19. La caída

Por regla general, la gente no tiene la

capacidad de recordar mucho de lo que le ha

pasado antes de la edad de cinco años. No

obstante, me acuerdo muy bien de lo que me

ocurrió un día cuando debía de tener unos cuatro

años. Me caí de un carrito de compras y me pegué

en la cabeza contra el piso duro de una tienda

de abarrotes que se llamaba El Mercado Weiss.

No me acuerdo de la caída, ni del viaje al

hospital. Sin embargo, recuerdo el sueño que

tuve cuando estaba inconsciente. Había dos filas

de hombres y mujeres vestidos en casacas

blancas. Los de una de las filas me sostenían

las manos y los de la otra los pies y me

rebotaron de uno en uno por un pasillo largo

hasta que, por fin, llegué a la oficina del

médico que me frotó la rodilla con un polvo

verde.

"Qué raro," me decía yo, "que haya puesto el

polvo en la rodilla sabiendo muy bien que el

accidente me hizo daño en la cabeza.”

Recobré conciencia y el médico me dio una

linterna y me enseñó a prenderla y apagarla.

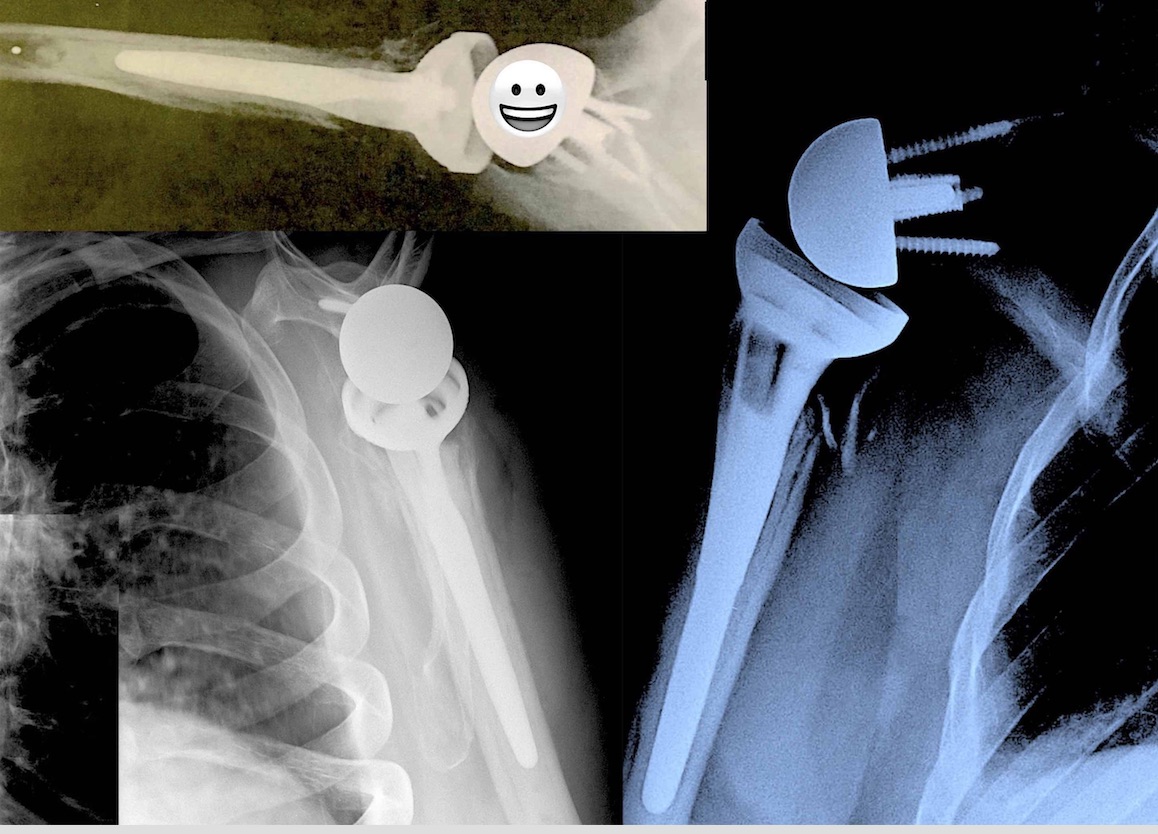

MI HOMBRO

CÍBORG

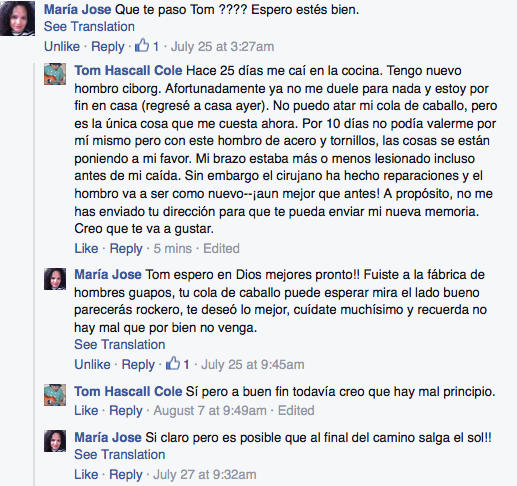

En junio de 2015 hice una audición para

una actuación en un bar que está a unos cuatro

bloques de donde vivo. Toqué la guitarra y

canté por dos horas y parecía que a ellos les

gustaba porque después me contrataron para

actuar durante la tarde del 4 de julio en la

que iban a tener una fiesta especial.

No iba a poder asistir.

Al llegar a casa, puse mi equipo de sonido en

la cocina. Yo no tenía ganas de guardarlo

porque hacía un año y medio me había caído de

mi bicicleta y me hice daño en el hombro.

Todavía me dolía un poquito. Yo había tenido

terapia, pero no me podían ayudar y al fin

tenía que hacerme una resonancia magnética.

El procedimiento resultó increíblemente

doloroso. Sabía que me iban a meter en un

cilindro blanco que parecía de porcelana y

había oído que los pacientes frecuentemente

tenían una sensación terrible de claustrofobia

al meterse dentro. No creía que eso me

pasara a mí. Me equivoqué.

¡Era como ser cargado en un cañón de cabeza!

El técnico me mostró que los dos extremos del

cilindro estaban abiertos y al saber esto me

pude relajar un poquito.

Por supuesto la claustrofobia no era dolorosa.

Era otra cosa. Si yo no movía el brazo,

empezaría a dolerme y durante el procedimiento

el técnico no me permitía moverme en absoluto.

El dolor aumentaba.

Había un altavoz en el cilindro y cuando el

técnico me preguntó cómo estaba contesté:

—¡Me estoy muriendo!

—Solamente le faltan diez minutos. No se

mueva.

Creía que iba a morir.

Después la médica me mostró el resultado que

estaba en una pantalla aunque confieso que yo

no podía entender lo que veía. Me dijo que se

me había desgarrado un tendón y que estaba

fuera del alcance de ningún cirujano

arreglarlo.

—Las buenas noticias son que puede continuar

andando en bicicleta —me dijo—. Porque en caso

de que se caiga de ella otra vez no es posible

hacerse más daño allí.

—¿No hay nada que se pueda hacer? —le

pregunté.

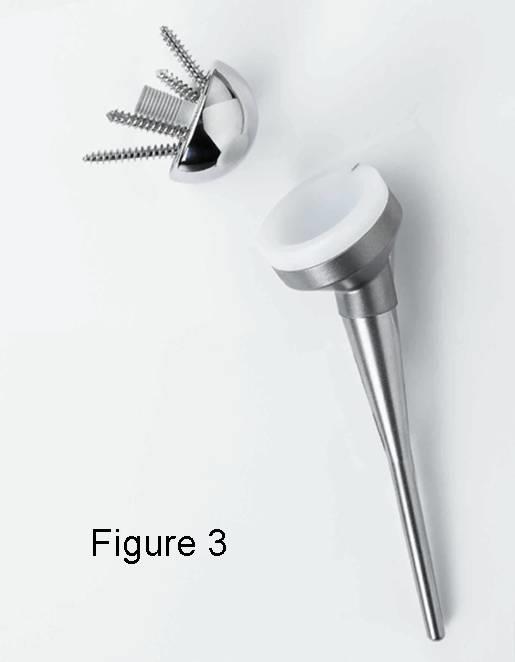

—Bueno, se podría reemplazar el hombro entero.

Yo creía que se estaba refiriendo a un

reemplazo de los huesos de un cadáver y no

quería tener nada que ver con eso.

—Hay otra cosa —ella dijo—. Tiene dos tendones

desgarrados, pero uno parece ser una herida

vieja y los músculos alrededor de él están

atrofiados.

No recordaba haberme hecho daño en ese hombro

antes.

El hombro me dolía mucho, pero podía tocar la

guitarra en un bar los miércoles y cuando pasó

un año el hombro dejó de dolerme tanto como

antes.

En aquel día de junio yo miraba el equipo en

la cocina. Había dejado unos grandes altavoces

y el amplificador y otras cosas en la parte

central de la cocina por donde de costumbre

pasaba y me dije, "Tom, vas a tropezar con

ello".

Esa noche a las once y veinte, yo apagué las

luces, pasé por la cocina, tropecé con el

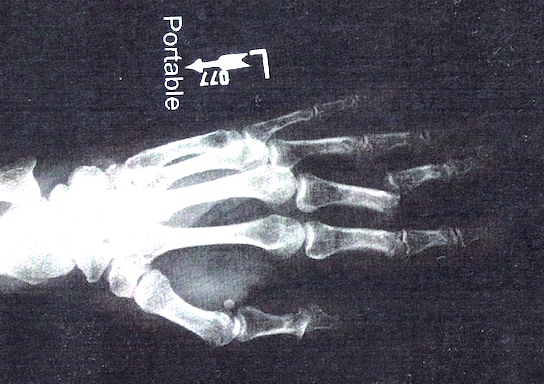

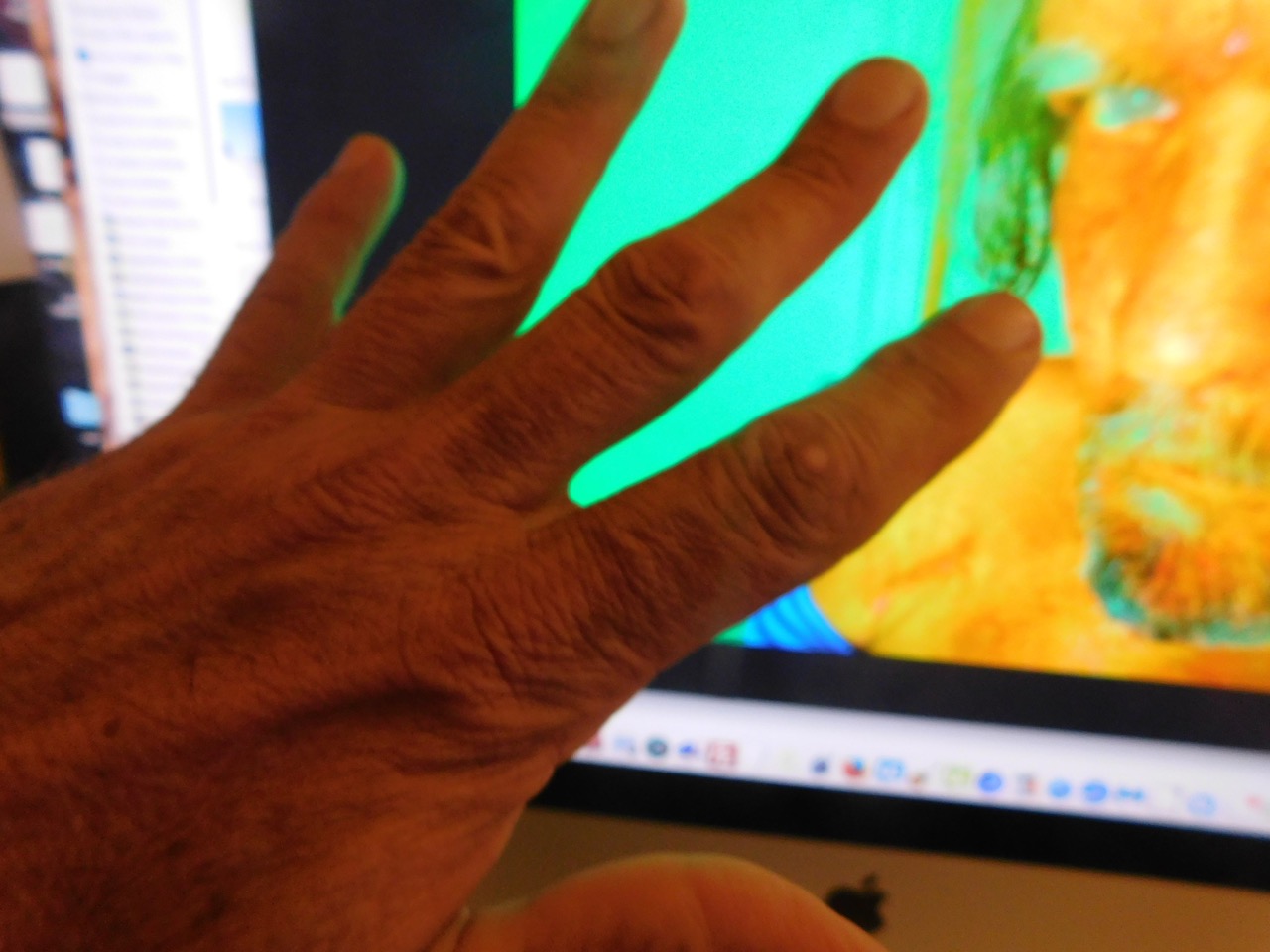

equipo y me rompí dos dedos y mi hombro.

En ese momento no sabía que me había roto el

hombro. Me dolía, pero siempre lo hacía. Lo

que me preocupaba eran los dedos, uno de los

cuales se había dislocado y estaba apuntando a

la izquierda. Era totalmente espantoso.

Llamé a mi hermano y me dijo que marcara el

911. Lo hice y los bomberos acudieron a mi

casa. Llegaron con su camión de gancho y

escalera y su ambulancia que yo siempre

llamaba "El Taxi de Lagos del Sol".

Los bomberos me parecían un poquito aburridos

con todo. Me sorprendió que no me hablaban

mucho y no me ofrecían palabras de ánimo. En

el pasado había sido muy impresionado al ver

el profesionalismo de otros bomberos y la

manera de la que aseguraban a personas

heridas.

—¿Tiene dolor en otro sitio? —preguntó un

bombero mirándome la mano.

—Bueno —contesté—. El hombro me duele un

poquito.

Me llevaron al hospital donde me cortaron la

camiseta favorita con tijeras y la doctora me

preguntó:

—¿Me da permiso para colocarle el dedo?

Yo asentí con la cabeza y ella dijo que yo

tenía que contestarle con palabras.

—¿Por qué? —le pregunté.

—De vez en cuando se quiebran.

—Sí, entonces —le dije—. Tiene permiso.

Ella se acercó a mí, agarró el dedo y empezó a

tirar.

Yo empecé a gritar.

Mi hermano me dijo que desperté a cada

paciente en ese piso del hospital.

—¡Ella tenía agallas! —dijo mi hermano más

tarde.

El dedo no se quebró.

Usualmente cuando una persona se rompe un

hueso, el médico se lo puede colocar y enviar

al paciente a casa con su brazo o pierna en

una escayola. Para mí no iba a ser así.

Tenían un aparato semejante a una máquina de

resonancia magnética (No se exactamente lo que

era). y me escanearon el cuerpo con él.

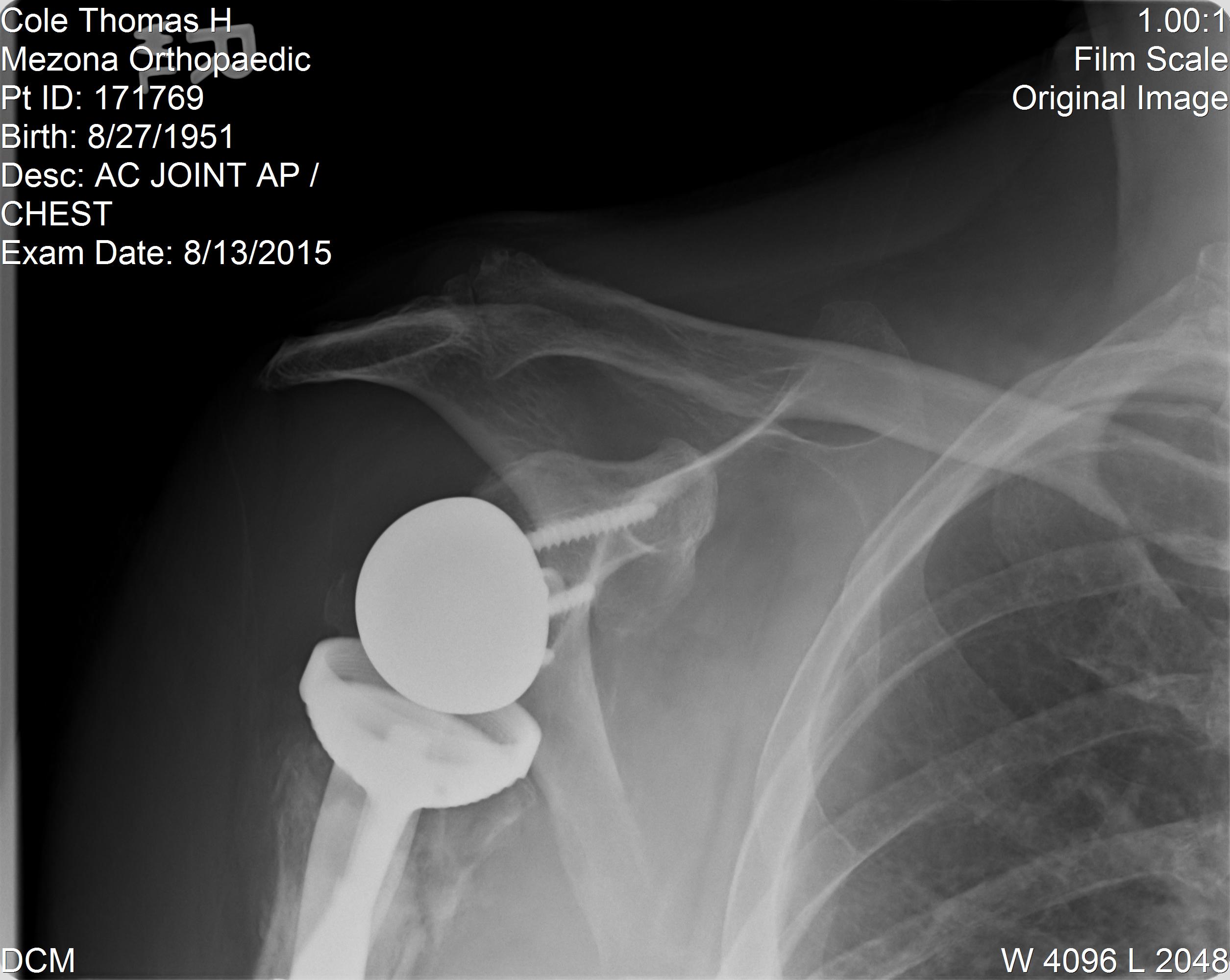

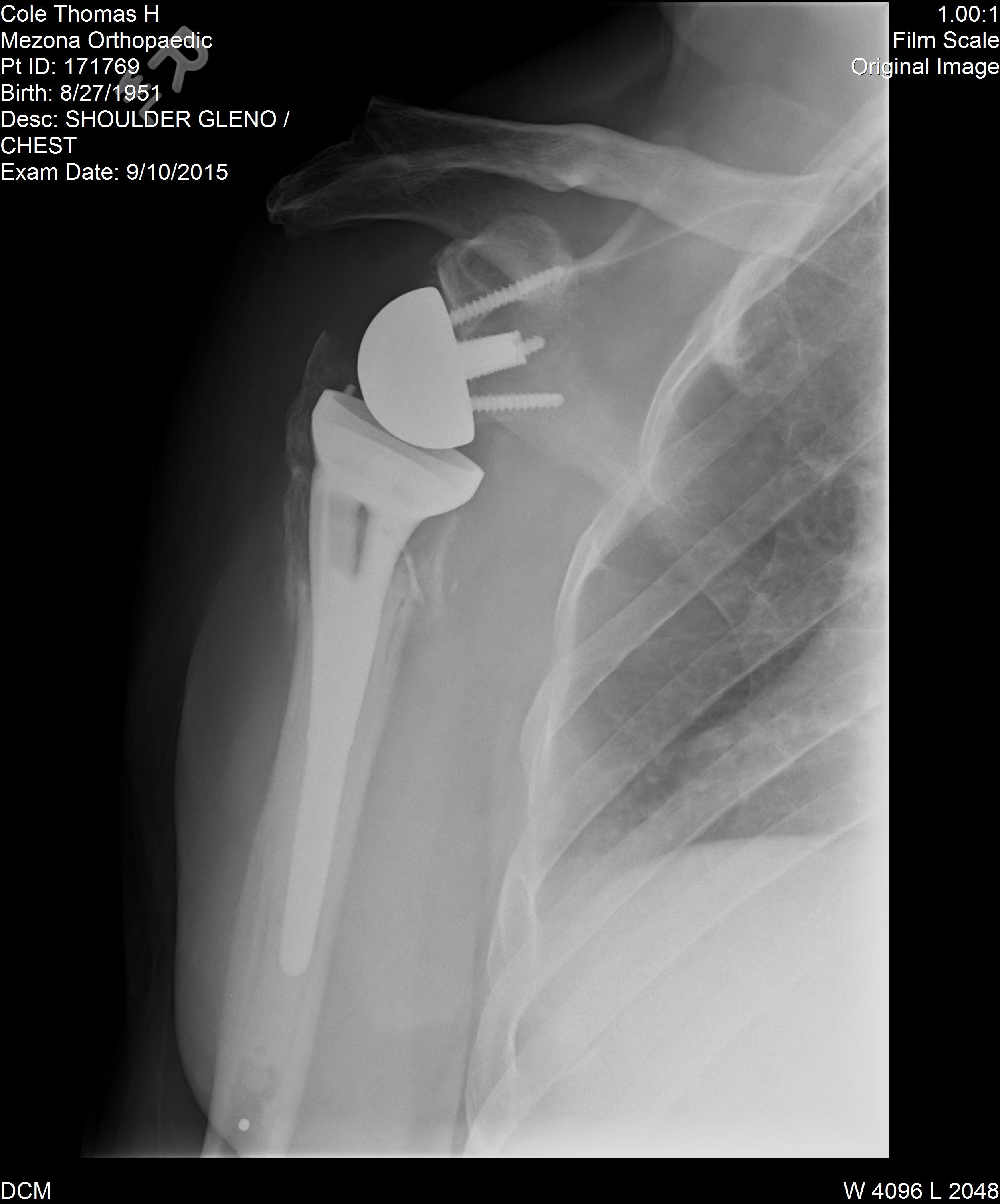

—Dicen que te has roto el hombro —me dijo mi

hermano—. Es malo y tienes que tener un

reemplazo.

Me pusieron la mano en una tablilla y el brazo

en un cabestrillo y me enviaron a casa esa

misma noche. Tenía que esperar diez días antes

de la cirugía. Mientras tanto, fui a ver a un

especialista de manos, un doctor que me dijo:

—Estos dedos te van a dar más problemas que el

hombro mismo.

Me advirtió que lo que tenía era una herida

que típicamente producía rigidez en la mano y

que muy probablemente no iba a poder tocar la

guitarra más.

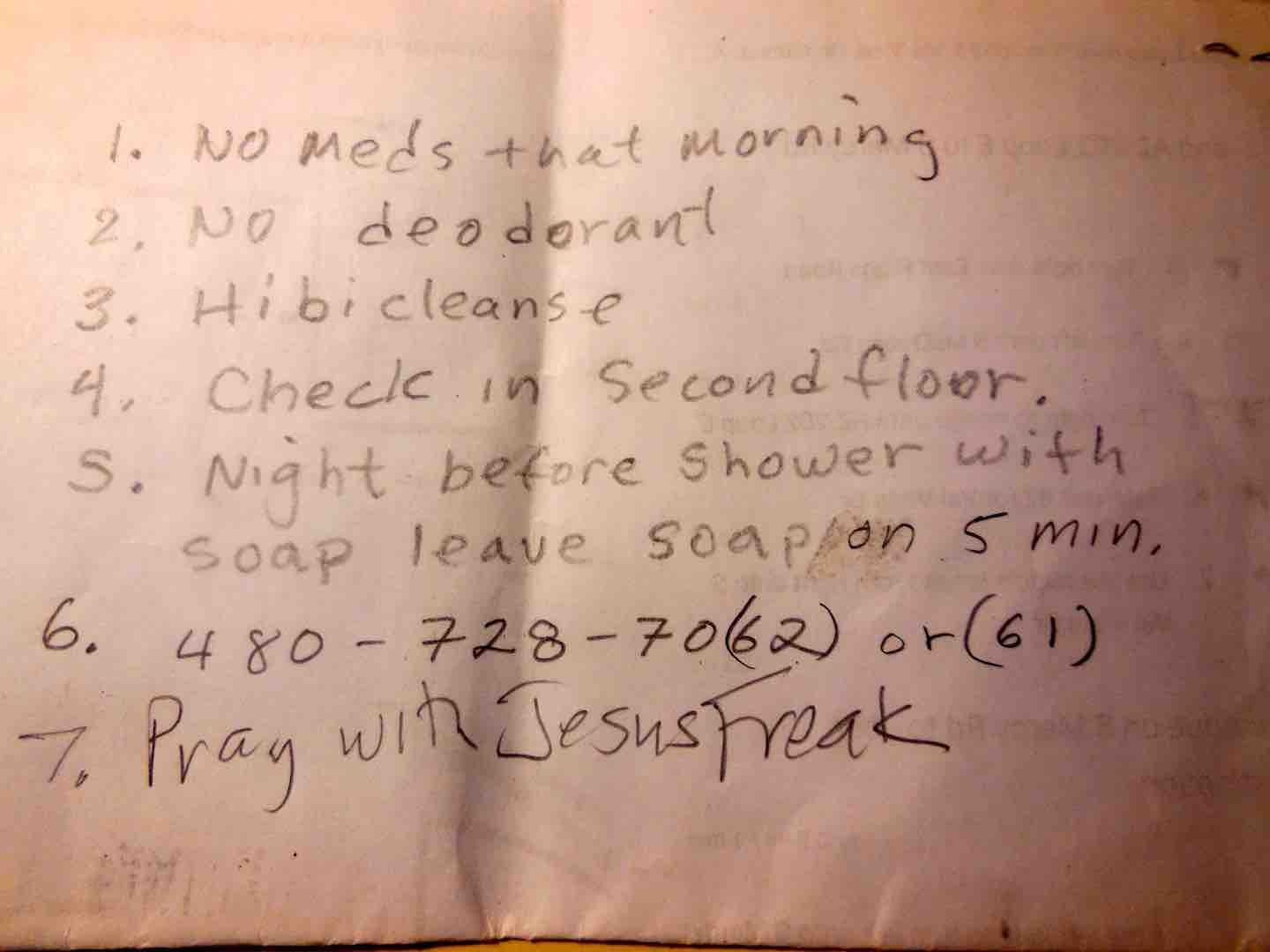

Mi hermano habló con el cirujano ortopédico

que le dio las directrices que yo tenía que

tener antes de la cirugía. Escribió: 1. no

medicamentos esa mañana 2. no desodorante...

Llegué al hospital bien preparado el día de la

cirugía. Antes de la operación yo estaba en la

cama y mi hermano estaba en el cuarto también.

El anestesista me explicaba lo que iba a

pasar. Luego dijo:

—Vamos a orar.

Nosotros nos enfadamos instantáneamente y

gritamos a la vez:

—¡¡NO!!

En este instante, el anestesista se dio cuenta

de que su egoísta intento de engañar y

manipular había fracasado. Lo teníamos

calado y bien lo sabía.

No me acordé de otra cosa.

Lo que escribí en mi libro Las misteriosas

noches de antaño, ilustra la razón por la que

nos enfadamos tanto. Trata de lo que pasó

cuando mi madre estaba muriendo de cáncer.

Un pastor de no sé dónde se presentó. Era como

los otros zopilotes de su tipo que siempre

vienen para posarse en los árboles cuando

alguien está enfermo.

Mi madre de cortesía dijo que él podría hablar

con ella (a solas).

Después, yo hablé con mi madre que me dijo que

le había dicho a ese pastor que no era

cristiana, pero a él no le importaba. Ella

estaba muy débil y ese clérigo sabía que podía

aprovecharse de ella. Le tomó la mano y empezó

a orar a Jesucristo.

Yo fui en busca de él y pensaba matarlo muy

lentamente con mis propias manos.

Afortunadamente para ese cerdo religioso, se

había marchado saliéndose con la suya.

No quería que mi madre pasara su última día

en el mundo siendo la víctima de tal

predador y al despertar de la cirugía yo

estaba empeñado en que ese anestesista jamás

escapara de mi ira.

Pero tardé mucho en despertar. Puede ser que

ese anestesista me hubiera dado una dosis

doble de anestesia para que yo no recordara lo

que intentó hacer.

Soñé con una enfermera. Era una hembra y

morena versión de Brainiac V9 que se sentaba

en un asiento girando delante de una pantalla

que chispeaba. Yo tenía dolor, pero como ella

me estaba leyendo los pensamientos ya lo sabía

antes de que se lo pudiera decir y ella dijo

que ya había enviado el analgésico. El azul de

sus ojos chapoteó sobre la pantalla.

Pasaron horas.

Antes creía que alguien me iba a avisar: "Ya

ha tenido la operación". como siempre se hace

cuando alguien ha tenido pentotal de sodio y

no ha tenido el sentido de que el tiempo haya

pasado. Pensaba que tendría un despertar

repentino.

Me dijeron que mi sobrino me visitó, pero no

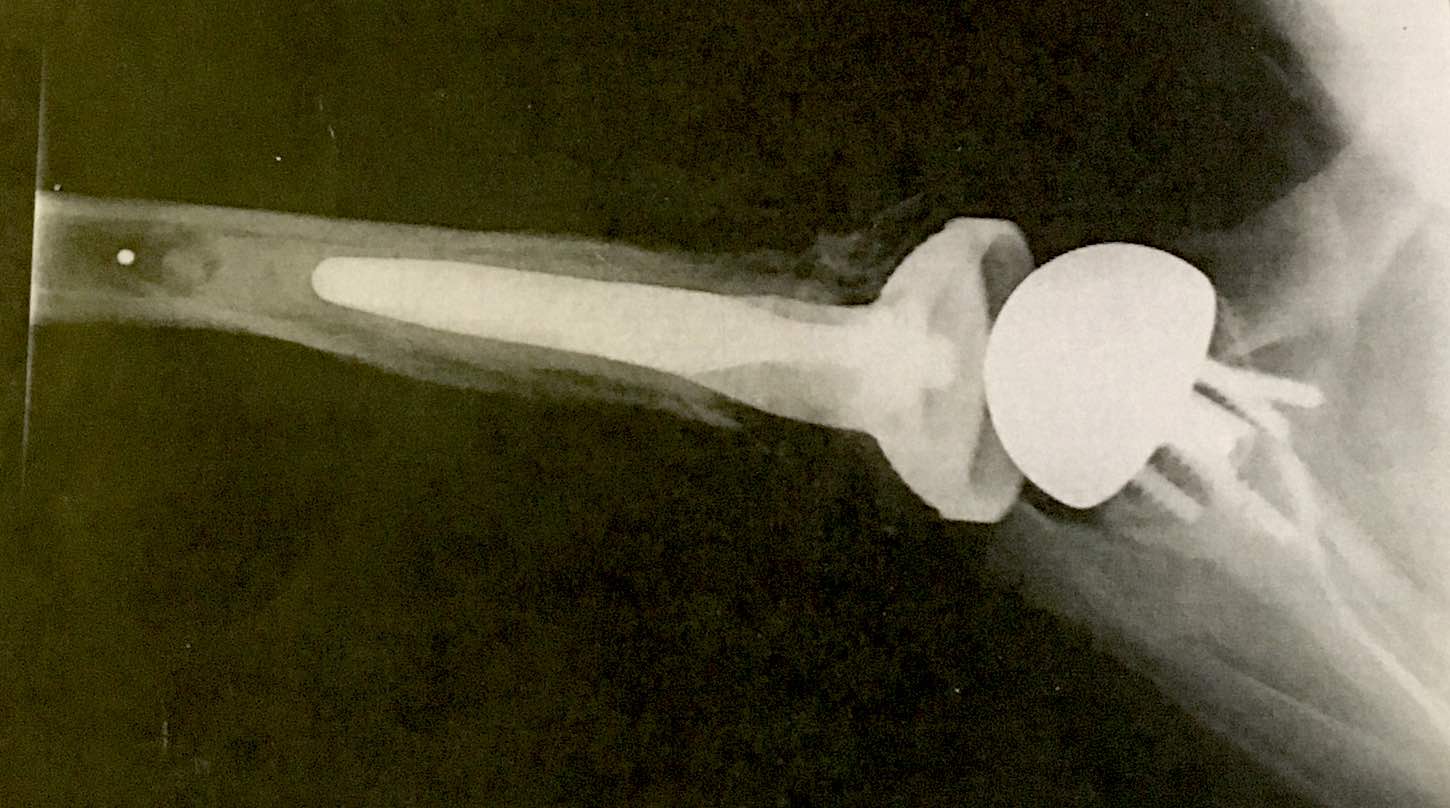

lo recuerdo. Me acuerdo de que el cirujano fue

a verme, pero es un recuerdo borroso. ¿Fue

entonces cuando me dijo que había usado el

índice y el pulgar para sacar la cabeza de mi

humero de la incisión con los restos de mi

brazo? No, me dijo eso más tarde yo creo.

Durante la rehabilitación (en la que usábamos

solamente español), siempre me decían cosas

como:

—Quiero que levantes la pierna diez veces.

¡Cuéntalas!

No podía. Literalmente no podía contar de uno

a diez por una semana y media.

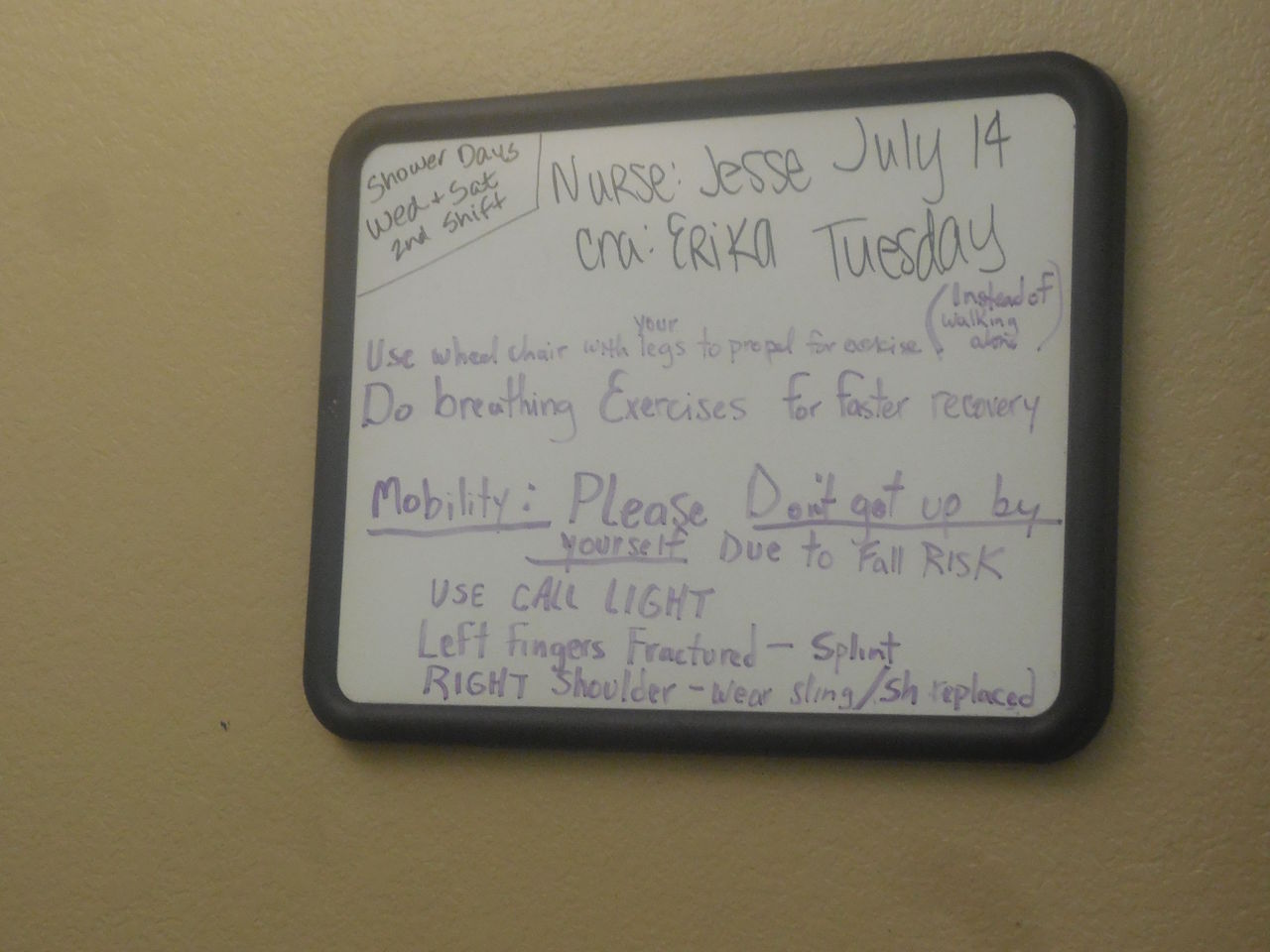

Por dos semanas yo estuve internado en una

facilidad de enfermería. Se negaban a dejarme

ir a casa porque vivo solo y las enfermeras no

querían que me cayera.

Cuando por fin había regresado a casa, unas

enfermeras iban todos los días para darme

terapia. No podía mover el brazo ni siquiera

un centímetro y no podía levantar el brazo.

Una enfermera me levantó el brazo hacia

arriba. El brazo había estado atrapado en el

cabestrillo por mucho tiempo y anhelaba

zafarse de él y estirarse.

—¡Oh! ¡Se está muy a gusto! —le dije.

Ella me enseñó a usar la mano izquierda para

levantar el brazo herido.

El día en él que regresé a casa compré un

ukelele.

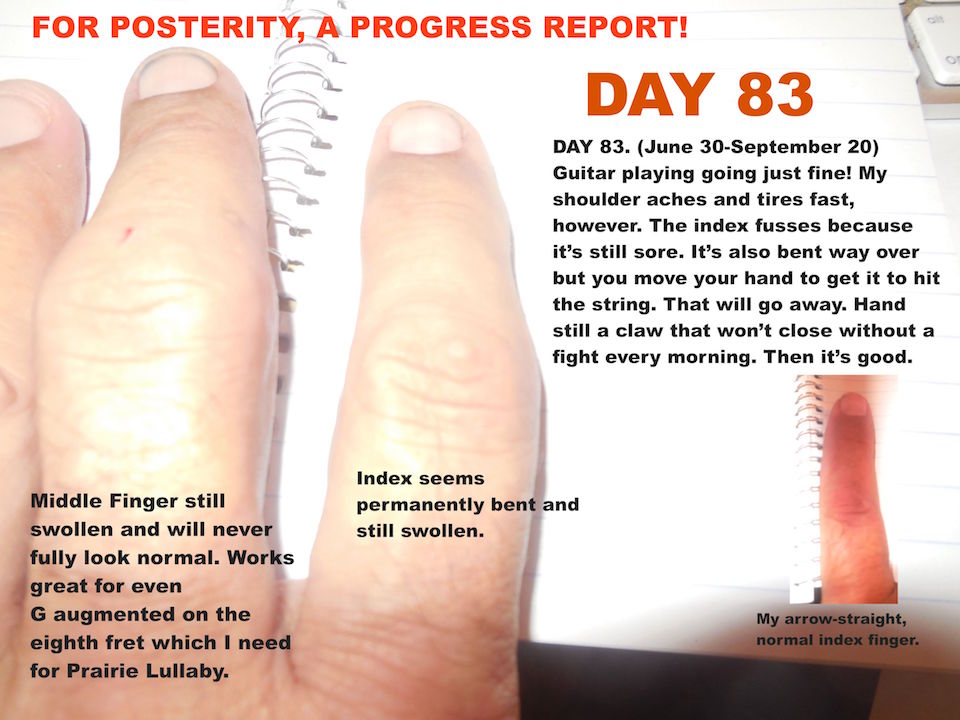

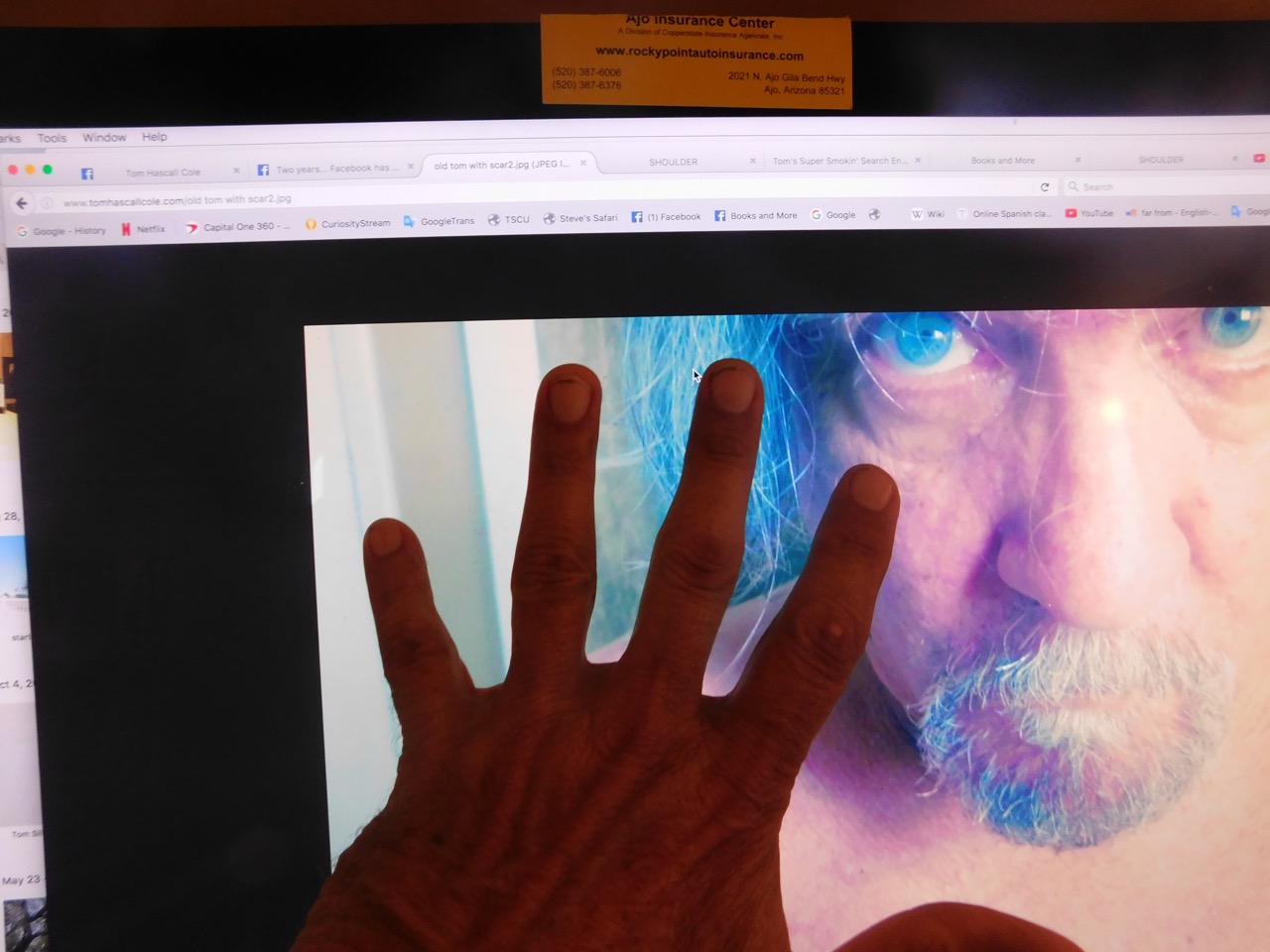

El especialista de manos estaba de

acuerdo conmigo que sería buena idea empezar a

tocarlo en vez de una guitarra. Al principio,

ni siquiera podía cerrar la mano, pero con

mucha terapia empezaba a mejorarse y al fin

recobré el uso de la mano e incluso toqué en

el bar que me había contratado meses antes.

El especialista de manos estaba de

acuerdo conmigo que sería buena idea empezar a

tocarlo en vez de una guitarra. Al principio,

ni siquiera podía cerrar la mano, pero con

mucha terapia empezaba a mejorarse y al fin

recobré el uso de la mano e incluso toqué en

el bar que me había contratado meses antes.

Había otra cosa pendiente, pero tenía que

sacudirme las telas de araña un poquito antes

de llevarla a cabo. Me refiero a la cita que

tenía con un cierto anestesista. Por fin se me

había recuperado el cerebro y podía escribir

mi queja al hospital y al anestesista. No

anduve con rodeos.

Envié al cirujano una carta avisándole lo que

estaba pasando antes de sus cirugías: que el

anestesista acechaba para dar proselitismo a

los pacientes. En el mismo sobre envié la

carta que había escrito al anestesista y media

docena de los superiores del anestesista

también iban a recibir copias incluyendo el

jefe de los tres hospitales del área, Tim

Bricker.

August 17, 2015

Dr. Scott Siebel

Chandler Anesthesia Consultants

PO Box 1847

Gilbert, AZ 85299

Querido Dr. Siebel:

Su práctica de pedir que pacientes participen

en actividades religiosas es poco ética. Digo

esto suponiendo que no soy el único al que ha

tratado de hacer orar con usted.

No tenía ningún derecho de pedir que yo me

uniera con usted para orar justo minutos antes

de mi cirugía mayor. No sabe nada de mis

creencias religiosas y no soy un miembro de su

iglesia.

Conozco a muy poca gente que quisiera

arrodillarse y orar con usted, un completo

desconocido.

Sí, estoy seguro que ha habido otros pacientes

que con mala gana y descontento han consentido

sus raras e inquietantes peticiones sabiendo

que al poco tiempo usted tendría las vidas en

sus manos. Ha podido hacer eso solamente por

la situación intimidante de la que Ud. como

anestesista se puede aprovechar.

Yo estaba en el hospital para tener los

servicios del Dr. Paterson y su anestesista no

para ser su compañero de rezos.

Me negué a orar con usted aunque supiera que

tendría un anestesista que estaba picado por

mi represión y decepcionado por ser privado de

su oración prequirúrgica de costumbre. Tal

doctor podría estar un poquito despistado y

por supuesto no quería esto. Solo por esa

razón claramente era poco ético de usted de

haberme metido en esta situación.

Mercy Gilbert Hospital y Chandler Anesthesia

Consultants, sin querer, me han fallado.

Dr. Siebel, sus superiores necesitan saber que

está aprovechándose de personas enfermas y

dañadas (pacientes de cuyas afiliaciones

religiosas usted no sabe absolutamente nada)

por intentar de imponer sus propias prácticas

religiosas sobre ellos.

Esta clase de comportamiento, este

proselitismo deliberado claramente no se

acepta en ninguna parte.

No quiero tener una respuesta suya. Sin

embargo, quisiera tener respuestas de sus

superiores, en el Mercy Gilbert Hospital,

Chandler Regional Medical Center y Chandler

Anesthesia Consultants.

Me gustaría saber que a otros no se les pedirá

que participen en las actividades religiosas

de su anestesista como yo y que se tomarán

medidas correctivas y disciplinarias

apropiadas para asegurar que tales prácticas

poco éticas y egoístas cesen.

Atentamente,

Tom Cole

En vísperas de septiembre recibí una carta de

su jefe.

Querido Sr. Cole:

He recibido y leído su queja respecto al Dr.

Scott Siebel.

Habiendo conocido al Dr. Siebel por muchos

años, estoy seguro que él no tiene la

intención de hacer mal a nadie. Sin embargo,

él ha sido informado de su descontento y ahora

sabe que no todos derivan consuelo de oración.

Me ha asegurado que esta práctica cesará

inmediatamente.

Quisiera darle las gracias por informarme de

esto.

Terry Ambus MD

Bueno, no podría haber esperado nada mejor. Me

gustaba la palabra "inmediatamente".

Por otra parte, aunque entendía que Dr. Ambus

tenía que defender a su empleado un poquito y

decir que no tenía malas intenciones, no me

gustaba la idea de que el anestesista fuera un

inocentón que no sabía lo que estaba haciendo.

No merecía tal pase. Scott Siebel nunca habría

tratado de orar con un paciente si el cirujano

hubiera estado allí. Habría sido pillado

instantáneamente y él bien lo sabía. El modus

operandi de tales mojigatos es quedarse a

solas con el paciente. Esto es lo que hizo

aquel pastor con mi madre hace años.

Personas de ese pelaje no son tan estúpidas e

ingenuas como nos gusta creer. Mejor dicho, no

son tan estúpidas e ingenuas como ellas mismas

quieren que creamos.

Más vale que el Sr. Siebel sea retratado como

un ingenuo que como el predador que es: un

predador de poca monta tal vez, pero no

obstante un predador.

Escribí corriendo esta carta:

Querido Dr. Ambus:

Nada más una nota para darle las gracias por

su carta. Creo que entendía mi preocupación.

Creo también que se enteró de que yo no había

hecho mi queja a la ligera.

Quisiera decirle que agradezco mucho su

oportuna y apropiada respuesta.

Tom Cole

No todo iba a marchar sobre rieles. Recibí

una respuesta del hospital Mercy

Gilbert. Vino en forma de una simplona carta

de desprecio escrita por un idiota de primera

llamado Philip Fracica. Me puso furioso y

redacté una carta de cinco páginas

destripándole a él y al hospital por haber

contratado a tal retrasado. La consideraba mi

obra maestra entre todas las cartas que había

escrito en la vida y con un gran orgullo la

envié a todas las partes involucradas.

A loathsome man named Fracica

Was known from Maine to Topeka

As an oblivious pulmonologist

A litigious ideologist

And a prodigious religious apologist!

Acusé al hospital de no tener la menor idea de

lo que constaba una política de quejas y para

gran sorpresa mía un día descubrí que al

recibir mi carta el hospital abandonó esa

llamada política completamente: el jefe de los

tres hospitales, Tim Bricker me llamó para

pedir perdón.

Dijo que estaba totalmente de acuerdo conmigo

con cada cosa que había escrito (y yo había

escrito muchas). Me dijo que era un judío a

quien no le gustaba ningún proselitismo e

incluso había llamado a Terry Ambus para

decírselo.

No creo que me estuviera haciendo la pelota

para nada. Hablamos por media hora muchas

veces riéndonos.

Después, algo muy raro e interesante sucedió.

Resultó que había un par de cosas que quisiera

haberle dicho a Tim Bricker. No sé por qué

pero esto me molestaba mucho y empecé a

imaginarme que me hubiera topado con él en

algún restaurante o bar y así tuviera la

oportunidad de hablarle otra vez. Había visto

su foto en la página web del hospital y por

eso sabía que podría reconocerlo. Era una de

esas imaginaciones que supongo que todo el

mundo tiene de vez en cuando.

Un día me decidí a tomar una cerveza en una

cervecería pequeña que se llama La Percha por

sus muchas jaulas llenas de pájaros exóticos.

Yo había actuado allí muchas veces.

Yo estaba gozando de una cerveza de la India

cuando vi a un hombre chaparro vestido de

vaqueros y una camiseta. Le pregunté:

—Es usted Tim Bricker?

—Eso depende de quién lo quiere saber — dijo

sonriendo.

Fue él. Estaba esperando a su esposa así que

charlamos un rato.

Al terminar mi cerveza me levanté

para irme y pasé por la mesa donde ellos

estaban sentados. Él me señaló y me presentó a

su esposa.

—Su esposo leyó cinco páginas de mi

sermón más fino —le dije.

Tim Bricker le miró a su esposa y

asintió con la cabeza.

—Fue un buen sermón —dijo. |

19. The Fall

As a

general rule, people aren't able to remember

much of what happened to them before the age

of five. Just the same, I remember quite well

what happened to me one day when I must have

been four or so. I fell out of a shopping cart

and hit my head against the hard floor of a

grocery store named Weiss's Market.

I don't

remember the fall, nor the trip to the

hospital. I do, however, remember the dream I

had when I was unconscious. There were two

lines of men and women dressed in white coats.

Those in one of the lines held my hands and

those in the other my feet, and they threw me

to one another through a long hallway until,

at last, I arrived in the doctor's office

where he rubbed a green powder on my knee.

How strange, I

said to myself, that he put the powder on my

knee knowing full well that that accident had

injured my head.

I regained

consciousness, and the doctor gave me a

flashlight and taught me how to turn it on and

off.

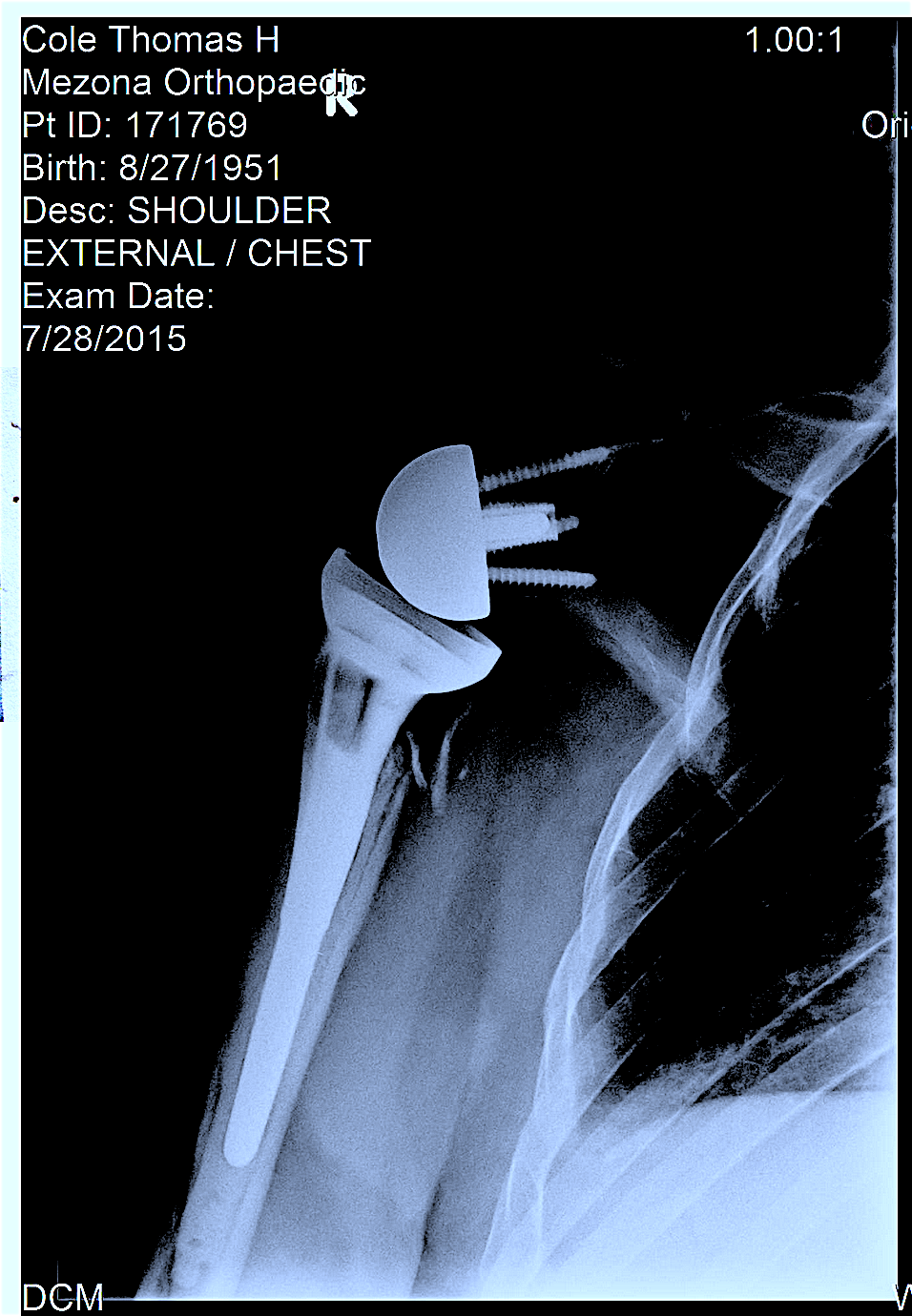

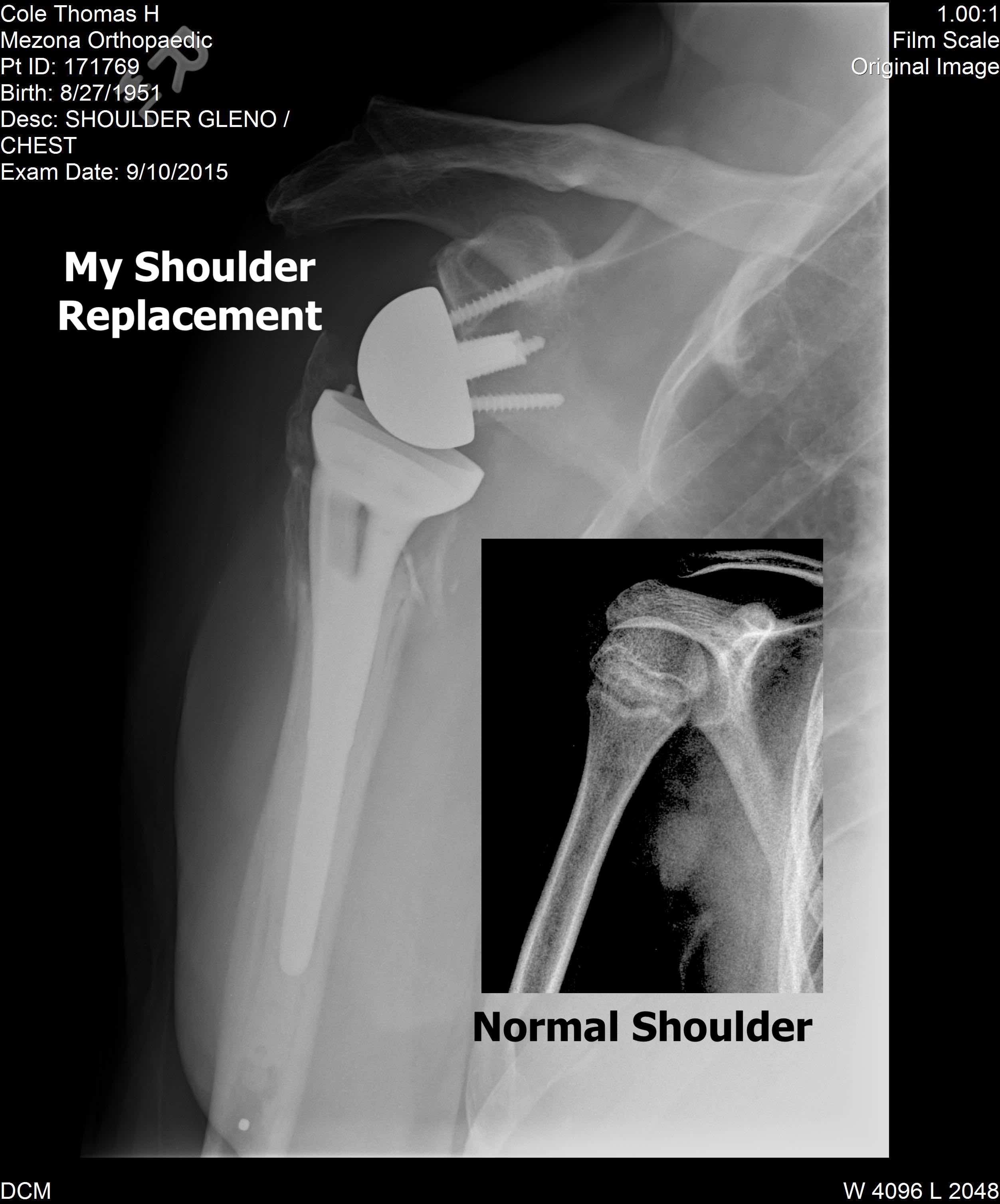

MY CYBORG SHOULDER

In June of 2015 I auditioned for a gig in

a bar some four blocks from where I live. I

played the guitar and sang for two hours and

it seemed that they liked me because

afterwards they hired me to play during the

afternoon of the fourth of July when they were

having a special party.

I wouldn't be able to make it.

Upon arriving home, I put my sound equipment

in the kitchen. I didn't feel like putting it

away because a year and a half before I had

fallen off my bicycle and hurt my shoulder. It

still hurt a little. I had had therapy, but

they weren't able to help me and finally I had

to have a cat scan.

The procedure turned out to be incredibly

painful. I knew that they were going to stick

me in a white, porcelain-like cylinder and I

had heard that patients frequently had a

terrible sensation of claustrophobia when put

inside. I didn't think this this would happen

to me. I was wrong.

It was like being loaded head first into a

cannon!

The technician showed me that the two ends of

the cylinder were open and when I knew that, I

was able to relax a little.

Of course, the claustrophobia wasn't painful.

It was something else. If I didn't move my

arm, it would begin to hurt and during the

procedure the technician didn't allow me to

move at all.

The pain grew.

There was a speaker in the cylinder and when

the technician asked me how I was, I answered,

"I'm dying!"

"You've only got ten minutes left. Don't

move."

I thought I was going to die.

Afterwards, the doctor showed me the results

that were on a screen although I must confess

that I couldn't understand what I was looking

at. She told me that I had torn off a tendon

and that it was beyond the ability of any

surgeon to repair it.

"The good news is that you can keep riding

your bike because if you ever fall off it

again you won't be able to hurt your shoulder

any more than it already is.

"Isn't there anything you can do?" I asked.

"Well, you could have a complete shoulder

replacement."

I thought that she was talking about a

replacement using the bones of a cadaver and I

didn't want to have anything to do with that.

"There's something else," she said. "You have

torn off two tendons, but one appears to be an

old injury and the muscles around it are

atrophied.

I couldn't remember having hurt my shoulder

before.

My shoulder hurt a lot but I could still play

guitar at a bar Wednesdays and when a year had

gone by, my shoulder stopped hurting as much

as before.

On that day in June, I looked at the equipment

in the kitchen. I had left some big speakers,

the sound system amplifier, and other things

in the central part of the room through which

I was used to walking and I said to myself,

"Tom, you're gonna trip over that."

That night at 11:20, I turned out the lights,

walked through the kitchen, tripped over my

sound system, and broke two fingers and my

shoulder.

At the time I didn't know that I had broken my

shoulder. It hurt, but it always did. What

concerned me most were the fingers, one of

which had been dislocated and was pointing to

the left. It was absolutely ghastly.

I called my brother and he told me to call

911. I did and the firemen rushed to my house.

They arrived with their hook and ladder truck

and their ambulance, which I always used to

call "The Sun Lakes Taxi."

The firemen seemed a little bored with it all.

It surprised me a lot that they didn't talk to

me much and didn't offer words of

encouragement. In the past, I had always been

quite impressed to see the professionalism of

other firemen and the way that they reassured

injured people.

"Do you have pain anywhere else?" a fireman

asked, looking at my hand.

"Well," I answered. "My shoulder hurts a

little."

They took me to the hospital where they cut

off my favorite T-shirt with scissors and the

doctor asked me, "Do I have your permission to

set your finger?"

I nodded and she said that I had to answer her

in words.

"Why?" I asked.

"Sometimes they break."

"All right, then," I told her. "You've got my

permission."

She came up, grabbed my finger, and started

yanking.

And I started screaming.

My brother told me that I woke up every

patient on that floor of the hospital.

"She had guts!" my brother told me later.

The finger didn't break.

Usually when a person breaks a bone, the

doctor can set it and send the patient home

with their arm or leg in a cast. It wouldn't

be that way for me.

They had a piece of equipment like an MRI

machine. (I don't know exactly what it was.)

And they scanned my body with it.

"They say you've broken your shoulder," my

brother told me. "It's bad and you have to

have a replacement."

They put my hand in a splint and my arm in a

sling and sent me home that very night. I had

to wait ten days before the surgery. In the

meantime, I went to see a hand specialist, a

doctor that told me, "These fingers are going

to give you more trouble than the whole

shoulder."

He warned me that I had an injury that

typically resulted in stiffness in the hand

and that quite possibly I would not be able to

play the guitar again.

My brother talked to the orthopedic surgeon

who gave him instructions that I had to follow

before the surgery. He wrote: "1. no

medication that morning 2. no deodorant..."

I arrived at the hospital well prepared on the

day of the surgery. Before the operation, I

was in a bed and my brother was in the room

too. The anesthesiologist explained to me what

was going to happen. Then he said, "Let's say

a short prayer."

We both became furious instantly and yelled at

the same time.

"No!!"

In that moment, the anesthesiologist realized

that his selfish attempt to deceive and

manipulate had failed. He had been caught and

he knew it.

That's the last thing I remember.

What I write in my book, The Mysterious Nights

of Yesteryear, illustrates the reason why we

got so mad. It has to do with what happened

when my mom was dying of cancer.

A pastor from where I don't know showed up. He

was like the other buzzards of his kind that

always come to roost in the trees when

somebody's sick...Out of courtesy, my mother

said that he could talk to her...

I talked to my mother, who told me that she

had told this pastor that she wasn't a

Christian, but he didn't care. She was very

weak and this cleric knew that he could take

advantage of her. He took her hand and began

to pray to Jesus Christ.

I went looking for him, and I aimed to kill

him very slowly with my bare hands.

Fortunately for this religious swine, he had

left, getting away Scott free.

I didn't want my mother to spend her last day

on earth being the victim of such a predator

and upon awakening after the operation I was

bound and determined that this

anesthesiologist would never escape my wrath.

But I took a long time waking up. Perhaps this

anesthesiologist had given me a double dose of

anesthesia so I wouldn't remember what he

tried to pull.

I dreamed about a nurse. She was a brunette,

female version of Brainiac V that was sitting

on a whirling chair in front of a screen that

sparked and glittered. I felt pain, but since

she was reading my mind, she already knew

before I could tell her about it and said she

had already sent the pain killers on the way.

The blue of her eyes splashed across the

screen. Hours crawled by.

I had thought that someone would see me wake

and say, "You've already had your operation."

as they do when someone has had sodium

pentothal and hasn't had any sense of the

passing of time. I thought I would have a

sudden awakening.

They told me that my nephew visited me, but I

don't remember that. I remember that the

surgeon came to see me, but it's a blurry

recollection. Was it then that he told me that

he had used his thumb and index finger to lift

out the head of my humerus along with the

remains of my arm? No, he said that later I

think.

During rehab (in which we used only Spanish),

they always said things like, "I want you to

lift your leg ten times. Count them off!"

But I couldn't. I literally could not count

from one to ten for a week and a half.

For two weeks I was stuck in a rehabilitation

facility. They refused to let me go home

because I live alone and the nurses didn't

want me to fall.When I had at last gone home,

nurses came every day to give me therapy. I

couldn't move my arm a single inch and I

couldn't lift my arm.

A nurse lifted my arm up for me. The arm had

been trapped in the sling for a long time, and

it longed to be free and to stretch.

"Oh, that feels great!" I told her.

She showed me how to use my left hand to lift

my injured arm.

The very day I went home I bought a ukulele.

The hand specialist agreed with me that it

would be a good idea to start playing it

instead of a guitar. At first, I couldn't even

close my hand, but with a lot of therapy it

began to get better and finally I recovered

the use of my hand and even played in the bar

that had hired me months before.There was

something else pending that I couldn't carry

out until I had shaken the cobwebs from my

mind. I'm talking about the date that I had

with a certain anesthesiologist. At last my

cerebrum recuperated and I was able to compose

my complaint to the hospital and the

anesthesiologist. I didn't beat around the

bush.

The hand specialist agreed with me that it

would be a good idea to start playing it

instead of a guitar. At first, I couldn't even

close my hand, but with a lot of therapy it

began to get better and finally I recovered

the use of my hand and even played in the bar

that had hired me months before.There was

something else pending that I couldn't carry

out until I had shaken the cobwebs from my

mind. I'm talking about the date that I had

with a certain anesthesiologist. At last my

cerebrum recuperated and I was able to compose

my complaint to the hospital and the

anesthesiologist. I didn't beat around the

bush.

I mailed the surgeon a letter advising him of

what was going on just before surgery: that

his anesthesiologist was lying in wait to

proselytize with the patients. In the same

envelope, I enclosed the letter that I had

written to the anesthesiologist and a half

dozen of his superiors were also to receive

copies, including the president and CEO of the

three hospitals in the area, Tim Bricker.

August 17, 2015

Dr. Scott Siebel

Chandler Anesthesia Consultants

Re: ACCT #C14.41813 and Surgery

July 10, 2015 at Mercy Gilbert Hospital

PO Box 1847

Gilbert, AZ 85299

Dear Dr. Siebel:

Your practice of asking patients to

participate in religious activity is

unethical. I say this assuming that I'm not

the only one you have attempted to get to pray

with you.You had no right to ask me to join

you in "a short prayer" just minutes before my

major surgery. You know nothing of my

religious affiliation and I am not a member of

your church.

I know precious few people who would want to

bow down and pray with you, a total stranger.

Yes, I'm sure some of your patients may

reluctantly and unhappily acquiesce to your

strange and unsettling prayer requests knowing

that in only minutes you will literally have

their lives in your hands. But their

acquiescence is due only to the clear

coerciveness of the situation which you as an

anesthesiologist can take advantage of.

I was there as a patient to receive services

from a surgeon, Dr. William Paterson, and his

anesthesiologist--not to be your prayer

partner.

I refused to pray with you even though I

risked having an anesthesiologist that was

miffed by my rebuke or crestfallen at being

denied his customary pre-surgery prayer. Such

a doctor might be just a little off his game

and I certainly didn't want that. For that

reason alone, it was clearly unethical of you

to put me in that position.

Mercy Gilbert and Chandler Anesthesia

Consultants I feel have inadvertently let me

down.Dr. Siebel, your superiors need to know

that you are taking advantage of sick and

injured patients (whose religious affiliations

you know absolutely nothing about) by

attempting to impose your own personal

devotional practices upon them. Such conduct,

such willful proselytizing, is simply

unacceptable anywhere.

I do not wish to have a reply from you. I do,

however, wish to hear from your employers,

Mercy Gilbert Hospital, Chandler Regional

Medical Center, and Chandler Anesthesia

Consultants. I would like to know that others

will not be asked to participate in their

anesthesiologist's religious activities as I

was and that proper remedial and disciplinary

measures will be taken to ensure that such

unethical, self-serving practices will cease.

Sincerely,

Tom Cole

cc: William Paterson, Tim Bricker, Karen

Byrnes, Marcia Bolks, Terry Ambus, Arizona

Medical Board

In the beginning of September, I received a

letter from his boss.

Dear Mr. Cole:

I have received and read your complaint

regarding Dr. Scott Siebel.

Knowing Dr. Siebel for many years, I am sure

he does not intend malice towards anyone.

Nevertheless, your dissatisfaction has been

brought to his attention, and he now realizes

that not everyone is comforted by prayer prior

to surgery. He gave me assurance that this

practice will cease immediately.

I want to thank you for bringing this forward.

Terry Ambus MD

Well, I couldn't have expected anything

better. I liked the word "immediately."

On the other hand, although I understood that

Dr. Ambus had to defend his employee a little

and say that he didn't have bad intentions, I

didn't like the idea that the anesthesiologist

was an innocent who didn't understand what he

was doing. He didn't deserve that pass. Scott

Siebel would never have tried to pray with a

patient if the surgeon had been there. He

would have be caught at once and he knew that

very well. The modus operandi of such holy

rollers is to get the patient alone. That's

what that pastor did with my mother years ago.

People of this lowly sort are not as stupid

and naive as they would like us to believe.

For Scott Siebel, it's better to be scolded as

an naive child than as the predator that he

is: a penny ante predator perhaps but a

predator nonetheless.

I dashed off this letter.

Dear Dr. Ambus:

Just a note to thank you for your reply to my

letter. I feel that you understood my concern.

I also feel that you were aware of the fact

that I did not make this, my first such

complaint, lightly. I want you to know how

much I appreciate your timely and appropriate

response.

Tom Cole

Not everything was to go smoothly. I received

an answer from Mercy Gilbert Hospital. It came

in the form of a simplistic brush-off letter

written by an first class idiot named Philip

Fracica. I was furious and wrote a five-page

letter disemboweling him and the hospital as

well for hiring a such a simpleton. I

considered it my masterpiece among all of the

letters that I had written in my life and it

was with great pride that I mailed it to all

concerned.

A loathsome man named Fracica

Was known from Maine to Topeka

As an oblivious pulmonologist

A litigious ideologist

And a prodigious religious apologist!

I accused the hospital of not having the

slightest idea of what a grievance procedure

was and much to my surprise one day I found

that upon receiving my letter the hospital

abandoned this so-called grievance procedure

entirely: the CEO of the three hospitals Tim

Bricker called me to apologize.

He said that he was in

total agreement with me on each issue about

which I had written (and I had written quite

a lot). He told me that he was Jewish and

didn't like any kind of proselytizing and

had even called Terry Ambus to tell him so.

I don't think he was just

mollifying me at all. We talked for a half

hour laughing a lot of the time.

Afterwards, something quite strange and

interesting happened. It just so happened that

there were a couple of things that I wished I

had said to Tim Bricker. I don't know why but

this bothered me a lot and I began to imagine

having run into him at a restaurant or bar and

that I had the opportunity to talk to him

again. I had seen his picture on the

hospital's web page and so I knew I could

recognize him. It was just one of those

imaginings that I suppose all of us have from

time to time.

One day, I decided to have a beer at a brewery

called The Perch because of its manybird cages

filled with exotic birds. I had played guitar

there many times.

I was having an India pale ale when I spotted

a short man dressed in blue jeans and a

T-shirt.

"Are you Tim Bricker?" I asked him.

"That depends on who wants to know," he said

smiling.

It was him. He was waiting for his wife

and so we chatted for a while.

After I finished my beer, I got up to

go and walked by the table where they were

sitting. He waved me over and introduced me to

his wife.

"Your husband read five pages of my

finest rant," I told her.

Tim Bricker looked at his wife and nodded.

"It was a good rant," he said.

|

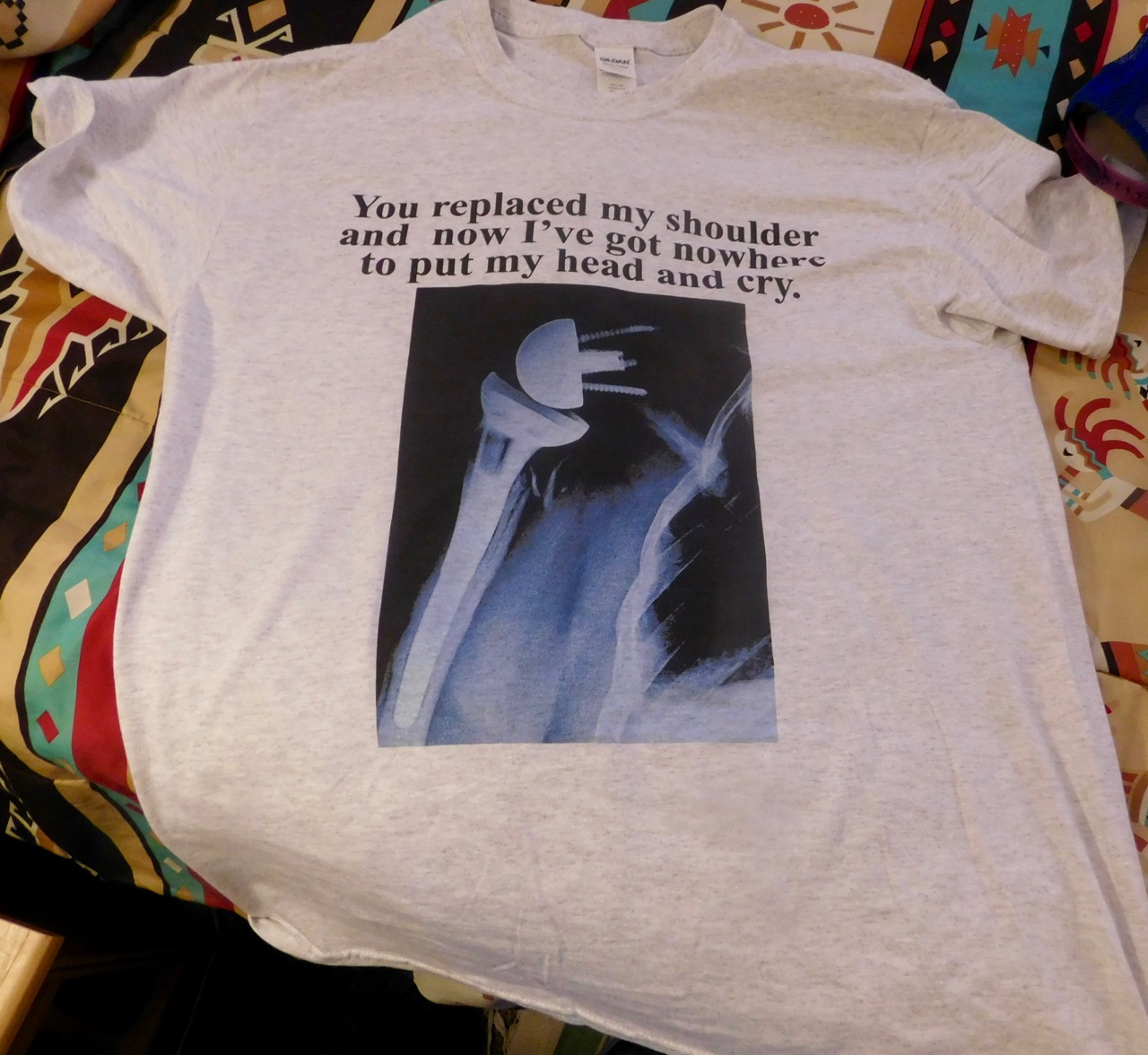

"You

Replaced My Shoulder and Now I've Got Nowhere to

Put My Head and Cry."

"You

Replaced My Shoulder and Now I've Got Nowhere to

Put My Head and Cry."

"You

Replaced My Shoulder and Now I've Got Nowhere to

Put My Head and Cry."

"You

Replaced My Shoulder and Now I've Got Nowhere to

Put My Head and Cry."