTIONAL IMAGE

Lucky Dead.JPG.jpg

dead lucky in lifelike pose.JPG.jpg

lucky perched on my hand.jpg

Lucky Resting on the Perch March 1, 2007.jpg

.jpg)

rocks crystal skull javelina villas lane schist pottery sierra pond (1).jpg

rocks crystal skull javelina villas lane

schist pottery sierra pond (1).jpg