I met him first in a

hurricane; and though we had gone through the

hurricane on the same schooner, it was not until the

schooner had gone to pieces under us that I first

laid eyes on him. Without doubt I had seen him with

the rest of the kanaka crew on board, but I had not

consciously been aware of his existence, for the

Petite Jeanne was rather overcrowded. In addition to

her eight or ten kanaka seamen, her white captain,

mate, and supercargo, and her six cabin passengers,

she sailed from Rangiroa with something like

eighty-five deck passengers-- Paumotans and

Tahitians, men, women, and children each with a

trade box, to say nothing of sleeping mats,

blankets, and clothes bundles.

The pearling season in the Paumotus

was over, and all hands were returning to Tahiti.

The six of us cabin passengers were pearl buyers.

Two were Americans, one was Ah Choon (the whitest

Chinese I have ever known), one was a German, one

was a Polish Jew, and I completed the half dozen.

It had been a prosperous season. Not

one of us had cause for complaint, nor one of the

eighty-five deck passengers either. All had done

well, and all were looking forward to a rest-off and

a good time in Papeete.

Of course, the Petite Jeanne was

overloaded. She was only seventy tons, and she had

no right to carry a tithe of the mob she had on

board. Beneath her hatches she was crammed and

jammed with pearl shell and copra. Even the trade

room was packed full with shell. It was a miracle

that the sailors could work her. There was no moving

about the decks. They simply climbed back and forth

along the rails.

In the night time they walked upon

the sleepers, who carpeted the deck, I'll swear, two

deep. Oh! And there were pigs and chickens on deck,

and sacks of yams, while every conceivable place was

festooned with strings of drinking cocoanuts and

bunches of bananas. On both sides, between the fore

and main shrouds, guys had been stretched, just low

enough for the foreboom to swing clear; and from

each of these guys at least fifty bunches of bananas

were suspended.

It promised to be a messy passage,

even if we did make it in the two or three days that

would have been required if the southeast trades had

been blowing fresh. But they weren't blowing fresh.

After the first five hours the trade died away in a

dozen or so gasping fans. The calm continued all

that night and the next day--one of those glaring,

glassy, calms, when the very thought of opening

one's eyes to look at it is sufficient to cause a

headache.

The second day a man died--an Easter

Islander, one of the best divers that season in the

lagoon. Smallpox--that is what it was; though how

smallpox could come on board, when there had been no

known cases ashore when we left Rangiroa, is beyond

me. There it was, though--smallpox, a man dead, and

three others down on their backs.

There was nothing to be done. We

could not segregate the sick, nor could we care for

them. We were packed like sardines. There was

nothing to do but rot and die--that is, there was

nothing to do after the night that followed the

first death. On that night, the mate, the

supercargo, the Polish Jew, and four native divers

sneaked away in the large whale boat. They were

never heard of again. In the morning the captain

promptly scuttled the remaining boats, and there we

were.

That day there were two deaths; the

following day three; then it jumped to eight. It was

curious to see how we took it. The natives, for

instance, fell into a condition of dumb, stolid

fear. The captain--Oudouse, his name was, a

Frenchman--became very nervous and voluble. He

actually got the twitches. He was a large fleshy

man, weighing at least two hundred pounds, and he

quickly became a faithful representation of a

quivering jelly-mountain of fat.

The German, the two Americans, and

myself bought up all the Scotch whiskey, and

proceeded to stay drunk. The theory was

beautiful--namely, if we kept ourselves soaked in

alcohol, every smallpox germ that came into contact

with us would immediately be scorched to a cinder.

And the theory worked, though I must confess that

neither Captain Oudouse nor Ah Choon were attacked

by the disease either. The Frenchman did not drink

at all, while Ah Choon restricted himself to one

drink daily.

It was a pretty time. The sun, going

into northern declination, was straight overhead.

There was no wind, except for frequent squalls,

which blew fiercely for from five minutes to half an

hour, and wound up by deluging us with rain. After

each squall, the awful sun would come out, drawing

clouds of steam from the soaked decks.

The steam was not nice. It was the

vapor of death, freighted with millions and millions

of germs. We always took another drink when we saw

it going up from the dead and dying, and usually we

took two or three more drinks, mixing them

exceptionally stiff. Also, we made it a rule to take

an additional several each time they hove the dead

over to the sharks that swarmed about us.

We had a week of it, and then the

whiskey gave out. It is just as well, or I shouldn't

be alive now. It took a sober man to pull through

what followed, as you will agree when I mention the

little fact that only two men did pull through. The

other man was the heathen--at least, that was what I

heard Captain Oudouse call him at the moment I first

became aware of the heathen's existence. But to come

back.

It was at the end of the week, with

the whiskey gone, and the pearl buyers sober, that I

happened to glance at the barometer that hung in the

cabin companionway. Its normal register in the

Paumotus was 29.90, and it was quite customary to

see it vacillate between 29.85 and 30.00, or even

30.05; but to see it as I saw it, down to 29.62, was

sufficient to sober the most drunken pearl buyer

that ever incinerated smallpox microbes in Scotch

whiskey.

I called Captain Oudouse's attention

to it, only to be informed that he had watched it

going down for several hours. There was little to

do, but that little he did very well, considering

the circumstances. He took off the light sails,

shortened right down to storm canvas, spread life

lines, and waited for the wind. His mistake lay in

what he did after the wind came. He hove to on the

port tack, which was the right thing to do south of

the Equator, if--and there was the rub--if one were

not in the direct path of the hurricane.

We were in the direct path. I could

see that by the steady increase of the wind and the

equally steady fall of the barometer. I wanted him

to turn and run with the wind on the port quarter

until the barometer ceased falling, and then to

heave to. We argued till he was reduced to hysteria,

but budge he would not. The worst of it was that I

could not get the rest of the pearl buyers to back

me up. Who was I, anyway, to know more about the sea

and its ways than a properly qualified captain? was

what was in their minds, I knew.

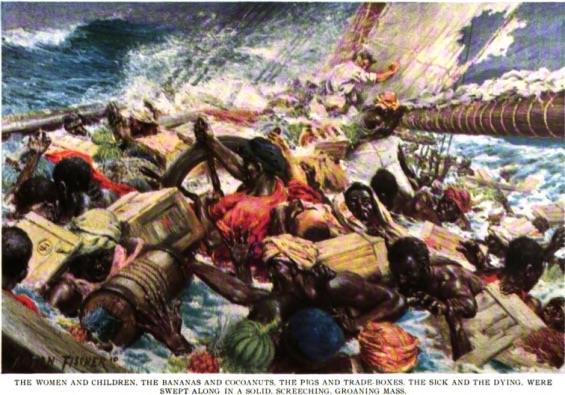

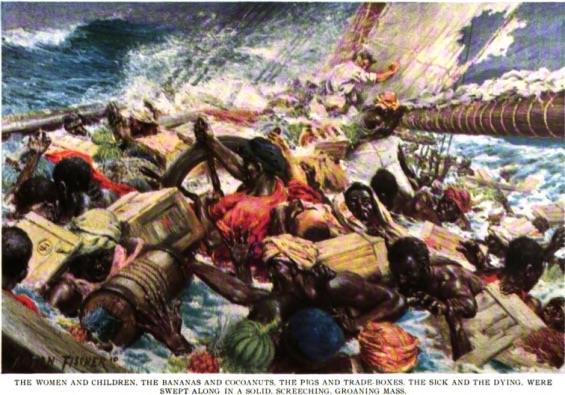

Of course, the sea rose with the wind

frightfully; and I shall never forget the first

three seas the Petite Jeanne shipped. She had fallen

off, as vessels do at times when hove to, and the

first sea made a clean breach. The life lines were

only for the strong and well, and little good were

they even for them when the women and children, the

bananas and cocoanuts, the pigs and trade boxes, the

sick and the dying, were swept along in a solid,

screeching, groaning mass.

The second sea filled the Petite

Jeanne'S decks flush with the rails; and, as her

stern sank down and her bow tossed skyward, all the

miserable dunnage of life and luggage poured aft. It

was a human torrent. They came head first, feet

first, sidewise, rolling over and over, twisting,

squirming, writhing, and crumpling up. Now and again

one caught a grip on a stanchion or a rope; but the

weight of the bodies behind tore such grips loose.

One man I noticed fetch up, head on

and square on, with the starboard bitt. His head

cracked like an egg. I saw what was coming, sprang

on top of the cabin, and from there into the

mainsail itself. Ah Choon and one of the Americans

tried to follow me, but I was one jump ahead of

them. The American was swept away and over the stern

like a piece of chaff. Ah Choon caught a spoke of

the wheel, and swung in behind it. But a strapping

Raratonga vahine (woman)--she must have weighed two

hundred and fifty--brought up against him, and got

an arm around his neck. He clutched the kanaka

steersman with his other hand; and just at that

moment the schooner flung down to starboard.

The rush of bodies and sea that was

coming along the port runway between the cabin and

the rail turned abruptly and poured to starboard.

Away they went--vahine, Ah Choon, and steersman; and

I swear I saw Ah Choon grin at me with philosophic

resignation as he cleared the rail and went under.

The third sea--the biggest of the

three--did not do so much damage. By the time it

arrived nearly everybody was in the rigging. On deck

perhaps a dozen gasping, half-drowned, and

half-stunned wretches were rolling about or

attempting to crawl into safety. They went by the

board, as did the wreckage of the two remaining

boats. The other pearl buyers and myself, between

seas, managed to get about fifteen women and

children into the cabin, and battened down. Little

good it did the poor creatures in the end.

Wind? Out of all my experience I

could not have believed it possible for the wind to

blow as it did. There is no describing it. How can

one describe a nightmare? It was the same way with

that wind. It tore the clothes off our bodies. I say

tore them off, and I mean it. I am not asking you to

believe it. I am merely telling something that I saw

and felt. There are times when I do not believe it

myself. I went through it, and that is enough. One

could not face that wind and live. It was a

monstrous thing, and the most monstrous thing about

it was that it increased and continued to increase.

Imagine countless millions and

billions of tons of sand. Imagine this sand tearing

along at ninety, a hundred, a hundred and twenty, or

any other number of miles per hour. Imagine,

further, this sand to be invisible, impalpable, yet

to retain all the weight and density of sand. Do all

this, and you may get a vague inkling of what that

wind was like.

Perhaps sand is not the right

comparison. Consider it mud, invisible, impalpable,

but heavy as mud. Nay, it goes beyond that. Consider

every molecule of air to be a mudbank in itself.

Then try to imagine the multitudinous impact of

mudbanks. No; it is beyond me. Language may be

adequate to express the ordinary conditions of life,

but it cannot possibly express any of the conditions

of so enormous a blast of wind. It would have been

better had I stuck by my original intention of not

attempting a description.

I will say this much: The sea, which

had risen at first, was beaten down by that wind.

'more: it seemed as if the whole ocean had been

sucked up in the maw of the hurricane, and hurled on

through that portion of space which previously had

been occupied by the air.

Of course, our canvas had gone long

before. But Captain Oudouse had on the Petite Jeanne

something I had never before seen on a South Sea

schooner--a sea anchor. It was a conical canvas bag,

the mouth of which was kept open by a huge loop of

iron. The sea anchor was bridled something like a

kite, so that it bit into the water as a kite bites

into the air, but with a difference. The sea anchor

remained just under the surface of the ocean in a

perpendicular position. A long line, in turn,

connected it with the schooner. As a result, the

Petite Jeanne rode bow on to the wind and to what

sea there was.

The situation really would have been

favorable had we not been in the path of the storm.

True, the wind itself tore our canvas out of the

gaskets, jerked out our topmasts, and made a raffle

of our running gear, but still we would have come

through nicely had we not been square in front of

the advancing storm center. That was what fixed us.

I was in a state of stunned, numbed, paralyzed

collapse from enduring the impact of the wind, and I

think I was just about ready to give up and die when

the center smote us. The blow we received was an

absolute lull. There was not a breath of air. The

effect on one was sickening.

Remember that for hours we had been

at terrific muscular tension, withstanding the awful

pressure of that wind. And then, suddenly, the

pressure was removed. I know that I felt as though I

was about to expand, to fly apart in all directions.

It seemed as if every atom composing my body was

repelling every other atom and was on the verge of

rushing off irresistibly into space. But that lasted

only for a moment. Destruction was upon us.

In the absence of the wind and

pressure the sea rose. It jumped, it leaped, it

soared straight toward the clouds. Remember, from

every point of the compass that inconceivable wind

was blowing in toward the center of calm. The result

was that the seas sprang up from every point of the

compass. There was no wind to check them. They

popped up like corks released from the bottom of a

pail of water. There was no system to them, no

stability. They were hollow, maniacal seas. They

were eighty feet high at the least. They were not

seas at all. They resembled no sea a man had ever

seen.

They were splashes, monstrous

splashes--that is all. Splashes that were eighty

feet high. Eighty! They were more than eighty. They

went over our mastheads. They were spouts,

explosions. They were drunken. They fell anywhere,

anyhow. They jostled one another; they collided.

They rushed together and collapsed upon one another,

or fell apart like a thousand waterfalls all at

once. It was no ocean any man had ever dreamed of,

that hurricane center. It was confusion thrice

confounded. It was anarchy. It was a hell pit of sea

water gone mad.

The Heathen Jack London

art b.jpg

The Petite Jeanne? I don't know. The

heathen told me afterwards that he did not know. She

was literally torn apart, ripped wide open, beaten

into a pulp, smashed into kindling wood,

annihilated. When I came to I was in the water,

swimming automatically, though I was about

two-thirds drowned. How I got there I had no

recollection. I remembered seeing the Petite Jeanne

fly to pieces at what must have been the instant

that my own consciousness was buffeted out of me.

But there I was, with nothing to do but make the

best of it, and in that best there was little

promise. The wind was blowing again, the sea was

much smaller and more regular, and I knew that I had

passed through the center. Fortunately, there were

no sharks about. The hurricane had dissipated the

ravenous horde that had surrounded the death ship

and fed off the dead.

It was about midday when the Petite

Jeanne went to pieces, and it must have been two

hours afterwards when I picked up with one of her

hatch covers. Thick rain was driving at the time;

and it was the merest chance that flung me and the

hatch cover together. A short length of line was

trailing from the rope handle; and I knew that I was

good for a day, at least, if the sharks did not

return. Three hours later, possibly a little longer,

sticking close to the cover, and with closed eyes,

concentrating my whole soul upon the task of

breathing in enough air to keep me going and at the

same time of avoiding breathing in enough water to

drown me, it seemed to me that I heard voices. The

rain had ceased, and wind and sea were easing

marvelously. Not twenty feet away from me, on

another hatch cover were Captain Oudouse and the

heathen. They were fighting over the possession of

the cover--at least, the Frenchman was. "Paien

noir!" I heard him scream, and at the same time I

saw him kick the kanaka.

Now, Captain Oudouse had lost all his

clothes, except his shoes, and they were heavy

brogans. It was a cruel blow, for it caught the

heathen on the mouth and the point of the chin, half

stunning him. I looked for him to retaliate, but he

contented himself with swimming about forlornly a

safe ten feet away. Whenever a fling of the sea

threw him closer, the Frenchman, hanging on with his

hands, kicked out at him with both feet. Also, at

the moment of delivering each kick, he called the

kanaka a black heathen.

"For two centimes I'd come over there

and drown you, you white beast!" I yelled.

The only reason I did not go was that

I felt too tired. The very thought of the effort to

swim over was nauseating. So I called to the kanaka

to come to me, and proceeded to share the hatch

cover with him. Otoo, he told me his name was

(pronounced o-to-o ); also, he told me that he was a

native of Bora Bora, the most westerly of the

Society Group. As I learned afterward, he had got

the hatch cover first, and, after some time,

encountering Captain Oudouse, had offered to share

it with him, and had been kicked off for his pains.

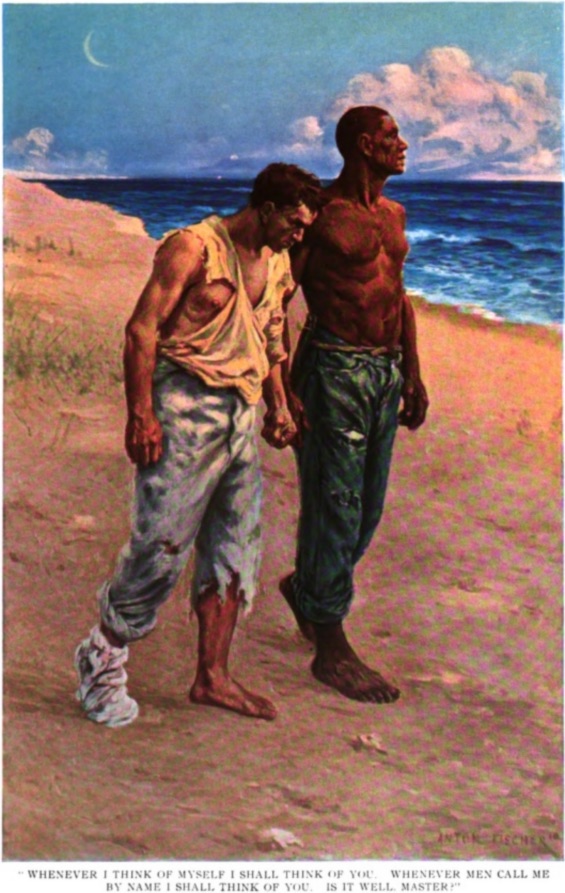

And that was how Otoo and I first

came together. He was no fighter. He was all

sweetness and gentleness, a love creature, though he

stood nearly six feet tall and was muscled like a

gladiator. He was no fighter, but he was also no

coward. He had the heart of a lion; and in the years

that followed I have seen him run risks that I would

never dream of taking. What I mean is that while he

was no fighter, and while he always avoided

precipitating a row, he never ran away from trouble

when it started. And it was "Ware shoal!" when once

Otoo went into action. I shall never forget what he

did to Bill King. It occurred in German Samoa. Bill

King was hailed the champion heavyweight of the

American Navy. He was a big brute of a man, a

veritable gorilla, one of those hard-hitting,

rough-housing chaps, and clever with his fists as

well. He picked the quarrel, and he kicked Otoo

twice and struck him once before Otoo felt it to be

necessary to fight. I don't think it lasted four

minutes, at the end of which time Bill King was the

unhappy possessor of four broken ribs, a broken

forearm, and a dislocated shoulder blade. Otoo knew

nothing of scientific boxing. He was merely a

manhandler; and Bill King was something like three

months in recovering from the bit of manhandling he

received that afternoon on Apia beach.

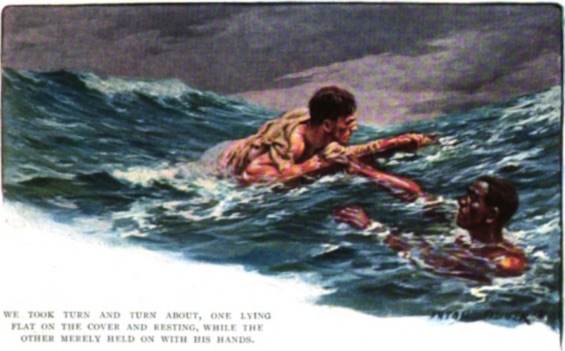

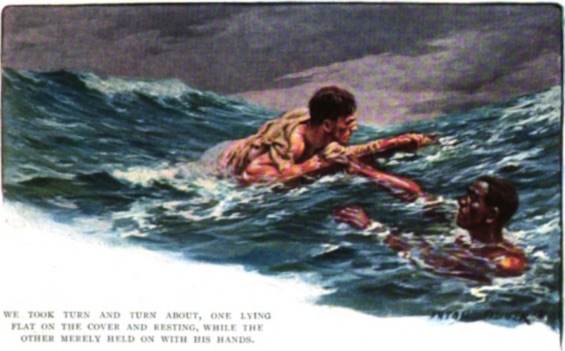

We took turn and turn about, one

lying flat on the cover and resting, while the

other,

We took turn and turn about, one

lying flat on the cover and resting, while the

other,

submerged to the neck, merely held on with his

hands.

In the end, Otoo saved my life; for I

came to lying on the beach twenty feet from the

water, sheltered from the sun by a couple of

cocoanut leaves. No one but Otoo could have dragged

me there and stuck up the leaves for shade. He was

lying beside me. I went off again; and the next time

I came round, it was cool and starry night, and Otoo

was pressing a drinking cocoanut to my lips.

We were the sole survivors of the

Petite Jeanne. Captain Oudouse must have succumbed

to exhaustion, for several days later his hatch

cover drifted ashore without him. Otoo and I lived

with the natives of the atoll for a week, when we

were rescued by the French cruiser and taken to

Tahiti. In the meantime, however, we had performed

the ceremony of exchanging names. In the South Seas

such a ceremony binds two men closer together than

blood brothership. The initiative had been mine; and

Otoo was rapturously delighted when I suggested it.

"It is well," he said, in Tahitian.

"For we have been mates together for two days on the

lips of Death."

"But death stuttered," I smiled.

"It was a brave deed you did,

master," he replied, "and Death was not vile enough

to speak."

"Why do you 'master' me?" I demanded,

with a show of hurt feelings. "We have exchanged

names. To you I am Otoo. To me you are Charley. And

between you and me, forever and forever, you shall

be Charley, and I shall be Otoo. It is the way of

the custom. And when we die, if it does happen that

we live again somewhere beyond the stars and the

sky, still shall you be Charley to me, and I Otoo to

you."

"Yes, master," he answered, his eyes

luminous and soft with joy.

"There you go!" I cried indignantly.

"What does it matter what my lips

utter?" he argued. "They are only my lips. But I

shall think Otoo always. Whenever I think of myself,

I shall think of you. Whenever men call me by name,

I shall think of you. And beyond the sky and beyond

the stars, always and forever, you shall be Otoo to

me. Is it well, master?"

I hid my smile, and answered that it

was well.

We parted at Papeete. I remained

ashore to recuperate; and he went on in a cutter to

his own island, Bora Bora. Six weeks later he was

back. I was surprised, for he had told me of his

wife, and said that he was returning to her, and

would give over sailing on far voyages.

"Where do you go, master?" he asked,

after our first greetings.

I shrugged my shoulders. It was a

hard question.

"All the world," was my answer--"all

the world, all the sea, and all the islands that are

in the sea."

"I will go with you," he said simply.

"My wife is dead."

I never had a brother; but from what

I have seen of other men's brothers, I doubt if any

man ever had a brother that was to him what Otoo was

to me. He was brother and father and mother as well.

And this I know: I lived a straighter and better man

because of Otoo. I cared little for other men, but I

had to live straight in Otoo's eyes. Because of him

I dared not tarnish myself. He made me his ideal,

compounding me, I fear, chiefly out of his own love

and worship and there were times when I stood close

to the steep pitch of hell, and would have taken the

plunge had not the thought of Otoo restrained me.

His pride in me entered into me, until it became one

of the major rules in my personal code to do nothing

that would diminish that pride of his.

Naturally, I did not learn right away

what his feelings were toward me. He never

criticized, never censured; and slowly the exalted

place I held in his eyes dawned upon me, and slowly

I grew to comprehend the hurt I could inflict upon

him by being anything less than my best.

For seventeen years we were together;

for seventeen years he was at my shoulder, watching

while I slept, nursing me through fever and

wounds--ay, and receiving wounds in fighting for me.

He signed on the same ships with me; and together we

ranged the Pacific from Hawaii to Sydney Head, and

from Torres Straits to the Galapagos. We blackbirded

from the New Hebrides and the Line Islands over to

the westward clear through the Louisades, New

Britain, New Ireland, and New Hanover. We were

wrecked three times--in the Gilberts, in the Santa

Cruz group, and in the Fijis. And we traded and

salved wherever a dollar promised in the way of

pearl and pearl shell, copra, beche-de-mer, hawkbill

turtle shell, and stranded wrecks.

It began in Papeete, immediately

after his announcement that he was going with me

over all the sea, and the islands in the midst

thereof. There was a club in those days in Papeete,

where the pearlers, traders, captains, and riffraff

of South Sea adventurers forgathered. The play ran

high, and the drink ran high; and I am very much

afraid that I kept later hours than were becoming or

proper. No matter what the hour was when I left the

club, there was Otoo waiting to see me safely home.

At first I smiled; next I chided him.

Then I told him flatly that I stood in need of no

wet-nursing. After that I did not see him when I

came out of the club. Quite by accident, a week or

so later, I discovered that he still saw me home,

lurking across the street among the shadows of the

mango trees. What could I do? I know what I did do.

Insensibly I began to keep better

hours. On wet and stormy nights, in the thick of the

folly and the fun, the thought would persist in

coming to me of Otoo keeping his dreary vigil under

the dripping mangoes. Truly, he made a better man of

me. Yet he was not strait-laced. And he knew nothing

of common Christian morality. All the people on Bora

Bora were Christians; but he was a heathen, the only

unbeliever on the island, a gross materialist, who

believed that when he died he was dead. He believed

merely in fair play and square dealing. Petty

meanness, in his code, was almost as serious as

wanton homicide; and I do believe that he respected

a murderer more than a man given to small practices.

Concerning me, personally, he

objected to my doing anything that was hurtful to

me. Gambling was all right. He was an ardent gambler

himself. But late hours, he explained, were bad for

one's health. He had seen men who did not take care

of themselves die of fever. He was no teetotaler,

and welcomed a stiff nip any time when it was wet

work in the boats. On the other hand, he believed in

liquor in moderation. He had seen many men killed or

disgraced by square-face or Scotch.

Otoo had my welfare always at heart.

He thought ahead for me, weighed my plans, and took

a greater interest in them than I did myself. At

first, when I was unaware of this interest of his in

my affairs, he had to divine my intentions, as, for

instance, at Papeete, when I contemplated going

partners with a knavish fellow-countryman on a guano

venture. I did not know he was a knave. Nor did any

white man in Papeete. Neither did Otoo know, but he

saw how thick we were getting, and found out for me,

and without my asking him. Native sailors from the

ends of the seas knock about on the beach in Tahiti;

and Otoo, suspicious merely, went among them till he

had gathered sufficient data to justify his

suspicions. Oh, it was a nice history, that of

Randolph Waters. I couldn't believe it when Otoo

first narrated it; but when I sheeted it home to

Waters he gave in without a murmur, and got away on

the first steamer to Aukland.

At first, I am free to confess, I

couldn't help resenting Otoo's poking his nose into

my business. But I knew that he was wholly

unselfish; and soon I had to acknowledge his wisdom

and discretion. He had his eyes open always to my

main chance, and he was both keen-sighted and

far-sighted. In time he became my counselor, until

he knew more of my business than I did myself. He

really had my interest at heart more than I did.

'mine was the magnificent carelessness of youth, for

I preferred romance to dollars, and adventure to a

comfortable billet with all night in. So it was well

that I had some one to look out for me. I know that

if it had not been for Otoo, I should not be here

today.

Of numerous instances, let me give

one. I had had some experience in blackbirding

before I went pearling in the Paumotus. Otoo and I

were on the beach in Samoa--we really were on the

beach and hard aground--when my chance came to go as

recruiter on a blackbird brig. Otoo signed on before

the mast; and for the next half-dozen years, in as

many ships, we knocked about the wildest portions of

Melanesia. Otoo saw to it that he always pulled

stroke-oar in my boat. Our custom in recruiting

labor was to land the recruiter on the beach. The

covering boat always lay on its oars several hundred

feet off shore, while the recruiter's boat, also

lying on its oars, kept afloat on the edge of the

beach. When I landed with my trade goods, leaving my

steering sweep apeak, Otoo left his stroke position

and came into the stern sheets, where a Winchester

lay ready to hand under a flap of canvas. The boat's

crew was also armed, the Sniders concealed under

canvas flaps that ran the length of the gunwales.

While I was busy arguing and

persuading the woolly-headed cannibals to come and

labor on the Queensland plantations Otoo kept watch.

And often and often his low voice warned me of

suspicious actions and impending treachery.

Sometimes it was the quick shot from his rifle,

knocking a nigger over, that was the first warning I

received. And in my rush to the boat his hand was

always there to jerk me flying aboard. Once, I

remember, on Santa Anna, the boat grounded just as

the trouble began. The covering boat was dashing to

our assistance, but the several score of savages

would have wiped us out before it arrived. Otoo took

a flying leap ashore, dug both hands into the trade

goods, and scattered tobacco, beads, tomahawks,

knives, and calicoes in all directions.

This was too much for the

woolly-heads. While they scrambled for the

treasures, the boat was shoved clear, and we were

aboard and forty feet away. And I got thirty

recruits off that very beach in the next four hours.

The particular instance I have in

mind was on Malaita, the most savage island in the

easterly Solomons. The natives had been remarkably

friendly; and how were we to know that the whole

village had been taking up a collection for over two

years with which to buy a white man's head? The

beggars are all head-hunters, and they especially

esteem a white man's head. The fellow who captured

the head would receive the whole collection. As I

say, they appeared very friendly; and on this day I

was fully a hundred yards down the beach from the

boat. Otoo had cautioned me; and, as usual when I

did not heed him, I came to grief.

The first I knew, a cloud of spears

sailed out of the mangrove swamp at me. At least a

dozen were sticking into me. I started to run, but

tripped over one that was fast in my calf, and went

down. The woolly-heads made a run for me, each with

a long-handled, fantail tomahawk with which to hack

off my head. They were so eager for the prize that

they got in one another's way. In the confusion, I

avoided several hacks by throwing myself right and

left on the sand.

Then Otoo arrived--Otoo the

manhandler. In some way he had got hold of a heavy

war club, and at close quarters it was a far more

efficient weapon than a rifle. He was right in the

thick of them, so that they could not spear him,

while their tomahawks seemed worse than useless. He

was fighting for me, and he was in a true Berserker

rage. The way he handled that club was amazing.

Their skulls squashed like overripe

oranges. It was not until he had driven them back,

picked me up in his arms, and started to run, that

he received his first wounds. He arrived in the boat

with four spear thrusts, got his Winchester, and

with it got a man for every shot. Then we pulled

aboard the schooner, and doctored up.

Seventeen years we were together. He

made me. I should today be a supercargo, a

recruiter, or a memory, if it had not been for him.

"You spend your money, and you go out

and get more," he said one day. "It is easy to get

money now. But when you get old, your money will be

spent, and you will not be able to go out and get

more. I know, master. I have studied the way of

white men. On the beaches are many old men who were

young once, and who could get money just like you.

Now they are old, and they have nothing, and they

wait about for the young men like you to come ashore

and buy drinks for them.

"The black boy is a slave on the

plantations. He gets twenty dollars a year. He works

hard. The overseer does not work hard.

He rides a horse and watches the

black boy work. He gets twelve hundred dollars a

year. I am a sailor on the schooner. I get fifteen

dollars a month. That is because I am a good sailor.

I work hard. The captain has a double awning, and

drinks beer out of long bottles. I have never seen

him haul a rope or pull an oar. He gets one hundred

and fifty dollars a month. I am a sailor. He is a

navigator. 'master, I think it would be very good

for you to know navigation."

Otoo spurred me on to it. He sailed

with me as second mate on my first schooner, and he

was far prouder of my command than I was myself.

Later on it was:

"The captain is well paid, master;

but the ship is in his keeping, and he is never free

from the burden. It is the owner who is better

paid--the owner who sits ashore with many servants

and turns his money over."

"True, but a schooner costs five

thousand dollars--an old schooner at that," I

objected. "I should be an old man before I saved

five thousand dollars."

"There be short ways for white men to

make money," he went on, pointing ashore at the

cocoanut-fringed beach.

We were in the Solomons at the time,

picking up a cargo of ivory nuts along the east

coast of Guadalcanar.

"Between this river mouth and the

next it is two miles," he said.

"The flat land runs far

back. It is worth nothing now. Next year--who

knows?--or the year after, men will pay much money

for that land. The anchorage is good. Big steamers

can lie close up. You can buy the land four miles

deep from the old chief for ten thousand sticks of

tobacco, ten bottles of square-face, and a Snider,

which will cost you, maybe, one hundred dollars.

Then you place the deed with the commissioner; and

the next year, or the year after, you sell and

become the owner of a ship."

I followed his lead, and his words

came true, though in three years, instead of two.

Next came the grasslands deal on Guadalcanar--twenty

thousand acres, on a governmental nine hundred and

ninety-nine years' lease at a nominal sum. I owned

the lease for precisely ninety days, when I sold it

to a company for half a fortune. Always it was Otoo

who looked ahead and saw the opportunity. He was

responsible for the salving of the Doncaster--bought

in at auction for a hundred pounds, and clearing

three thousand after every expense was paid. He led

me into the Savaii plantation and the cocoa venture

on Upolu.

We did not go seafaring so much as in

the old days. I was too well off. I married, and my

standard of living rose; but Otoo remained the same

old-time Otoo, moving about the house or trailing

through the office, his wooden pipe in his mouth, a

shilling undershirt on his back, and a four-shilling

lava-lava about his loins. I could not get him to

spend money. There was no way of repaying him except

with love, and God knows he got that in full measure

from all of us. The children worshipped him; and if

he had been spoilable, my wife would surely have

been his undoing.

The children! He really was the one

who showed them the way of their feet in the world

practical. He began by teaching them to walk. He sat

up with them when they were sick. One by one, when

they were scarcely toddlers, he took them down to

the lagoon, and made them into amphibians. He taught

them more than I ever knew of the habits of fish and

the ways of catching them. In the bush it was the

same thing. At seven, Tom knew more woodcraft than I

ever dreamed existed. At six, Mary went over the

Sliding Rock without a quiver, and I have seen

strong men balk at that feat. And when Frank had

just turned six he could bring up shillings from the

bottom in three fathoms.

"My people in Bora Bora do not like

heathen--they are all Christians; and I do not like

Bora Bora Christians," he said one day, when I, with

the idea of getting him to spend some of the money

that was rightfully his, had been trying to persuade

him to make a visit to his own island in one of our

schooners--a special voyage which I had hoped to

make a record breaker in the matter of prodigal

expense.

I say one of our schooners, though

legally at the time they belonged to me. I struggled

long with him to enter into partnership.

"We have been partners from the day

the Petite Jeanne went down," he said at last. "But

if your heart so wishes, then shall we become

partners by the law. I have no work to do, yet are

my expenses large. I drink and eat and smoke in

plenty--it costs much, I know. I do not pay for the

playing of billiards, for I play on your table; but

still the money goes. Fishing on the reef is only a

rich man's pleasure. It is shocking, the cost of

hooks and cotton line. Yes; it is necessary that we

be partners by the law. I need the money. I shall

get it from the head clerk in the office."

So the papers were made out and

recorded. A year later I was compelled to complain.

"Charley," said I, "you are a wicked

old fraud, a miserly skinflint, a miserable land

crab. Behold, your share for the year in all our

partnership has been thousands of dollars. The head

clerk has given me this paper. It says that in the

year you have drawn just eighty-seven dollars and

twenty cents."

"Is there any owing me?" he asked

anxiously.

"I tell you thousands and thousands,"

I answered.

His face brightened, as with an

immense relief.

"It is well," he said. "See that the

head clerk keeps good account of it. When I want it,

I shall want it, and there must not be a cent

missing.

"If there is,:" he added fiercely,

after a pause, "it must come out of the clerk's

wages."

And all the time, as I afterwards

learned, his will, drawn up by Carruthers, and

making me sole beneficiary, lay in the American

consul's safe.

But the end came, as the end must

come to all human associations.

It occurred in the Solomons, where

our wildest work had been done in the wild young

days, and where we were once more-- principally on a

holiday, incidentally to look after our holdings on

Florida Island and to look over the pearling

possibilities of the Mboli Pass. We were lying at

Savo, having run in to trade for curios.

Now, Savo is alive with sharks. The

custom of the woolly-heads of burying their dead in

the sea did not tend to discourage the sharks from

making the adjacent waters a hangout. It was my luck

to be coming aboard in a tiny, overloaded, native

canoe, when the thing capsized. There were four

woolly-heads and myself in it, or rather, hanging to

it. The schooner was a hundred yards away.

I was just hailing for a boat when

one of the woolly-heads began to scream. Holding on

to the end of the canoe, both he and that portion of

the canoe were dragged under several times. Then he

loosed his clutch and disappeared. A shark had got

him.

The three remaining niggers tried to

climb out of the water upon the bottom of the canoe.

I yelled and cursed and struck at the nearest with

my fist, but it was no use. They were in a blind

funk. The canoe could barely have supported one of

them. Under the three it upended and rolled

sidewise, throwing them back into the water.

I abandoned the canoe and started to

swim toward the schooner, expecting to be picked up

by the boat before I got there. One of the niggers

elected to come with me, and we swam along silently,

side by side, now and again putting our faces into

the water and peering about for sharks. The screams

of the man who stayed by the canoe informed us that

he was taken. I was peering into the water when I

saw a big shark pass directly beneath me. He was

fully sixteen feet in length. I saw the whole thing.

He got the woolly-head by the middle, and away he

went, the poor devil, head, shoulders, and arms out

of the water all the time, screeching in a

heart-rending way. He was carried along in this

fashion for several hundred feet, when he was

dragged beneath the surface.

I swam doggedly on, hoping that that

was the last unattached shark. But there was

another. Whether it was one that had attacked the

natives earlier, or whether it was one that had made

a good meal elsewhere, I do not know. At any rate,

he was not in such haste as the others. I could not

swim so rapidly now, for a large part of my effort

was devoted to keeping track of him. I was watching

him when he made his first attack. By good luck I

got both hands on his nose, and, though his momentum

nearly shoved me under, I managed to keep him off.

He veered clear, and began circling about again. A

second time I escaped him by the same manoeuvre. The

third rush was a miss on both sides. He sheered at

the moment my hands should have landed on his nose,

but his sandpaper hide (I had on a sleeveless

undershirt) scraped the skin off one arm from elbow

to shoulder.

By this time I was played out, and

gave up hope. The schooner was still two hundred

feet away. My face was in the water, and I was

watching him manoeuvre for another attempt, when I

saw a brown body pass between us. It was Otoo.

"Swim for the schooner, master!" he

said. And he spoke gayly, as though the affair was a

mere lark. "I know sharks. The shark is my brother."

I obeyed, swimming slowly on, while

Otoo swam about me, keeping always between me and

the shark, foiling his rushes and encouraging me.

"The davit tackle carried away, and

they are rigging the falls," he explained, a minute

or so later, and then went under to head off another

attack.

By the time the schooner was thirty

feet away I was about done for. I could scarcely

move. They were heaving lines at us from on board,

but they continually fell short. The shark, finding

that it was receiving no hurt, had become bolder.

Several times it nearly got me, but each time Otoo

was there just the moment before it was too late. Of

course, Otoo could have saved himself any time. But

he stuck by me.

"Good-by, Charley! I'm finished!" I

just managed to gasp.

I knew that the end had come, and

that the next moment I should throw up my hands and

go down.

But Otoo laughed in my face, saying:

"I will show you a new trick. I will

make that shark feel sick!"

He dropped in behind me, where the

shark was preparing to come at me.

"A little more to the left!" he next

called out. "There is a line there on the water. To

the left, master--to the left!"

I changed my course and struck out

blindly. I was by that time barely conscious. As my

hand closed on the line I heard an exclamation from

on board. I turned and looked. There was no sign of

Otoo. The next instant he broke surface. Both hands

were off at the wrist, the stumps spouting blood.

"Otoo!" he called softly. And I could

see in his gaze the love that thrilled in his voice.

Then, and then only, at the very last

of all our years, he called me by that name.

"Good-by, Otoo!" he called.

Then he was dragged under, and I was

hauled aboard, where I fainted in the captain's

arms.

And so passed Otoo, who saved me and

made me a man, and who saved me in the end. We met

in the maw of a hurricane, and parted in the maw of

a shark, with seventeen intervening years of

comradeship, the like of which I dare to assert has

never befallen two men, the one brown and the other

white. If Jehovah be from His high place watching

every sparrow fall, not least in His kingdom shall

be Otoo, the one heathen of Bora Bora.

|