OH, I HAD PLANS. I SPENT THAT BIT OF JULY IN 1983 WRITING LIKE MAD. WAY LEADS ONTO WAY AND I DIDN'T CONTINUE WRITING AS MUCH. IT IS A CRYING SHAME. I AM A CRYIN' ONION!

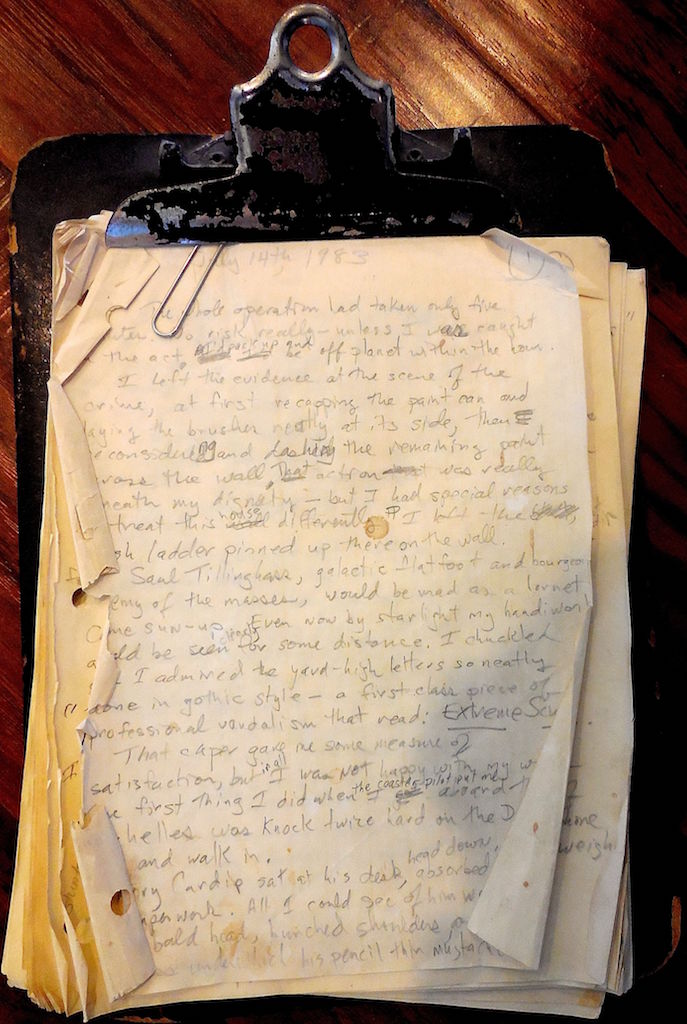

My clipboard that I had when I was ten years old and the beginnings of Planet Commandos that I wrote in 1983. See the date? July 14th.

It wasn't such a good novelette but I could tack it onto my 50,000-word PLANET BUSTERS to make it 80,000 words.

I STILL USE MY 1961 Clipboard! You see where I bent the little tabs over left and right? I stepped on it when I was ten and it poked my foot so I made it safer.

You know this is just what the clipboard

looks like today. I still use it and replace the essay. A

memory of a fracaso.

The whole operation had taken only five minutes. No risk really -- unless I was caught in the act. I'd pack up and be off planet within the hour.

I left the evidence at the scene of the crime, at first recapping the paint can and laying the brushes neatly at its side, then reconsidering and dashing the remaining paint across the wall. That action was really beneath my dignity, but I had special reasons to treat this house differently.

I left the mesh ladder pinned up there on the wall.

Saul Tillinghass, galactic flatfoot and bourgeois enemy of the masses, would be mad as a hornet come sun-up. Even now by starlight my handiwork could be seen clearly for some distance. I chuckled as I admired the yard-high letters so neatly done in freehand style-- a first-rate piece of professional vandalism that read:

Extreme Scum

That caper gave me some measure of satisfaction, but in all I was not happy with my work. The first thing I did when the shuttle pilot put me aboard the Seychelles was to knock twice hard on the director's door and walk in.

Harry Cardip sat at his desk, head down absorbed in some paperwork. All I could see of him was the top of his bald head, his hunched shoulders, and horn rimmed glasses under which his pencil thin mustache danced as he silently counted out figures. I tapped my foot, cleared my throat, and at length Cardip looked up from his papers and said: "Good work, Jenkins. The report came in just after your assignment had been completed. "Nearly flawless."

"Nearly?" I asked. I knew Cardip. "Nearly" was bad news by his standards. Cardip rose from his chair, motioned at me with one hand. "Close the door, please," he said. "Yes, nearly. You forgot the slogan we assigned you."

The door banged metallically as it shut. I turned and looked at Cardip. "Didn't forget." Wrote my own. You know, special case."

"I know how special this case was," Cardip said, flopping back into his chair with a crashing symphony of ancient springs. "Have a seat, now. I want to talk to you. Important."

"That's good," I replied, sitting. "I came to talk to you about something anyway. I hate my job. I think I quit. Lousy pay and no chance for advancement-- in fact, I've been demoted-- from revolutionary planet buster first class to some kind of raspberry expert specializing in crank telephone calls, petty vandalism, and other lightweight stuff. What gives?"

"You are valuable to us."

"And you don't want me killed?"

"Exactly."

I threw my hands up. "Oh, brother! Now I've heard it all. My last assignment was practically a suicide mission. You put me up to it too, Cardip. You've got hundreds of agents with more training than I, and they're out risking their necks all over the galaxy. Now you tell me that you can't afford to have me killed?"

"You seem awfully eager to be," observed Cardip. "Are you?"

"Not really-- in fact, the thought terrifies me-- and my poor wife would carry on so-- I think. But I don't appreciate the assignments I'm getting, and I want to know why you're giving them to me."

"I've already told you."

"Come off it!" I snapped.

Cardip merely grinned. "I mean it," he said. "You mentioned hundreds of other agents. You know that I used to have many hundreds more."

"So what?"

"So they were killed trying to complete the same assignment you had some months ago."

"And hundreds succeeded as I did. What does that prove?"

Cardip thought for a moment, pulled open his desk drawer, and extracted a sheet of paper. He looked it over quickly and handed it to me. "What does that prove?" he parroted.

The sheet was simply a list of numbers:

56,487

16,333

4055

482 etc.

"I don't even know what it is," I answered.

"Surely you do," Cardip laughed. "It's a list of mercenaries obtained in our special recruitment program. Each figure represents the number of men conscripted by each agent."

"And?" I asked irritably.

"And you top the list!" he congratulated, extending his hand.

I frowned, shook his hand across the desktop warily. "So where's my commission?"

"We don't award commissions, as you well know. Only rank. That's how you moved from private to staff sergeant in a single bound."

I snorted. "And how thrilling it was. There's just something about that uniform."

"Which you never wear," Cardip reminded.

"And look like a fed?" I sneered. I lowered my eyes. "Where's your dance set anyway, general?"

"I outrank every general in the Alliance and therefore dress as I choose," he said matter of factly. "You may, too. Actually, uniforms and even rank itself are optional. We've found that promotion in title is a good work incentive for many of our soldiers, however."

"Not for me," I said.

"But that's what makes you so special to us, my friend."

"I'm special because I brought you back more recruits than anyone else. Your affection is purely mercenary, excuse the pun."

"Perhaps," he confessed. "But you haven't examined the list closely enough."

"What's to examine? A list of numbers, from largest to smallest--"

"But the spread--" Cardip was getting impatient. "Here, here, " he muttered irritably, pulling the sheet from my hands. "Don't be so dense. Yes, 56,487 is the top of the list. The next highest is only 16,111. The difference is substantial -- no, remarkable -- especially remarkable when you see the dozens of pitifully smaller numbers below."

"I picked a good planet," I explained. "The people there are aggressive, like to fight, easy to enlist."

"Easier to anger," Cardip countered. "Yet you survived. You produced. And there's more-- yes, there's much more. From nothing you became Prime Chancellor of Marion, the most successful non-federal world the galaxy has ever produced. And the feds still can't figure out its success -- even though they conquered it."

"All my late father's doing," I reminded, becoming wary of this praise.

"But you helped-- you helped" Cardip maintained, waving me to silence. He seemed unwilling to consider any facts to contradict whatever theory he was developing. Irrational at best but flattering-- and he was right I had been elected as Prime Chancellor of Marion. I had busted the planet Tuukar and simultaneously converted over 50,000 stone-age savages to our revolutionary cause.

"You were saying?"

"Things like that simply do not take place by chance. It takes a special gift."

I swelled.

"I think I understand what that gift is now," he continued. "At least I think I do." He hesitated a moment and then said in a sober tone that nobody could ever have faked: "You were born lucky."

"Huh?"

"So I knew your worth! The only thing left to determine was loyalty and..."

"Loyalty!'

Cardip stood from his chair and pointed a finger at my nose. "Because of your promising background, I for one am sorry to find that you are sadly lacking in that aspect of service!"

"I--"

"Shut up!" Cardip exploded. "You had your orders! You were to write a scientifically-researched and specially-composed slogan. Where is it?" He rummaged through a pile of papers on his desk. "Where-- ah, here: Proletariats of the World , Unite. That slogan cost 5,000 man hours to develop. What did you write?"

"Something quite different," I admitted. "A description of the dwelling's inhabitant."

Cardip scowled, and nodded accusingly. "You mean Saul Tillinghass?"

"You know who I mean," I told him.

"Just because he bombed your planet to smithereens and exiled you, you would hold a grudge?"

"I'm like that."

"Insubordinate. Are you like that?" Cardip slammed his fist on the table. "You get orders, and you interpret them to carry out your own vendettas! I don't require blind obedience, Jenkins. But restraint and professionalism-- those I do require!"

I leaned back in my chair. "I thought it might be something like that," I said. "It really couldn't have been very many other things. Not loyalty. Professionalism-- interesting."

Cardip gaped. "What are you saying?"

I laughed in his face. "When you assigned me Saul Tillinghass's personal residence for vandalizing, did you think for one minute I wouldn't wonder why? I knew I was being tested!"

"You did? So why did you deliberately fail the test?"

"I passed with flying colors. Look!" I reached into my pocket, produced a heavy adjustable gas grenade, and tossed it in the center of Cardip's desk. It landed with a thump and rolled to one side, its yellow lettered dialsetting within Cardip's view. "I had this on me when I painted the wall."

Cardip looked down at the army green lump of iron on his desk. "Lord!" he breathed.

"I wanted to write something personal to Tillinghass of course -- not just a slogan -- but I wanted much more to flip that old fashioned dial-o-matic through his window. I also wanted to pass your test. That's why I brought the grenade in the first place. If it was restraint or professionalism you were testing, I have passed. The grenade stayed in my pocket. You can also see that I have exactly the kind of keen if twisted mind you need for some of your more challenging operations. You shouldn't be so niggling just because I got in a harmless bite against an arch enemy of mine while carrying out your orders."

"But you changed the words," Cardip argued "And as I said over 5,000 man hours -- "

"Were never ever needed for your dopey slogan." I interrupted. "I looked it up myself in the Encyclopedia Universial. Proletariats of the World, Unite-- a witless chant taken up by practitioners of an ancient and ridiculous social system called communism, which professed that people should give everything they own to the feds while the feds repay them by dictating what color socks they wear-- red ones if I understood the article.

"I passed your test, Cardip. Now, what happens after graduation?"

Cardip blanched, picked

up the gas grenade, and shook it in my face. "You should be grateful that you are part of an organization that detests slogans. We've never taught you any and haven't used any to recruit. The organization that does falls only too quickly into brainwashing and its members take on a glazed, fish-like quality. But this!" He opened his palm to let the gas grenade lie in more complete view. "This is where your professionalism flew out the window. You took a wide-range gas grenade onto a federal planet?"

"I said I did."

"Jenkins, you know why we gave you some unassuming duties down there. If you got nabbed defacing a wall, our lawyers would present it as a prank, not a crime. You'd be out of jail in two hours. Couldn't even extradite you. The grenade, however-- "

"Is a dial-o-matic, as you can see," I interjected. "Set on the harmless rotten egg mode."

"But this grenade has other settings," Cardip insisted. "From simple smoke signals to a city-destroying nerve gas."

I shook my head. "Incorrect. Look again. That small tab next to the dial."

Cardip turned the grenade over, inclined his head to peer through his bifocals. "A weld!"

"And the whole pineapple frozen as a simple stink bomb."

Cardip dropped the grenade on the desk. "Not good enough, Jenkins. The prosecution would argue that this device could be rearmed by simply breaking the weld. You'd pull fifteen years, federal pen, minimum."

I rather doubt that. Insurgent lawyers are top flight. Covalent dipole weld. Couldn't break it with a jackhammer. Stink bomb. Prank. Out of jail in two hours." I smiled at the director. "Come on, Cardip. Concede defeat. I'm better at this kind of infighting than you are. That's why you hired me -- for that and my money!-- now tell me all about the new assignment you've planned out for me."

"Assignment?"

"Please. Your character test was given for a reason. You've got something lined up for me. Something big. I can almost taste it. Don't rush. Tell me about it slowly; I want to savor each detail."

CHAPTER TWO

The man's dossier was enough to qualify him for Cardip's position, probably much more than enough. It was a thick, aluminum-bound collection of documents describing the life and works of one late George Seek, Colonel, espionage expert, and top-rated battle commando. I flipped to the last page, closed the dossier, and handed it across the desk to Cardip.

"Impressed?" Cardip asked.

"As impressed as I ever am when I read about a dead man I never heard of."

Cardip frowned, nothing more. He knew it was my nature to be difficult when information was trickled out to me in this way. "That part of the report was, of course, falsified. Seek is quite alive and at work on deeds quite in keeping with the grandness of his dossier." Without elaborating further, Cardip slid some blueprints across the desk. "Recognize these?"

I scanned the papers and said: "P-657, battlesled, world cruncher. One of those huge ships the feds have."

Correct," Cardip said. "So huge that the typical blueprint page contains a scale of miles."

"And so huge that the feds do not dare use them for the effect it would have on public opinion." I added. "Why are you showing me these things? If battleships that size were used, the federal state would have revolution on a thousand worlds that presently wave their banner. Don't tell me we're worried about them now."

"We have to be," Cardip said abruptly. "George Seek has requisitioned one!"

For a moment I just stared. Then, I couldn't help but grin. Cardip kept a deadpan face, but I didn't recognize it for what it meant. "A P-657?" I finally blurted out, wanting to laugh. I could hardly believe it. "This is great news! The federal police will be scared out of their wits, and the Special Task Force, those planet-busting hoodlums, will be outgunned by us Insurgents! I can go back to Marion! Yay!"

"Stop it!" Cardip snarled. "Do you think we would ever try to commandeer a thing like that? This was not a sanctioned operation. Colonel Seek did it all on his own."

"Even so," I replied. "You couldn't really blame him if the opportunity presented itself."

Cardip snorted. "I'll blame him all right." He muttered heatedly. "He made his own opportunity. A goddamned one-man army. Thought he knew how to run things better than his superiors. You may have wondered why I've been so touchy about subordinates doing things their way instead of the way they are told."

"I noticed," I said, for some reason feeling nervous. "But I was a step ahead of you, if you remember. No harm done. I knew your graffiti assignments were a test and not important to the cause."

"You did? Well, then you're mighty presumptuous. Since when is it your place to decide what is good for anything? You follow orders!"

"Well, yes sir!" I cried, throwing him a crisp salute. "What happened to the comradely state of semi-equality that made this underground revolution business tolerable?"

"It's right where it always has been. You obey orders because you agree to. If you deviate, it throws everything out of whack. Cooperation helps one and all." Cardip took off his glasses and looked directly at me. "Administration sticks in my craw. This Alliance may be the only example in history where the administrators weren't the moral and intellectual dregs of an organization. I made sure of that by sending anyone with administrative ambition to the front lines. That kind of artificial selection may someday help to purify the human race. In the meantime, however, I have to live with my own duties -- some of which are pretty tough -- like sending those pathetic dolts with pretensions of an administrative nature to dangerous places."

"Did they ever guess why they were winding up as cannon fodder?"

"Hell, I told them up front!"

"And they went along with it?"

Cardip stared at me. "Are you kidding? They quit to the last man. And good riddance!"

"I didn't think it was like you to have anybody eliminated. Not so cold-bloodedly, at any rate."

"I may yet," said Cardip. "At least when I think about people like Seek."

"I'll bet your wrath will be tempered somewhat by the sight of that battle wagon. It's one heck of a bargaining chip."

Cardip put his glasses back on, took a deep breath, and let the air escape. He shook his head as he observed me with what seemed to be pity. "Jenkins Basil Lai," he intoned. "You may be a very smooth-tongued and capable if lucky man, but you have no grasp of interplanetary politics."

"I never professed to be an administrator," I countered, looking directly at him.

"Just a huckster?"

"Perhaps."

Again a sigh. "A battlesled is a problem, Jenkins-- not an asset. It represents a responsibility no one in his right mind wants or needs."

"But--"

"'But' nothing! If the feds are afraid to use one of those monsters, then what the hell am I going to do with one? Picture yourself as a discontented yet placated Federal Worlder. The government makes life dull, but if you tow the line, you and the members of your family are left alone. You can even advance to a certain stage before your path to a higher-paying job is blocked by federal nepotism. You probably don't approve of the fact that the government is stomping the devil out of defenseless thirdworlders-- but those thirdworlders don't join the glorious federation, so that's the way they want it, right?"

"Wrong!"

"I know it's wrong, and you know it's wrong-- but what does your average federal world inhabitant know?"

"Not much."

"He knows nothing!" Cardip affirmed with conviction. "-- and he's the one we'd like to convince of our sincerity and decency. For all the information he gets, his government hasn't done anything drastic without the most severe provocation. Nobody sane loves those world crunchers, yet it's an historical fact that the feds haven't so much as killed a mosquito with one in over four-hundred years. The Federation's half-loyal subjects have noted that fact. What condition do you think their nerves will be in when they learn that some mad revolutionary group has stolen the means to lay planets to waste at will?"

"Frazzled, I should think."

"And they'll demand that the government do anything and everything possible to reestablish the status quo-- including..."

Cardip broke off and looked at me with a pained expression.

"Including what?" I asked irritably. "Don't tell me you are straying onto a classified topic."

"No," he said. "I just hate talking about it-- or even thinking about it. Including the use of L-80 proximity bombs directed at the Seychelles herself ."

This caught me by surprise. "The Seychelles?" I sputtered. "They know about us?"

"Of course," Cardip said with an indifferent cough. "They always have, you know. We've avoided trouble by playing hide and seek. Our crew simply punches the ship into ultra drive and makes random turns on our way to any particular destination. The feds can't catch us that way, but they often can guess our general location."

"But they can't just detonate L-80 proximity bombs. I've read about them. Not bombs, really; a field, rather, which when activated, appears anywhere in the galaxy, instantly destroying all matter within one to two parsecs. And the aim is haywire. To get us, they'd have to risk punching holes through shipping lanes and knocking out worlds and worldlets all over the galaxy."

Cardip shrugged and smiled wryly. "Drastic circumstances require drastic measures," he said simply. "Which would you rather have: a calculated risk or a madman doing the unexpected? I'll answer for you: you'd pick the known evil over the unknown, and you'd be right. Just as the feds would be right in destroying us."

"Destroy us?" I gasped. Yet I knew exactly what Harry Cardip meant. One does much to trust a government duly elected. A dictatorship? Never. Revolutionaries? They could be trusted in troubled times, reluctantly. But who could be trusted with such power? Nobody. That was the problem since the first atom bomb.

Cardip seemed to have read my thoughts. "The feds should have destroyed the P-657's centuries ago. They preferred instead to parade those hideous engines of destruction around for political purposes, underscoring the glorious achievements of the Federation. I honestly believe that in recent times they have all but forgotten that those lethal machines are weapons. The ships became more like symbols of technological accomplishment. Now I believe the feds have finally seen them for what they are and regret very much that they exist-- as I do."

"But this is our chance!" I shouted. "We can at least destroy one of them. Pack it full of explosives. You can publicize the event. The galaxy made safer-- and all in the name of the Insurgents' Alliance of Sovereign Worlds!"

"I can't."

"What?" I thought he must not have been listening. "Why the hell not?"

"Because George Seek will not surrender the ship. He's giving the feds all kinds of ultimatums and threatening to blow up half the galaxy-- all, as you say, in our name."

CHAPTER THREE

It was six days later, and I had the beginnings of a plan worked out in my head. I had succeeded rather spectacularly before by relying on a certain caliber of man to aid me, and what had worked then just might do so again. Cardip had pulled out all stops, and each agent was expected to drop everything and go after Colonel Seek with as he put it, "Whatever resources are possessed." Well, it just so happened that there were some resources I needed. The Director was not enthusiastic about my plan, however.

"Heliox?" Cardip exclaimed. "Why in the hell would you want to go back there?"

"I have my own good reasons," I told him.

"Reasons? What reasons?" he railed. "Are you crazy? George Seek is not on Heliox. How do you expect to stop him by going where he isn't? Go where he is for God's sake!"

"Where is he?" I challenged.

"He's-- well, out there somewhere else. Go get him!"

I winked and stared down at him slouched in his chair. "Mind if I sit, Chief?"

"Since when did you ever ask permission to do anything you felt like?"

"Thank you." I sat, crossed my legs, and lighted a cigarette. Cardip reached under his desk and flipped a switch. There was a whirling sound just above my head. I exhaled and watched the cone-shaped cloud disintegrate and vanish almost instantly. The smoke emanating from the tip of the cigarette was a perfectly vertical thread, web-like and rising. Even some of my hair was standing up. Evidently, Cardip had installed some new equipment after my last visit. But I pretended not to notice. "I intend to 'get him' as you say, but only in the way that I think is best. It's my neck after all."

"I thought you had given up that filthy habit." Cardip complained, wrinkling his nose in my direction with displeasure.

"I did. I started again. The custom is still quite in vogue on Heliox, you know."

"Which shows what an intellectual hinterland the place is. But that would appeal to you. Now, answer my question: "Why are you going there?"

"I like that," I said. "'Why are you?'" not 'Why do you want to?' It shows that you have resigned yourself to the fact of my going and-- "

"Answer my question!" Cardip stormed. His face was red and laced with tiny blue blood veins which contrasted nicely with the large ones on either side of his neck. Those stood out prominently. I thought of the vessels unseen within his cranium and decided to cooperate a bit. I preferred him flustered, not dead.

"I need men for the job, Harry," I explained simply.

The Director's face cleared somewhat, and he swallowed almost gratefully before he spoke. "Men? I told you I would supply you with men. I'll give you a veritable army of them. When do you want them? Just say when, and you'll have them. Then, you will go out after Colonel Seek and never come back to bother me!"

"I want them now, if you please," I answered. "And I have a list of them right here for your convenience." I handed the list to him, and he tilted his head, peered through his bifocals, and immediately gave it back.

"You can't have those guys, and you know it," he said.

"Why not? I worked with them before and we practically conquered the planet Tuukar together."

"They are under different leadership now." Cardip told me. "I believe you can guess whose."

"Dave McKellen's, right?"

"Correct," he affirmed. "And you ought to agree that it's only fair since he recruited them himself."

"But who trained them---"

"He did."

"Yeah, but who gave them the real field experience that they needed? Answer me that."

Cardip sighed. "I'll admit that you did. Now it's your turn to admit that those men were only under your command as a loaner. McKellen recruited every one of them."

I mulled this over for a moment, then had inspiration. "Every one?" I cried. "Not quite, my friend. That list was alphabetical. Whose name appeared last?"

A cough escaped Cardip. It had nothing to do with my cigarette, which I had butted out on the arm of my chair. I lighted another one. "You can't mean Zallaham?" he sputtered. "The warlord of Huria himself?" The Director snorted derisively.

"What's so funny?" I protested. "He's mine. I found him. I got him. I brought him to you!"

Cardip grinned. "Zallaham yours ?" he asked sarcastically.

"In a word, yes. Mine!"

"You had better hope he doesn't hear you saying that, you know," Cardip warned nervously. He seemed to be fighting back the impulse to look over his shoulder. "For Pete's sake, even McKellen has to keep up his guard with that powerhouse around."

"So you won't give him back to me?" I fumed. "I risk my neck to bring you a one-in-a-million stone-age military genius and muscleman. And you think he's just too plain good for me and give him to somebody else."

"You know he's too good for you, Jenkins," said Cardip, mincing no words. "But I didn't say I wouldn't give him back to you. He's yours. Go tell him."

I stood up and leaned over his desk, pushing my face close to his. "Listen, you. You're not going to wiggle away that easily. You assigned Zallaham to McKellen, and you'll personally assign him back to me or I'll know the reason why."

Cardip was leaning way back in his chair now, anxious to be away from my face and cigarette halitosis. "Agreed," he said quickly. "Just sit the hell back down."

I sat smiling. "That's nice. That's very nice. It's also too easy. What's the catch?"

Cardip shrugged. "None," he replied. "You have no right to ask for the others on the list, of course. They are simply out of the question. To Zallaham, however, I agree you have some tenuous claim."

"So you'll order him to report back to me?"

"I'll ask him," said Cardip. "One does not give orders to the likes of him, as you must already know."

"Good enough." I got up and shook Cardip's hand. "I'll collect him when I get back."

"From Heliox, I presume?"

"Of course. I know that the soldiers you would offer me are nothing more than company climbers in permanent high gear. They're ambitious and will resent any directions I give them."

"Can't stand the competition, eh?"

"I can stand it all right, thank you." I told him. "But I hardly think it's useful. An operation needs only one operator to run at all. And with your guys, let's face it: we'd practically be peers."

"I don't know whether they would appreciate being characterized as such," Cardip parried. "But if that's your only complaint, I think I can offer a solution to your dilemma. There is still a virtual multitude of Zallaham's Tuukarian infantrymen whom I would be more than happy to assign to you. I can promise you that they will not be overly ambitious."

"Nor overly bright either." I countered. "I, of all people, don't think much of those who degrade the natives of third world planets, but I think it's fair to note that McKellen's boys from Heliox made chumps out of the lot of them. Took them for what little wealth they possessed using the most transparent bait and switch schemes imaginable. I think I'll pass."

"So it's off to Heliox, then?"

"That's right. I don't need competitive intellectual equals, and I don't need unambitious morons. I'll tell you what I need. I need savvy bastards who were just plain born to lose. Men with street brains but no higher intelligence -- and no pretentions. The classical criminal type. And, by God, Heliox is one place I can find them!"

***

I left Cardip to his devices and walked through the open galleries of the Seychelles. It was a way I had of unwinding. There was something in the raw utilitarian rusticity of the ship that relaxed me. Once, it had been perhaps the greatest luxury liner ever built. It had grown older but never obsolete. Passengers clamored to get tickets aboard. But the Federation overplayed its hand trying to dip into the coffers, the result being an uprising that played a part in Insurgent history. Our organization was on hand to aid the aggrieved crew, and the organizers of the rebellion were more than happy to fall in with our cause. For one thing, the Federation's penalty for mutiny was harsh indeed and the rebels needed our sanctuary. Now, the fabulous Seychelles had been requisitioned and souped up. It had also been stripped down to its bare rivets and fleeced of its finery. The ship was simply a shell of what it had once been.

I didn't agonize over that as some people did. Cardip had once confided that he had hidden the great oak banisters, the gleaming chandeliers, and all the rest of what was truly the Seychelles in some unheard-of place. When the revolution was over, he planned to put a great team of craftsmen and artisans to work restoring the ship. After that would follow one whale of a celebration on board.

When I got back to my quarters, Lourdes was not in. I noticed that she had put up some extra pictures: seascapes, virgin dunes, and an exquisite panorama of Marion's Norsano Desert. Perhaps that was her way of dealing with her lost home, but I wished she hadn't done that. It just made me homesick for my beach retreat on the Paradise Coast.

"Like them, Jenkins?" It was Lourdes. She had come in so quietly that I hadn't even heard her.

"Lovely, indeed!" I had to humor her. "Soon we'll be back there soaking up that sun, not a care in the world, an honest day's work only a hateful memory."

Lourdes stepped over and straightened a seascape. "Have you been following the news about Colonel Seek?" she asked. "The Federation Broadcasting Network is making real hay of the whole debacle. It's a smart move on their part. They know that that man could ruin us in about ten seconds flat."

"He could," I agreed. "But don't call him Colonel. I think a more proper title would be "lunatic." At any rate, I plan to catch him, drag him back here, and strip off his medals along with as much of his hide as happens to come off with them."

"Don't work yourself up," Lourdes warned, frowning. "You know how you get. All puffed up and not a wink of sleep for a week."

"I always

get that way before a major assignment." I told her.

Lourdes scowled. "Always?" she asked. "You've had exactly one to date, and it was I who lost sleep in the end. I was never so surprised in my life when you came back alive from that awful planet Tuukar."

"It was awful, I'll have you know. And to tell you the truth, I was a bit surprised to get away with some of the stunts I pulled myself. I just hope you weren't disappointed."

"I wasn't. Just surprised. Grateful too. The Federation in taking over Marion made us involuntary citizens, and as such we are subject to its antiquated laws -- whenever we decide to start obeying them, that is. The Federation is not a community property state, and in addition it exacts a hefty inheritance-type tax on the property of a deceased spouse. A widow today I would not like to be."

"I knew it was only my half of the estate that you cared about..."

Lourdes looked at me sternly. "Tell me the truth. You were joking just now when you said you were going after Colonel Seek, weren't you?"

For a moment I thought of lying, but at the last second I thought better of it. Lying to Lourdes was madness, suicide. She always found out and then there was literal hell to pay. I plopped down on the bed. I had to admit it; there was no other way.

Lourdes didn't take the truth well. I almost wished I had lied after all -- or maybe just fibbed a little. She was adamant: I would leave her a widow, I would ruin her life, I would do this and that..... "But Lourdes," I tried to explain. "Everyone who is anyone is going out to have a crack at Seek. We have to. If that psychopath pushes the wrong button, it's the end of our revolution. We would just have to pack it in and wait another four-hundred years for our time to get ripe again."

"And what about me, then?" Lourdes asked. "I just sit in our quarters aboard ship and wait and worry? You say everyone's going. Well, fine. I've had every bit as much training as you, haven't I?"

"Well, yes." I snorted. "More so in fact."

"Well?"

"You want to come with me?" I asked in surprise.

"It's better than waiting around here and trying to manage your harebrained business enterprises, ninety percent of which fail miserably."

"Ninety percent of everything does," I reminded her. "It's the ten percent that's the charm," I said. "But I didn't know you wanted to go."

"What else is there for me to do?" she asked. "I hated every minute of waiting the last time you were out. And if I have to stay aboard this glorified flying trash can this time, I'll go absolutely crazy. What's more, I never liked that bible-thumping George Seek anyway. It'd be a pleasure to haul him back kicking and screaming. I'll hold him and you can kick. We'll leave the screaming to him."

"You know the rat?"

"Not personally. However, when you were out tromping across the frozen plains of Tuukar with your felons at large and your legions of bad-tempered Eskimos, I attended a few presentations aboard ship. One was given by Seek. It was the last I attended. Couldn't stomach the topic."

"What was it? Military strategy? Weapons deployment?"

"It started out dealing with similar themes, but soon regressed into something less attractive. Colonel Seek, it seems, believes in a supreme being."

"No!"

"I'm afraid so, Jenkins. He went on and on about woman evolving from the rib of a man and a galaxy-wide intrusion of hydrogen and oxygen in a two-to-one solution that killed all life in its path. It was real scary and I left."

I shook my head. "Well, if that don't beat all."

"Now," said Lourdes. "Am I going with you, or do I go after the bum myself?"

I protested, of course. I said everything that a concerned husband would say. She would get hurt. Heliox, combat, deep space-- bad for woman! But my heart wasn't really in it. The fact was, I wanted her to go. I hated being without her to the point that it had almost jeopardized my last mission. And it wasn't as though she couldn't take care of herself. For her size she was at least as tough as any man. To tell the truth, I felt pretty sure she could beat me up if she really put her mind to it.

I didn't express to her directly how I felt, of course. When I left her, I made it clear in no uncertain terms that a mere woman would never accompany me on an assignment, but Lourdes knew that I did not mean it. The belief in male superiority was an aberration of the stone-age. And what kind of woman would marry a man who believed in such a thing? (Woman evolving from a rib indeed!) In reality, with her willing to go, I had an entirely new outlook on the undertaking.

It didn't take long to find out I had made the right decision. I ran into Cardip about an hour later. "Good news," he said. "I talked to both Zallaham and Dave McKellen. Zallaham has been reassigned to you ."

"Good. You work fast Chief." I responded.

Cardip started to walk away, then did a little double take and spun on his heel. "Er, there's just one problem." He said offhandedly.

"What's that?

"Zallaham refuses to have anything to do with you, and McKellen says he's going to knock you around some the next time he sees you."

CHAPTER FOUR

I heard the commotion inside the room even before I opened the door. I took a deep breath, turned the knob, and strolled in casually. The noise did not abate for even a moment, and that did not bode well for me. My appearance there was unexpected and should have produced a communal gasp and a scrambling rush of activity to conceal the mischief followed by sheepish grins and a chorus of ingratiating if affected salutations.

Instead, the boys from Heliox ignored me altogether. They shouted the foulest obscenities at one another and continued to make boisterous side bets on the outcome of something truly disgusting.

In the center of the Formica table was a foot-long plank upon which sat a floppy-eared creature known as a Grangorian rabbit. Biffer, a thin whiplash of a chiseler, was directing some sort of ray at the animal's head while his companions roared with excitement, sheaves of the inflated paper currency of Heliox clutched tightly in their hands. There was a long trough of liquid in front of the rabbit and just beyond it was a spindle upon which was impaled a rather moldy potato. An uncapped jug beneath the table read: 25M H2S04.

It didn't take me long to figure out the game. The trough, of course, contained sulfuric acid, and the ray that Biffer was dutifully administering to the creature's cranium was undoubtedly designed to stimulate the hunger center of the lagomorph's brain. When the ray had worked up a colossal appetite within the rabbit, the luckless animal would leap with uncharacteristic voracity toward the potato. And, of course, land directly in the acid. A stopwatch would click and those having correctly predicted the time of the event would divide the pot.

Of course, they could have played without the acid.

There was a sudden splash followed by an enormous mishmash of outcries. The throaty groans and curses of those who had lost were all but drowned out by the ear-splitting whoops of pleasure from the winners.

Biffer was fast at work at the trough with a smoking fork with which he first skimmed the fur off the top of the acid, then fished out the bleached and disintegrating skeleton.

Things were plainly getting out of hand. I had simply started out too loose with these boys. Now came the unpleasant business of tightening things up. "Who's the big winner here today?" I said cheerfully, putting on a greasy, almost lewd smile that this crowd understood only too well -- or thought they did. Kroin, the biggest and ugliest of the bunch stepped forward, eager to claim the honor. Perfect. I had been hoping it would be him.

"Me," he said stupidly, and motioned to a cage against the wall. "Win more later, too. Got ten rabbits left."

"One of them's getting away," I told him and when he looked to see, I punched him directly in the teeth.

Kroin screamed gagging in pain and staggered about the room in circles. The rest of the company gaped in surprise, then grinned in anticipation as Kroin regained his senses and turned his attention from his splintered teeth to me. "Ahrgg!" he screeched and bounded toward me.

I stood firm, feet planted well apart. It didn't take a genius to foresee his intentions. Kroin halted about two paces from me and kicked with all the savage intensity he possessed in his rage. The man's heavy number-twelve boot caught me directly in the groin, the force of it practically lifting me from the ground. To the surprise of the onlookers, however, it was Kroin, not I, who fell squalling in agony.

I knew the kind of ruffian I would be dealing with here on Heliox and had made preparations in the form of a stainless steel scrotal cup. I also took my precautions a bit beyond the ordinary by taking this protective garment to the Seychelles metal shop where I welded on a two-inch dock spike where it would do the most good. Now the cup not only protected the wearer, but also quite effectively punished the offender. I was surprised at how well it worked.

Kroin lay groaning in pain, dividing his attentions between the ruins of his teeth and his punctured metatarsus. In the top center of his right boot was a quarter-inch hole from which oozed a thin trickle of blood. Around the fallen giant lay a scattering of red-backed federal guilders. I scooped these up with a sudden, aggressive motion and Kroin cringed quickly in alarm. I peeled off a couple of bills and tossed them at him. "Here's a hundred bucks," I said. "I recommend J. Patrick Gambles. He's a dentist." But I hadn't finished. I smiled sarcastically at the others, then began to kick Kroin where he lay. He yelped in pain and scrambled frantically around the room. I pursued him doggedly until he was finally able to escape through an open doorway.

From the hallway echoed the desperate and uneven clomping sound of his new and unaccustomed stumbling gait. "He'll be beating time with that good left pin for at least a month," I snorted with just the correct mixture of amusement and contempt. "Anyone else here bet I can't do the same to them?" I made a fast move in their direction and the lot of them shrank backward, mouths forming little O's, wrists clutched to their breasts. "Good. I'll be back in an hour and when I am, this room had better be immaculate. I want this whole place licked clean."

***

I could not help but laugh when I related what happened to Lourdes. She didn't find my description of the day's events particularly humorous. I had to explain that I had merely inflicted pain and had done so for a very good reason. True, Kroin's smile had suffered somewhat, but he never smiled much anyway. And modern dentistry could undo what I had done, though why anyone would want to restore any part of Kroin's ape-like visage would be unfathomable. Frankly, I felt my pummeling had improved his appearance to a degree, although it would certainly have been Kroin's right to disagree with me on that point. However, far from unwarranted and inexcusable, my preemptive assault was a necessary, sane, and in some ways humane action. Punishment under the rules of Heliox's roughnecks was most often far worse. In perspective, Kroin had gotten off lightly. And I had no choice in the matter anyway. I knew the men I was dealing with, and I knew a fate far worse than Kroin's was awaiting me if I failed to gain their respect.

Lourdes seemed to understand me better when I told her what happened to the Grangorian rabbit. She was hardly a bleeding heart, but like anyone else knew there was something fundamentally wrong with people who torture animals or other people to death for money. She tried to lump me in with their ilk, but I hastily pointed out that I hadn't actually killed Kroin -- just badly wounded him, and no tender had changed hands.

Now she was interested in the immediate future. The house I had rented on Heliox was a dilapidated two-story vermin run, and my wife seemed eager to move out of it. I rather liked it because I had reserved the entire second floor for Lourdes and me. We'd fixed it up a bit and it was livable. Downstairs, the ruffians had been allowed to swagger however they liked, which had only spoiled them. The recent public thrashing of Kroin had ended all that. And there were other changes soon to come. Yet Lourdes was impatient. "Look, Jenkins," she complained as we sat at our upstairs dinner table. We had finished a nice cut of steak and were enjoying a cup or two of coffee. "You did all right I suppose in getting Kale Soldat, your old buddy from your Tuukar days, to give you a list of ex-felons and two-time losers whom you could contact on Heliox. You've collected about thirty of the bums here simply by offering them the unfamiliar luxury of a roof over their worthless heads. Those few who are of more account have been offered the most ludicrous and unlikely rewards for throwing in with you. In the meantime, George Seek has disappeared from sight and may decide at any moment to demolish the greater part of the galaxy. If I may be so bold; just what in the hell do you think you're doing?"

"I have an answer to that question," I said. "And part of it has to do with those materials I asked you to review for me today."

"I reviewed them," she said. "But I don't know why. Only one item seemed to have any bearing on Seek and his whereabouts." She set her coffee mug down, got up, and took some papers from the nearby desk. I noticed the compu##ter on-off light still glowing redly. So did Lourdes. She snapped it off and sat back down at the table and perused the papers. "These are the print-outs from the data you gave me. That little Marion-made computer works like a charm, although I still can't understand how you got it through spaceport customs. Heliox is famed for its hard line on imported technology."

Not all of my talents were lost on my wife, I could see. "Heliox is a federal planet," I explained. "Its limited autonomy is assured provided that the populace behaves. If they don't, out goes good ole King Caleb, usurped by a genuine Federation lackey. Caleb wouldn't like that. So he's as careful as he is brutal. Computers can make the work of rebellion easier, and like all such tools, they are strictly regulated here. But the more rules imposed, the more people become set on circumventing them. Most of those people in the end are officials, and officials of corrupt governments everywhere practice a common trade: la mordida."

"La what?"

"La mordida, the bribe," I replied. "The one and only cooperative interchange between official and common citizen on such worlds. Both are victims of the government, and in a mutually helpful spirit both benefit by thwarting the desires of the greater enemy, the despot himself-- in this case King Caleb."

"Okay," Lourdes sighed. "So you greased a palm or two to get the computer in, and you are grateful. But you know very well that the official is usually committing extortion when he demands a

bribe -- so enough for your cooperative spirit nonsense. What language is "mordida?"

"Spanglo," I said, as though the answer couldn't have been more obvious. "I'm surprised you don't know it, Lulu Crane."

Lourdes looked at me. " Please?"

"It's your name; it's Spanglo! Lourdes Garza means Lulu Crane."

"That's nice. Is there some reason why I should care?"

"Because if my hunch is right, where we're going, your name will fit right in. Mine won't, so I'll have to change it. How does Jaime Loro sound?"

"Asinine," she said bluntly. "I don't think I'm going to like that language. But don't tell me; I can see that you think that our friend Colonel Seek is at this very moment lurking on some planet where Spanglo is the official tongue."

"I do, indeed."

"And the reason for your belief has to do with the information that I processed and analyzed for you?"

"Yes," I replied. "I need a second opinion to be sure that the theory I have formulated merits investigation. You haven't told me what you discovered yet, so I'd like your analysis. You said that there was one item that could pertain to his location."

"There was one -- and only one; I didn't know what the rest of the data were all about," Lourdes said. "Anyway, the battleship that Seek filched from the Federation was one that hadn't been fueled in one-hundred years or so. Both its propulsion and armament systems operate at only thirty percent power."

"That information, of course, was not expressly stated in the six million pages of public relations information included in the data I gave you."

"No, but it is a fact as deduced from the discrimination software in the Marion computer."

"The Federation did not try very hard to conceal that particular datum, did it?" I noted.

"Why should they have? What was someone supposed to do with that kind of information -- use it to steal a world cruncher?"

"Seek may have," I remarked.

"Yes," said Lourdes. "But you wanted to know how this could relate to his whereabouts. Frankly, the link is not particularly tantalizing. It is only this: if Seek were so inclined, he might take steps to acquire fuel to develop full power for his engines and arms. He'd have a problem, of course; those super-sized fighters are ancient things and some of their technology was hopelessly antiquated even at the time they were built."

"They're powered with simple 20th century atomics." I said.

Lourdes nodded. "Yes, so gassing up a ship like that is no simple matter; the Federation itself waits fifty to one-hundred years to bother with it. And Seek knows full well that the feds will be keeping a wary eye on their fuel dumps. To conclude, the analysis tells us that he might possibly be mining fissionable material. Somewhere."

"That's it," I exclaimed. I poured us each an extra cup of coffee. "That's what he is doing. He has to. He must mine."

Lourdes sipped her coffee and frowned. "Has to? Must?" She questioned. "That is not my conclusion. My conclusion is that he will not mine. Why should he? He can run that P-657 for another hundred years and demolish a dozen planets a day every day. That should satisfy him."

"It won't," I stated flatly. "That is the mistake that the Federation and the Alliance are both making. They assume that he is moderately content with something less than a full-blown world cruncher. I contend that he is not."

Lourdes set down her mug. "Content he may have to be. Mining the fuel would be a tremendously complicated and unpleasant business. It would probably also compromise his security to wait around instead of striking while the advantage was his. And powering up a ship like that from raw materials would also take forever. Jenkins, he just won't do it."

"Six months," I disagreed. "With machinery in place now, it could take even less. There is a library aboard that ship. Seek won't be bored. He's the type that could happily spend that time just rubbing his hands together and laughing maniacally."

"It's a longshot..."

"No, it's not. And the argument is simpler than that," I said. "Either he will mine that fuel or he won't; those are the only two possibilities."

"And I say he won't." Lourdes said stubbornly.

"Fine," I scoffed. "And by limiting your thinking in that way, you, like the Federation and the Alliance, stop dead in your tracks without a clue as to where the criminal might be. If, on the other hand, you had embarked on a different train of thought -- one based upon the opposite assumption -- you would inevitably have been led to the same corpus of facts and circumstantial evidence that has revealed to me his intentions as well as his location."

"What information could possibly give you all that?" Lourdes asked disbelievingly.

I only grinned and stirred my coffee sagely. "I can sum up that body of evidence with two words: Armageddon and carnotite." She started to protest, but I raised my hand and waved her to silence. "Yes, I know you have never heard of the former. It's an obscure reference. Armageddon refers to the upheaval that Colonel Seek's benevolent supreme being has planned for everyone who isn't exactly as mentally unhinged as he. Fire, brimstone, gnashing of teeth, bloody horse flesh on the highways, that sort of thing. Don't laugh, now. This doctrine has actually been written down, and Seek believes it. I checked. Carnotite is...."

"A rather complex yellow mineral which contains uranium," Lourdes said quickly. "I could recognize it in the field when I was ten, so don't assume it's also something new to me. I thought you gave me the job of analyzing data on that and other minerals because you were a lousy chemist -- which you are. Now, I see that you are just double-checking your own conclusions again."

"Nothing wrong with being thorough, is there?" I asked.

"No, but what you gave me on carnotite makes no sense," she answered. "I can see that you are developing some theory that Seek will try to mine fuel from carnotite."

"He will. I'm almost sure of that."

"But that's ridiculous," she objected. "Carnotite is comparatively poor for such a purpose. There are much better and more plentiful ores for the uranium he needs."

"I had already surmised that when I gave you the data," I responded. "That's why I asked you to establish the location of a place where large deposits of carnotite are present in conjunction with rich natural reserves of more usable uranium ore."

"I did so. There are three worlds that stand out above thousands of others."

"Which of the three has the most carnotite?"

"Ancho."

"I knew it!" I shouted. "That's where we're going, Lulu."

I then told Lourdes the facts uncovered in an investigation that I had conducted even before leaving the Seychelles for Heliox. My study concerned the character of the man, George Seek. I went over his academic transcripts and found a Ph.D.. in physics from Syrius Tech, no slouch degree that. But his post doctorate publication record was spotty. Just some uninspiring papers in the journals on carnotite and its affinity to other minerals on various worlds -- actually a subject well outside his field. On a hunch, I did a computer scan of unrelated publications. I was checking to see whether he had strayed even farther afield. I had guessed right, and what I found was chilling. His name appeared predominantly in the most obscure sectarian publications: magazines with titles like Sweltering Disciple, Holy Infarction, and Blessed Gazette. Again, the subject was carnotite, but his treatment of the topic had taken a bizarre theological turn, relating the "music of the spheres" and a supreme being with the chemical properties of carnotite and its associated minerals.

That may sound silly, but Seek was deadly serious. He did meticulous studies of the decay of radioactive isotopes in Carnotite, attempting to prove that the fossils so often associated with the mineral were recent relics of an intragalactic deluge referred to somewhere in written dogma. It was his opinion that carnotite had been placed in the universe as evidence for the great design of the supreme being.

His presentation was always kind of oblique and fuzzy and left out the most blatantly obvious and pertinent facts that would destroy his arguments in an instant. But it was fascinating reading because it went beyond most of the other articles in these publications.

The other magazine pieces relied heavily on the same tactics of omission and slight of hand. But they were composed by mental midgets, who were much too demented to see their own self deception even as they passed their delusions on to their readers. These contributors reveled in using block-long words that they didn't really understand, and the subscribers, most of whom would have to consult a dictionary to spell the word, "cat", were, of course, none the wiser.

Seek was much different. His constructs and dichotomies seemed directed straight from the subconscious. His typical reader was simply an intellectual chucklehead or suffering from moderate to rather severe mental illness. Seek, however, was truly mad.

This had dawned on me as I read in the Seychelles library some weeks earlier. And I almost recoiled at the revelation when it struck because I knew that George Seek was capable of anything, and that his vision of Armageddon could very well be a prophesy which he intended to fulfill himself.

It was obvious that for a proper doomsday he would feel absolutely compelled to get the ship up to full power. He would mine that fuel, all right. And he would use as much carnotite as he possibly could.

I could read him like a book.

CHAPTER FIVE

Both Lourdes and I recognized the necessity of ridding ourselves of better than half the roughnecks I had gathered together. Many of them fell short in the intelligence category, while others simply could not be trusted under any circumstances. We only needed about eight of them, but we figured with the group we had, we would have to take on ten. If we took any fewer, long standing buddies and cronies would be parted, and these partnerships were important in maintaining morale.

As for the purpose of the trip, I at first considered concocting some story of gold and looting on Ancho. That would keep the boys interested and loyal enough. But it would also involve a lot of interruptions and lawbreaking along the way, neither of which was particularly desirable. In addition, sneaking up on Seek on some third world planet without his getting suspicious would be hard enough without the constant pressure of maintaining the trappings of a farcical mission. Instead, I decided to pay them outright, with added bonuses in cash for meritorious service as well as promised shares of whatever treasure or booty was to be divvied out.

No, I wouldn't stop talking about looting or racketeering around this group. They were pirates and would only be happy if pirating were a part of the activities to come. But if they asked what I was doing on Ancho, they would be told to mind their own business. In exchange for money, I felt sure they would lose their curiosity.

That I was paying cash would not sour them on the project either. And it was fine with me. Cardip had opened the Seychelles vaults and every penny requested was being granted for the purpose of apprehending Colonel Seek. I had enough money to finance just about anything and didn't feel guilty about it either; after all, a tremendous amount of that wealth was actually mine.

Lourdes reviewed my analysis of Seek's wild-eyed publication record and agreed with me that Ancho was the place to look for him. She had another concern, however.

We were in our upstairs apartment packing, which was not a difficult job. The computer would simply be abandoned and the kind of clothes we would need for Ancho would have to be bought elsewhere. Most of what I was putting in my suitcase was money. "Jenkins," Lourdes said seriously. "I assume you have notified the Alliance of this Ancho business. After thinking about it, I have to admit that it is not as completely crazy a notion as I first thought."

"I've had that feeling all along," I told her. "For that reason, I went directly to Cardip himself before we even came here and showed him everything I had on Seek."

"And?"

"He didn't agree with me," I said. "It's that simple."

"But surely this is better than the hit-and-miss strategy the Alliance is pursuing now. We at least have some reasons for believing Seek could be on Ancho. What is the Alliance's game plan? All I see now is an organization with an army of mavericks chasing down leads with no direction at all."

"I'm not sure," I replied. "Cardip wouldn't tell me. There is an Alliance strategy, however; I know that for a fact. Cardip didn't want me in on it. He let me know in no uncertain terms that I was to have nothing to do with it."

Lourdes let out a sigh. "The evidence we have is not strong," she said after a pause. "But it is interesting. It's smart to look into it. And Cardip is too smart to ignore it."

"Oh, but he's not ignoring it," I stated, trying to clarify. "He's got me -- and now you -- on the project. Get this: we're to report in by O-X radio, apparently the only restriction on us. I've got an O-X packed in some of the luggage we haven't bothered to open."

"Cardip offered just the radio and no personnel?"

"I tried to get Alliance back-up logistical support, but he scoffed. Others high up didn't think much of my ideas either, though they were less derisive."

"So for manpower we've got nothing but your gorillas."

"Yeah," I said. "These guys are perfect. They know how to run from a fight without making it look like running. Yet, they are also quite willing and able to slug it out if they have to. Their most important asset, however, is their look."

"What is that supposed to mean?"

"Simply that if and when we run into the Ancho version of the Heliox hooligan, the two groups will instantly recognize their off-world counterparts. Instead of an outright attack, there will be a bit of he-buck strutting and positioning and raised hair-- it's the same on every world. Usually harmless enough. Some headbutting at the least and maybe a little knife play, but the heat will be off you and me whatever happens. That's important; Ancho is a rough world in many places, and I intend to do some traveling right out in the open."

"That's good as far as it goes," said Lourdes. "But I wish we had some Alliance support. I still can't understand the administration's inability to anticipate Seek. Can't they see what that schiz is likely to do?"

"Perhaps they would be able to if not for the religious element," I offered. "They come from modern worlds where one does not see much of the old-style fundamentalist zeal."

"That could explain it," Lourdes admitted. "Now, however, you and I are stuck with the job of going to Ancho. We'd better keep our fingers crossed."

"That Seek is or is not there?" I asked.

"I haven't decided that," she answered.

***

Dumping the twenty-odd ruffians whom I didn't need was child's play. I began by telling them that I intended to ditch the others. Then, I pulled a switcheroo. I'll never forget their faces as they watched the shuttle bus to the starport rumble by without them. They stood stupidly at the curbside, bags in hand, gaping at the twelve grinning faces pressed against the windows of the bus. I tossed them the tiniest wave just before the shuttle rounded the corner out of sight.

Among the ten from Heliox were: Biffer, the wiry thin huckster with a face so evil that his own mother must have feared him; Marlow, a transplanted Grangorian who was on Heliox simply to escape his creditors; Nils, a tall blondish chap whose penchant for liquor made him fairly unusable for stretches of time; Hardiman, good with engines and better with his fists -- a temper to match, too; and a variety of other more featureless alley cats among whom was the giant Kroin, who bore me no malice for the thrashing I had given him; he was more like a dog whose master has beaten it and relented: all waggy tail and eager to please. Kroin had not taken my advice and consulted a dentist and could now spit and whistle simultaneously through the new gap in the front of his mouth, a fact that seemed to give him joy. It is easy to amuse a simple mind. He still possessed the limp I had predicted, and I hoped that that wouldn't prove to be a problem; I planned to do some hiking before we saw the last of Ancho.

When the twelve of us boarded the commercial liner to Draconis, we looked more like nursery school conventioneers than anything else. I had instructed the boys in how to dress. They were spiffed up in the latest three-piece suits, complete with diamond cufflinks and gold tie clasps. We had some very expensive forged passports that could pass muster anywhere, but I wanted no overly officious customs officer to have any reason to give us as much as a second glance. There was no telling what crimes these gentlemen were presently wanted for. And aiding and abetting a criminal on Heliox was just as bad as committing the crime yourself. I mean that quite literally. King Caleb had blurred the distinctions normally made among differing crimes on most civilized worlds. The penalty for shoplifting, for instance, was the same as that for first degree murder. It was mandatory execution by firing squad whether you lifted a pack of cigarettes or assassinated the local magistrate.

The liner was nothing like the cruisers that low level businessmen could rent. It was strictly first class and was equipped with Ultradrive. In other words, it got us where we wanted to go in a couple of days instead of a few weeks. The ship was also comfortably furnished. Each of us had a tiny sleeper. During waking hours there was room to move about and there was even a quiet lounge where the lot of us would retire daily for a drink or two. I was surprised at how the roughnecks held their liquor and refrained from bullying or arguing with the other passengers. These boys were barely housebroken, but with those expensive suits, no one would have suspected it.

Draconis was a hub world. Flights to a large number of little-known planets originated here. Ancho was one such destination. In the urban areas surrounding the starport were hundreds of different commercial neighborhoods, each vying to the indigene of a particular planet. Our party headed for "Little Ancho." It was a place of rank smells and urban squalor. Ear-splitting blasts from the horns of busses and ground cars sounded everywhere. Vendors hawked their wares screeching with strident voices, while in hundreds of streetside cafes, busy cusiniers grilled, boiled, and fried an amazing assortment of items, some not generally considered edible elsewhere.

Here, the litter bag was an invention of the distant future. Smoke from the cooking fires rolled over the shops and diners, and rumbling diesel-powered busses pumped out petroleum fumes into the streets. And as the traffic passed, discarded wrappers and papers whirled in the dusty alleyways, settled, and whirled again.

It would not be a comfortable place to live, but we didn't mind visiting at all.

For a reasonable price, we got outfitted in the latest Ancho fashions, which were pretty primitive. For men, the attire consisted of a pair of old-fashioned trousers and an unpressed white shirt. These items were effectively concealed by a large multicolored blanket with a hole cut in its center. The wearer's head protruded

from the hole. We were told by the salesman that it was customary to use the sarape, as this garment was called, as one might use a regular blanket for sleeping in the wilds. For shoes we were offered huaraches , a kind of jury-rigged sandal with tire tread as a sole. They were not particularly comfortable, but I doubted that we'd wear them out in a hurry. Hats also came with the package. They were large and round and woven of straw with a single dingleball hanging from the rear brim of each. They would also be quite useful; Ancho was known to be a hot world.

Lourdes did not at first fare as well as the men in our party. She quickly found herself wearing a hideous black and banana yellow dress with razor sharp pleats over every inch of it. It was a sartorial nightmare. A series of solidly starched petticoats rustled noisily underneath and flared the garment out like some huge open umbrella. And the shoes she was given were high-heels, which made her look as though she were trying to climb out of the dress -- which I guess she was. "Don't say a word," she warned frostily, her raised fist clenched in my face. "If you so much as open your mouth, I'll kill you with my bare hands."

I bit my lip. It took a tremendous effort not to laugh, but somehow I managed it. Soon Lourdes was being fitted for something a bit -- well different. It was a low-cut, deep maroon dress which barely covered her knees and clung to her like honey. The high heels remained a part of the ensemble and were adorned by a pair of black nylon stockings that glistened like silk. The effect of this against the backdrop of her black hair and dark brown eyes was striking.

"That's a definite improvement," I said with a hungry leer. "But there's a name for the kind of woman you look like now, sweetie."

We didn't have to change her attire much to fix things; I confess that I didn't really want to change it all that much. We simply added a ladies' version of the sarape which concealed enough of the dress to keep the wolf whistles under control.

The purpose of the clothing was to thwart any arrangements Colonel Seek might have made to intercept Federal or Alliance busybodies. The last thing I wanted was for us to show up in some dusty port on Ancho decked out in those three-piece suits. If Seek had effected surveillance of the major points of ingress to Ancho, which he might very well have done, twelve well-dressed off-world strangers would be exceedingly conspicuous. I wanted us to look like a gang of backwoods Anchoan entrepreneurs who had been moderately successful in something or other and were well-to-do enough to be taking the occasional interstellar flight.

The only problem was a linguistic one; none of us spoke Spanglo well enough to pass as native. In the University of Centarus IV, I had studied the language along with a half dozen others for an undergraduate degree. I spoke it fluently, yet my accent, would never fool anyone. Aside from that one problem, however, I thought we fit the part well enough to proceed.

We outfitted ourselves with a few Ancho-made knapsacks. Afterwards, we rented rooms in a medium-priced hotel in Little Ancho. The boys from Heliox went out to carouse around the town while Lourdes and I stayed in the hotel and caught up on some long neglected true gravity sleep.

In the morning, I visited the public library. They had a pretty good one here on Draconis, and it was close enough to Ancho to have some current data on the place. I wasn't really sure of what I was looking for. Things had progressed so rapidly on the Seychelles and on Heliox, that I never really had the chance to do the background work that was needed.

There was quite a lot on Ancho in the library: tourist brochures, coffee table books, and histories. I needed up-to-date geological surveys, and there were plenty of them as well. They gave me a pretty good idea of where Seek might want to mine.

His ship, of course, would not be visible. Miles across, the battlesled could never hide behind anything smaller than a planet or large asteroid. For this reason, it possessed cloaking devices that would make it completely invisible. I believed that somewhere on Ancho that great ship sat, its mining tubes buried in the earth beneath it, digging, tunneling, and processing, and concealing the project from all the world. I knew that a magnetic survey or even mass detectors would not reveal the presence of the ship; its stealth technology was too far advanced to permit that. But I also felt that there had to be a way to pinpoint its location.

I evaluated everything I could on the geology of Ancho and found the planet so loaded with likely carnotite mining sites that to investigate them all would take a lifetime. Just the same, I continued research in the library, waiting for inspiration to strike. It did, but only after two days of reading and thinking. I had made my way through half the important historical works on Ancho when I picked up one of the coffee table volumes for a little break. It was a lavishly illustrated tome which dealt with the popular sport of small craft aviation on Ancho. I perused in relaxation, my mission and the revolution completely forgotten, and suddenly it dawned on me how I could locate George Seek.

Five days later, we were already aboard a slow cruiser to Ancho.

CHAPTER SIX

It was a large ship and definitely a budget spaceliner. Most of the passengers were small-time Anchoan businessmen who dressed and cursed like nineteenth century sheepherders and quarreled in loud voices over trifles. They tried to direct some of their complaints to us, but after Biffer gave them an evil stare that was full of menace, they confined their reproaches to members of their own party.

Taking these boys along was already beginning to pay off.

We had more room to move around on this ship, but the week-and-a- half journey to Ancho under standard drive seemed twice as long.

The starport was in a large city called Tecolote. It was one of half a dozen cities with interstellar commerce, but I chose it because I had reasons to believe it might be closest to George Seek. On arrival at Ancho Starport III, we breezed through the crowds and found a cheap hotel where we could all stretch out and relax.

The rooms were clean enough but only because they were hosed out after each vacancy. The floors were cement and each room possessed a drain to aid in mopping up or in the event of accidental flooding. When I looked at the plumbing fixtures, I realized why things were set up this way. Each hosebib, inside and out of the building, was caked with rust and dripped and drizzled away unchecked. This condition was by no means restricted to our low class lodgings; even the swankest hotels were stained red by the oxidizing iron of dilapidated air conditioners and leaky swamp boxes. The faucets in our bathroom were no different. They sat in the centers of large, rusty rings and resembled two lumps of pumice. And when I ran a test on the water in the pipes, I rushed to warn even the iron-stomached Helioxians.

But it wasn't just the plumbing that was substandard. Each time a bus passed on the street below, the entire building quaked and the bedsprings groaned -- and the food and service were atrocious. I found the whole place fascinating; the entire city seemed stricken by the same malady. High and low class alike shared most aspects of this squalor: the unsanitary streets, the crumbling sidewalks, the polluted air, the noise, and the general disorder. Ancho was much like its facsimile on Draconis.

The real thing, however, was bigger and dirtier, and in addition there were many brown-uniformed police in the streets. This, of course, was very much an unsettling difference. The cops gave us the once over whenever we passed, and I felt that they were looking for some pretext to extort some of our cash. Lourdes and I conjectured that we were perhaps too well-dressed for such treatment. Our clothes, though plain, were quite new, and the slightly higher class usually enjoyed some kind of privilege on planets like this.

Lourdes and I took in most of what sights interested us in about two hours and then returned to our room. I hung my hat on the rack inside the door and began unpacking some papers, which I spread out on the floor. Lourdes came over and kneeled down with me on the cement. "This," I said, "is the reason we have come to Ancho via Starport III here in Tecolote."

What lay before me was a series of weather maps printed on nearly transparent onion skin paper so that the daily changing isoglosses could be viewed. It was an odd weather pattern for Ancho. What seemed to be a solid low pressure area had remained over the same geographical area ever since Colonel Seek had disappeared from sight. "This could be the battlesled," I told Lourdes, indicating a roughly circular area some three-hundred miles in diameter. It was an impressively illustrated collection of papers with plenty of overlapping colors and numbers. I had jazzed it up some on the library's color graphics computer.

Lourdes simply leafed through the papers frowning. I did not have the impression that she was deeply impressed. Finally, she sighed, turned the last page, and looked up at me. "It's clear why you insisted on waiting to show me this," she stated tiredly. "I could easily find anomalies more convincing than these. Of course, they would be equally meaningless. About all these papers prove is that you have found a stationary low that is roughly the size of Seek's ship."

"You forget that I have found this anomaly on Ancho," I responded. "And I've found it above a rich layer of carnotite overlying a deposit of the hottest uranium ore on the planet."

Lourdes was not overawed. "If it is the hottest deposit, then it is merely a coincidence," she said, undaunted. "I don't dismiss your ideas without cause; there is a compelling reason to doubt the significance of your observations. It is this: Seek would disguise any weather that could reveal his presence to anyone."

"Would he?" I asked. "I folded my papers up and tucked them back in my suitcase. "Do you honestly think anyone would attribute a stubborn low pressure zone to the presence of a P-657?"

"Yes," Lourdes answered, with a smile. "You would. So, there's your answer. Seek would leave no traces of his position. Why would he if he didn't have to?"

I took a folder from the suitcase and opened it. It contained several pages photocopied from the coffee table volume on small aircraft. I handed it to her. She looked at the documents for a few moments without joy and handed them back. "Tell," she finally replied.

"What do you remember about the weather maps you just viewed?" I inquired. I motioned toward my suitcase. "Tell me from a small aircraft pilot's point of view."

Lourdes began counting off on her fingers. "Winds 55 knots, with conditions prime for airframe icing, not to mention carburetor ice. Instrument flight rules every inch of the way, wind shear, too, and the density altitude around that low would give a small plane all the flying characteristics of a grand piano. In all, I'd say really delightful."

"Fine. What would happen if a private airplane tried to navigate through weather like that on Marion? Assuming, of course, that private aviation is still permitted under the present Federal occupation." I asked.

Lourdes shrugged, obviously getting bored. "It could easily turn up missing. A civil patrol would be sent out to investigate. The regular full investigation would ensue."

"Aha!" I shouted. "That's exactly what George Seek would want, isn't it?"

"Don't be sarcastic," Lourdes replied, annoyed. Clearly, that is the exact opposite of what he would want -- but that won't happen because..." She broke off, realizing what she was about to say.