Through

the dining

room windows

of the Douglas

Lodge, Lake

Itasca glows

in the morning

mist, a deep

pool of memory

my brother and

I have come

here to tap.

It’s been

thirty-five

years since

I’ve been

back, but time

here has

frozen. The

breakfast

plates drip

with buttery

hash-browns,

eggs and

bacon,

sausages and

pancakes as if

it were still

1963, not

mid-July,

2001. In

ordering a

bagel I’ve

committed a

faux-pas. It’s

been savaged

in the kitchen

in response to

my sin, basted

with a pastry

brush and now

stares up at

me, sodden

with butter, a

packet of

cream cheese

on the side.

I remember the

story my

brother, Tom,

told me of his

visit here one

year ago, how

on entering

the gift shop

with our

brother,

Steve, the

cashier had

looked up and

said with

conviction,

“You’re the

Coles,” had

looked right

past their

graying hair

and burly

forms and,

peeling back

the years, had

seen before

her two young

boys, the

faculty kids

who would come

from Arizona

to these

Minnesota

woods when the

biology

station opened

in June. And

so it’s been

everywhere we

turn—the

culvert, the

graveyard, the

bathing beach,

the crappie

hole—an eerie

stasis,

memories

surfacing as,

years before,

my father

would haul up

his dredge,

uncovering

from the lake

bottom fairy

shrimp,

daphnia,

copepod.

Now, we’re

here for birds

as well as

memories. We

head back to

our room for

our field

glasses,

butter and

wood smoke

scenting the

air. Inside,

we gather

field guides

and notebooks,

hang

binoculars

from our

necks, and set

out from our

spartan room,

narrow twin

beds, a

dresser, a

fan, and no

TV. Were there

one, I’d be

tuning in CNN,

as I’ve been

doing all

month long,

following the

search for

Chandra Levy

through the

urban wilds of

Washington.

The TV images

fill my head,

policemen

fanning out in

Rock Creek

Park;

corpse-sniffing

dogs searching

boarded-up

buildings;

Chandra,

smiling from

the dining

room table;

Chandra, eyes

closed, curls

entangled on

her mother’s

head; Chandra,

twenty-four

and maybe

alive. Our

search is more

hopeful. Last

year Tom saw

the

chestnut-sided

warbler, a

true

life-lister,

and now wants

me to see it

too. We know

it’s out

there, but

patience and

diligence and

plain dumb

luck will

determine if

it makes my

morning list.

We begin at

our old

haunts, the

faculty cabins

and the long,

straight

walkway past

the student

cabins to the

dining hall.

Here, we spent

hours playing

ping-pong and

listening to

Rubber Soul

back in 1963,

five Cole kids

and our close

companion,

Bill

Underhill, son

of an

ichthyologist

from St. Paul,

a strong,

lanky teen who

moved between

my preteen

brothers—fishing,

boating, and

roaming the

woods—and my

teenaged

sister and me.

Bill

life-guarded

at the bathing

beach, Bill

introduced us

to bog and

fire-tower and

Yeti lore.

Bill gave us

his picture,

bare-chested

in his cabin,

lifting

weights. I

have it still,

the sinewy

boy, face

contorted with

the strain.

His memory

infuses this

place.

There’s a bend

in the park

road that

calls up for

Tom every time

we pass it

Bill’s

encounter

there with

some young

hoods. “I was

sitting right

there,” Tom

recalls. “I

thought there

would be a

fight, that

Bill was so

tough.” But

when the hoods

demanded,

“Where’re you

from?” Bill

swaggered,

then fizzled:

“What’s it to

you? St.

Paul.” All

these years

we’ve

remembered

that retort,

Tom, as if it

were happening

before him,

and I, as it

was told to

me, Bill’s

bravado. Then,

one Christmas,

a card arrived

from the

Underhills,

“Have you seen

Bill?” He had

left a party,

headed home to

St. Paul, then

turned up

missing.

“Please call

us if you hear

from him.” And

then, the next

year, a

Christmas card

with the same

request. And

then nothing

more.

Now, Tom has a

kingbird in

his sights. I

raise my

glasses to the

spot and fall

into the

rhythm of

birding,

scanning the

canopy,

zeroing in,

calling out

coordinates

then, finally,

looking in

tandem. We see

red-breasted

nuthatches

spiraling down

pine trees;

song and

chipping

sparrows; cat

birds, like

mockingbirds

in yarmulkes;

great blue

herons;

ring-billed

gulls and

cedar

waxwings; barn

swallows in

frenzied

flight; black

ducks with

chicks; an

immature bald

eagle and,

bright against

the foliage, a

scarlet

tanager. We

check each

bird against

the drawings

in our field

guide, confirm

its markings

and its range,

then press a

mental “Enter”

key to file it

away. In

birding, I

realize, much

of the

pleasure is

after the

fact—the

checking and

recording—as

Tom and I will

do tonight

over Summit

Ales, writing

in our

notebooks this

first “day’s

list” then

three day’s

hence our

consolidated

“trip lists”

and finally,

at home alone,

our now

enhanced “life

lists,” each

new bird

recorded in

the back of

our field

guides until

one day,

ideally, we’ll

have seen them

all. Birds,

unlike people,

require but

one sighting.

If we fail to

see the

chestnut-sided

warbler, if

every

chestnut-sided

warbler

vanished

suddenly from

the earth, Tom

would still

have it,

marked on his

life list,

written in

stone.

Our wanderings

have brought

us to the

faculty cabins

where we meet

two biologists

coming from

the dock. They

know of our

father and

tell us the

news: Jim

Underhill has

died. I

register the

details—cancer,

last

August—but am

jarred by the

symmetry. One

man, like my

father, is

from ASU; the

other, like

Jim, from the

U of M. They

could be our

own fathers,

thirty years

back, Bill’s

and ours, who

had stood on

this very

spot, speaking

in their

summer tongue,

a Latiny

jargon, as

we’d run by.

And strangely,

before these

men, Tom and I

remain faculty

kids, though

we’re ten

years their

seniors, at

home are

faculty

ourselves. In

the pause that

follows I ask

the

Minnesotan,

“Did they ever

find out what

happened to

Bill?” He

stares at me

blankly. “His

son,” I add,

“who vanished

in the

sixties.” “I’m

sorry,” he

answers, “I

hadn’t heard

about that.”

And I am truly

shocked—that

Bill’s story

had been

swallowed up

with him, his

slate wiped

clean,

especially

here at Lake

Itasca where

bends in park

roads play

back voices

and clerks see

visions of our

childhood

selves;

especially

now, with

Chandra’s

mystery

filling the

airwaves and

newsmen

dredging up

the long-cold

case—Jimmy

Hoffa, Etan

Patz, Amelia

Earhart,

Ambrose

Bierce—or the

merely cool:

Jill Behrman,

who went for a

bike ride in

May of 2000

and never came

back; Matthew

Pendergrast,

whose SUV,

clothes,

wallet, and

money turned

up last

December in an

Arkansas

swamp,

everything but

him. How,

then, could

Bill’s name

ring no bells,

not even in

the halls of

his father’s

department,

not even by

the shores of

this mnemonic

lake?

Feeling

awkward, we

change the

subject to one

as dear to us

as Bill and

warblers:

Cabin Four,

our old summer

home. It

appears to be

vacant; do

they think we

could go

inside? They

tell us what

we long to

hear: not only

is it vacant,

it’s unlocked.

It’s as if

they’d

announced an

extraordinary

sighting—the

red-cockaded

woodpecker,

the

coppery-tailed

trogon. We’re

off in a flash

to revisit

Cabin Four.

As the door

swings open,

whole decades

dissolve.

Inside it’s

still the

sixties, the

same log

walls,

fireplace,

tiny bathroom,

and

two-bedroom

loft where we

children

slept. It’s

all still

present, Jeff

sleepwalking

on the

balcony, our

father calling

out the

species as a

bird sounds

from the

thicket, the

boys at

midnight

throwing

pillows at an

errant bat,

our mother,

heading out

for groceries

in Park

Rapids. For

her, these

summers must

have felt like

golden times

that she could

bottle up and

carry with

her. In the

late seventies

she made a

cardboard

replica of

Cabin Four,

then built the

real thing

with my father

and anyone

who’d come to

help outside

Flagstaff,

Arizona, their

retirement

home.

Now, these

rooms

transport me

in space as

well as time.

As I gaze up

at the

balcony, I

feel both lake

and mountain

at my back;

upon turning

feel as likely

to see, black

before me, the

slopes of Mt.

Humphrey as

Itasca’s

shores. And my

children, I

think, who’ve

never seen

Itasca, but

summered in

Flagstaff,

would bask

here as I do,

in this

cabin’s glow,

pre-Vietnam,

early Beatles.

It’s been an

eventful day,

despite that

gap on our

morning

list—the

chestnut-sided

warbler—its

slot more than

filled by

Cabin Four.

And the next

days continue

true to form.

In the

graveyard

through a

light rain, we

see

white-breasted

nuthatches,

eastern wood

peewees, downy

woodpeckers,

chimney

swifts, a

yellow

warbler, an

American

redstart, a

red-shafted

flicker, a

black-capped

chickadee, and

a red-eyed

vireo. Down a

lonely back

road toward

the Loonsong B

& B, we

pick up ticks,

and a

rose-breasted

grosbeak,

then, yellow

through the

high grass, an

American

goldfinch. By

an old cabin

in the park,

Tom calls out

a bird I’ve

never seen,

the

Blackburnian

warbler, as he

does so

recalling the

words of our

father who

said of some

naturalist,

Tom forgets

who, “He saw

the

Blackburnian

warbler, and

it changed his

life.” Tom

repeats the

quote. And in

its cadence I

too hear my

father’s

voice, “Bring

the glasses to

your eyes,” a

birding

fundamental,

while sensing

how feeble my

memories are,

how sparse,

compared to

Tom’s, which

form a rich,

dense foliage

through which

we peer. For

three days in

fact, as much

as looking

I’ve been

listening to

the voices

that Tom

replays: the

cashier’s, my

father’s,

Bill’s, and

even Jim’s.

Our last

summer at

Itasca, after

Bill’s

disappearance,

Tom remembers

asking Jim if

they’d heard

from him and

his chilling

reply, “We

don’t expect

to be hearing

from Bill,”

hope, like

some lost

lure, sunk in

the profundal

ooze.

Our time

running out

here, we

wander down to

the dock at

dusk and watch

the fireflies

floating

through the

cattails. A

loon calls

from across

the lake,

haunting and

distant. I

remember the

summer before

when, sleeping

on the roof of

the Flagstaff

house, I awoke

to coyote

cries in no

way dog-like,

impossibly

high-pitched,

wild and

manic, “like

laughter,” I

had thought

then, “almost

like loons.”

And as I tell

Tom this

story, the

loon sounds

again, but

this time I’m

hearing

coyotes; then

unmistakably

it’s the loon,

until Tom

solves the

mystery: it’s

both coyotes

and a loon,

the dog pack

answering the

lonely call,

our two Cabin

Fours

distilled into

sound.

Sunday morning

at the Douglas

Lodge, our

last buttery

breakfast

consumed, our

bags

half-packed,

we decide to

spend our

final hour

here birding

in a leafy

grove just

beyond the

dining room.

As I’m zeroing

in on a

yellow-bellied

sapsucker, Tom

cries, “There

it is. That’s

it. The

chestnut-sided

warbler.” And

for five slow

minutes it

lingers in our

view, weaving

in and out of

leaves, but

staying in one

tree,

perfectly in

focus, at one

point,

obligingly,

hopping onto a

leafless

branch and

turning to

expose its

chestnut

streak. This

is just too

much, I think,

this plum of a

sighting, here

at the

eleventh hour,

life, as it

often does,

mirroring art:

loose ends

tied up; in

the final

chapter,

quests

fulfilled. And

were this trip

a text, I know

what would

follow: our

warbler

sighted,

Chandra would

be found, as a

necessary

adjunct to its

design. But

this is life,

where all is

random, this

sighting mere

coincidence,

its timing

pure

irrelevance,

on this July

day, in these

Minnesota

woods, on this

small blue

planet

hurtling

through space.

Walking back

to our room

with Tom, I

think of

Chandra, and I

think of Bill,

of open ends

and hanging

threads, of

mystery and

hope and faith

and the wisdom

sometimes of

letting go.

But there’s

something

bothering me,

one thing I

have to know.

I wonder all

the way

through the

car ride to

the airport,

and all

through the

plane ride

back to New

Orleans,

through the

parking garage

and the car

ride home,

through the

piled-up

papers and the

wagging dog.

Once inside I

boot up my

computer and

punch in the

words,

“Minneapolis

Star,” select

“Archives,”

“Obituaries,”

“August,

2000,” “James

Underhill.”

Then I skim

through the

praises of

colleagues,

“an exemplary

role model,”

“an avid

gardener,” “a

first-class

guy,” and

those of Mary,

a daughter

whom I don’t

recall: “sharp

wit and

banter,”

“warm,

generous and

compassionate,”

“We’d call him

our

Renaissance

man.” But what

I really want

will be below.

I scroll to

the bottom and

find what I

feared I

would: “In

addition to

his daughter,

survivors

include his

wife, Anne of

St. Paul, and

another

daughter,

Sarah Holm of

Radisson,

Wisconsin.”

How could no

one have

thought to,

have needed

to, write Bill

down?

It’s late, but

I’m wide

awake. I file

away my

document and

print up a

copy to send

to Tom. Then I

walk the dog,

sift through

the mail,

peruse the

headlines, and

turn on CNN.

Unpacking my

field guide, I

flip to the

back and look

up my two new

birds, the

chestnut-sided

warbler and

the warbler

that changed a

man’s life.

With my

blackest pen,

in my finest

hand, I write

them both

down.

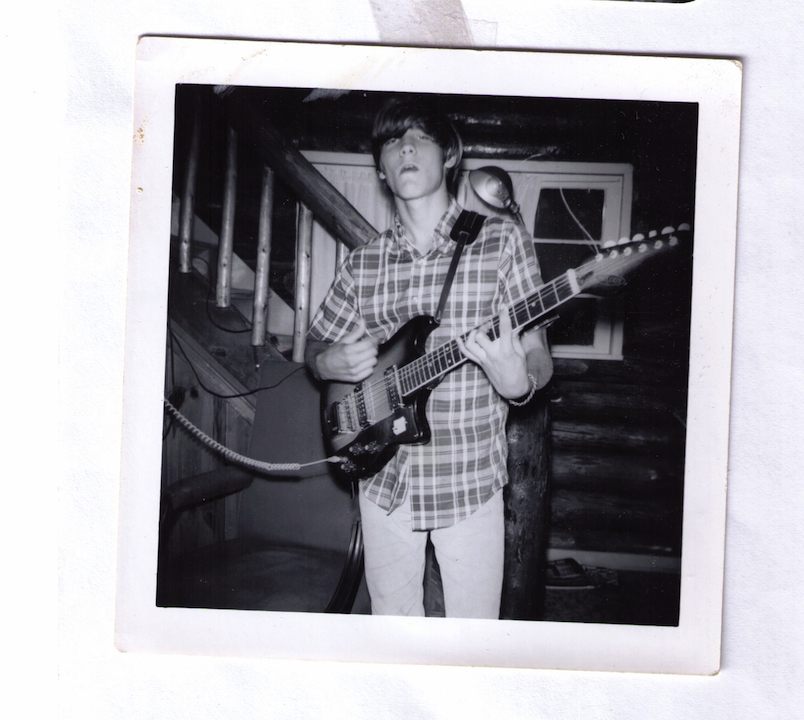

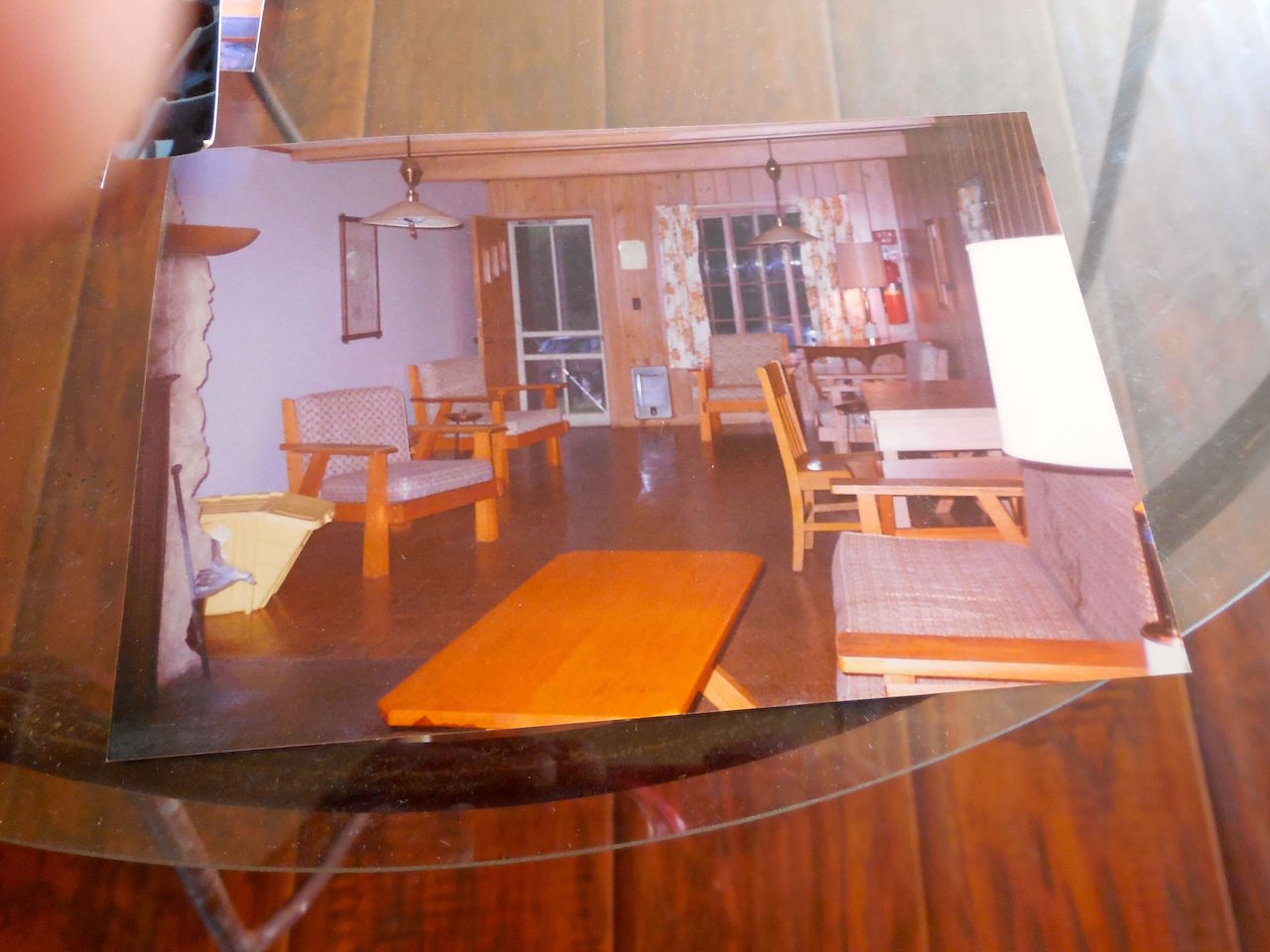

Cabin

4 itasca

bedroom.jpg

tom

guitar itasca

cabin four.jpg

tom

guitar itasca

cabin four.jpg

Cabin

4 sally stairs

itasca.jpg

Cabin

4 sally stairs

itasca.jpg

Cabin

4 itasca

Tom.jpg

Cabin

4 itasca

Tom.jpg

Cabin

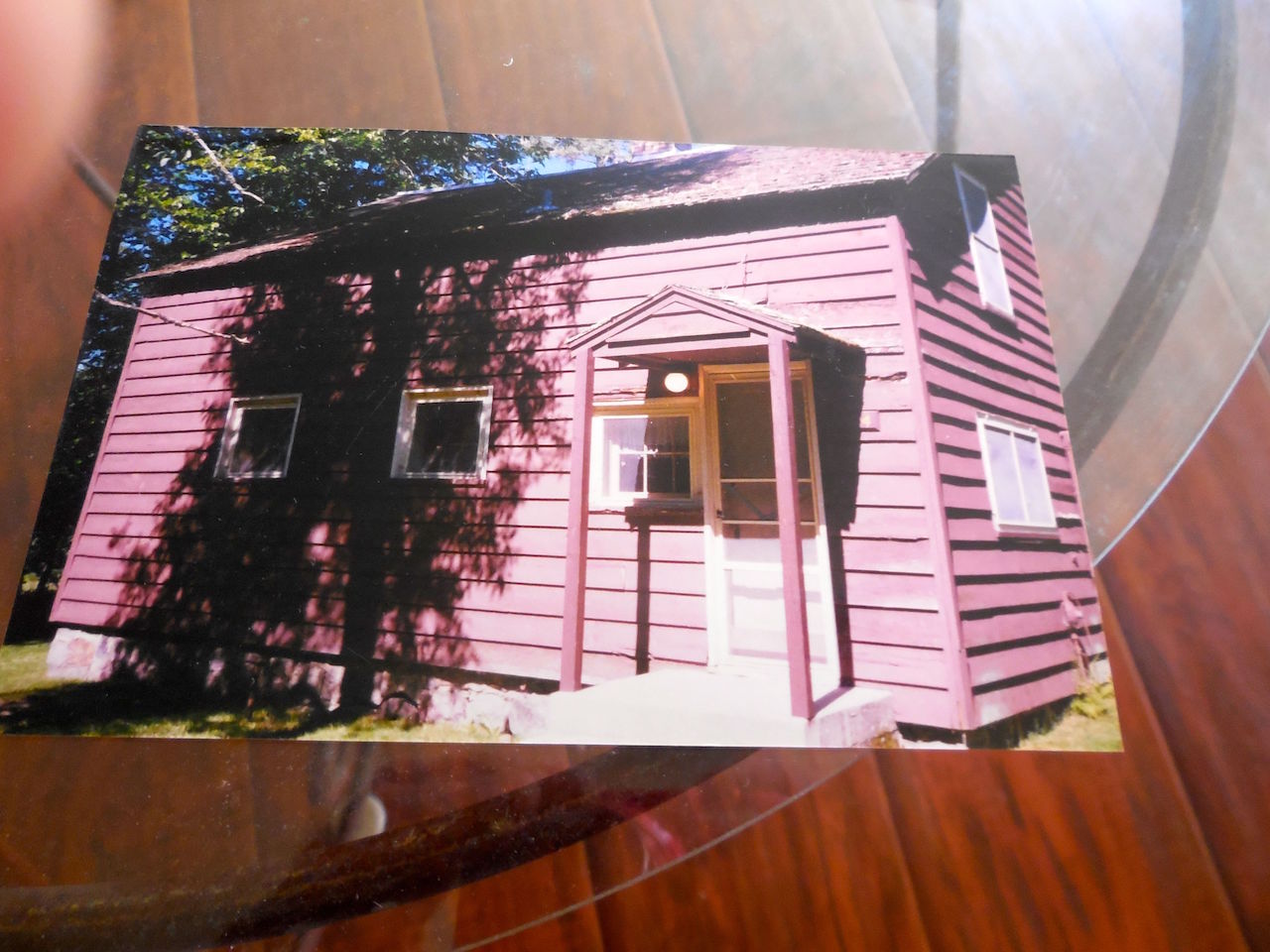

4 Itasca

outside.jpg

Cabin

4 Itasca

outside.jpg

Cabin

4 Itasca

Kitchen.jpg

Cabin

4 Itasca

Kitchen.jpg

Cabin

4 Itasca 2001

Sally

fireplace.jpg

Cabin

4 Itasca 2001

Sally

fireplace.jpg

Cabin

4 Itasca Sally

on balcony.jpg

Cabin

4 Itasca Sally

on balcony.jpg

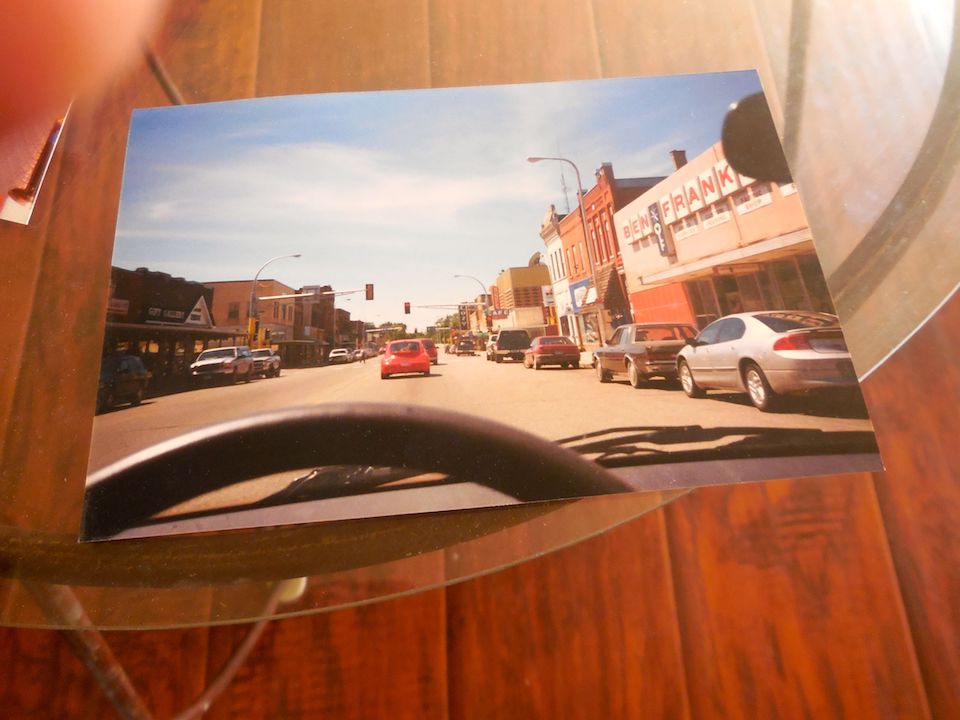

Park

Rapids Itasca

trip 2001.jpg

Park

Rapids Itasca

trip 2001.jpg

Park

Rapids Itasca

trip

2001-2.jpg

Park

Rapids Itasca

trip

2001-2.jpg

Reading

Room

Itasca.jpg

Reading

Room

Itasca.jpg

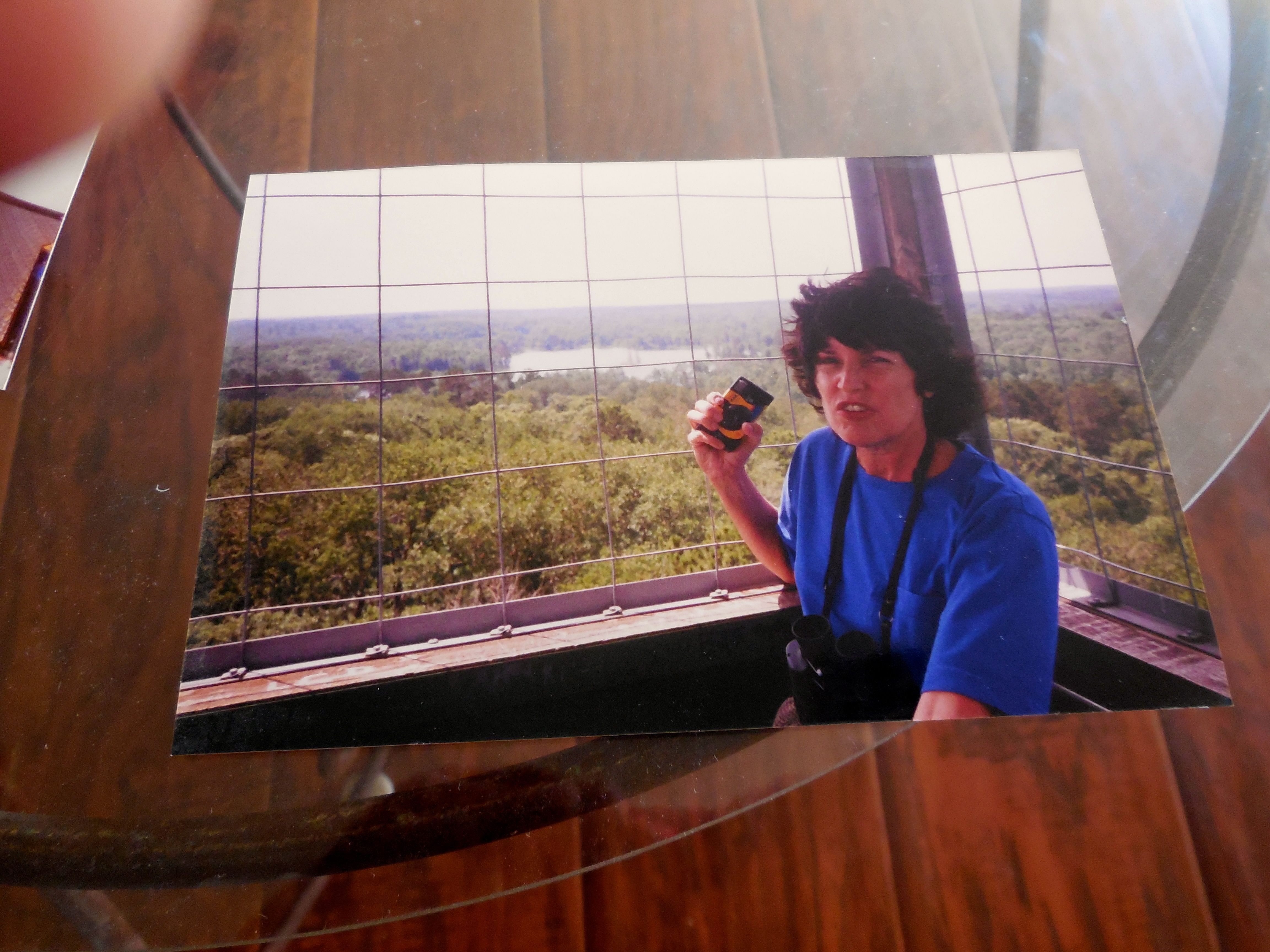

Sally

Itasca

2001-2.jpg

Sally

Itasca

2001-2.jpg

Sally

Itasca

2001.jpg

Sally

Itasca

2001.jpg

Squaw

Lake Sally

Itasca

2001.jpg

Squaw

Lake Sally

Itasca

2001.jpg

white

pine.JPG.jpg

white

pine.JPG.jpg

|