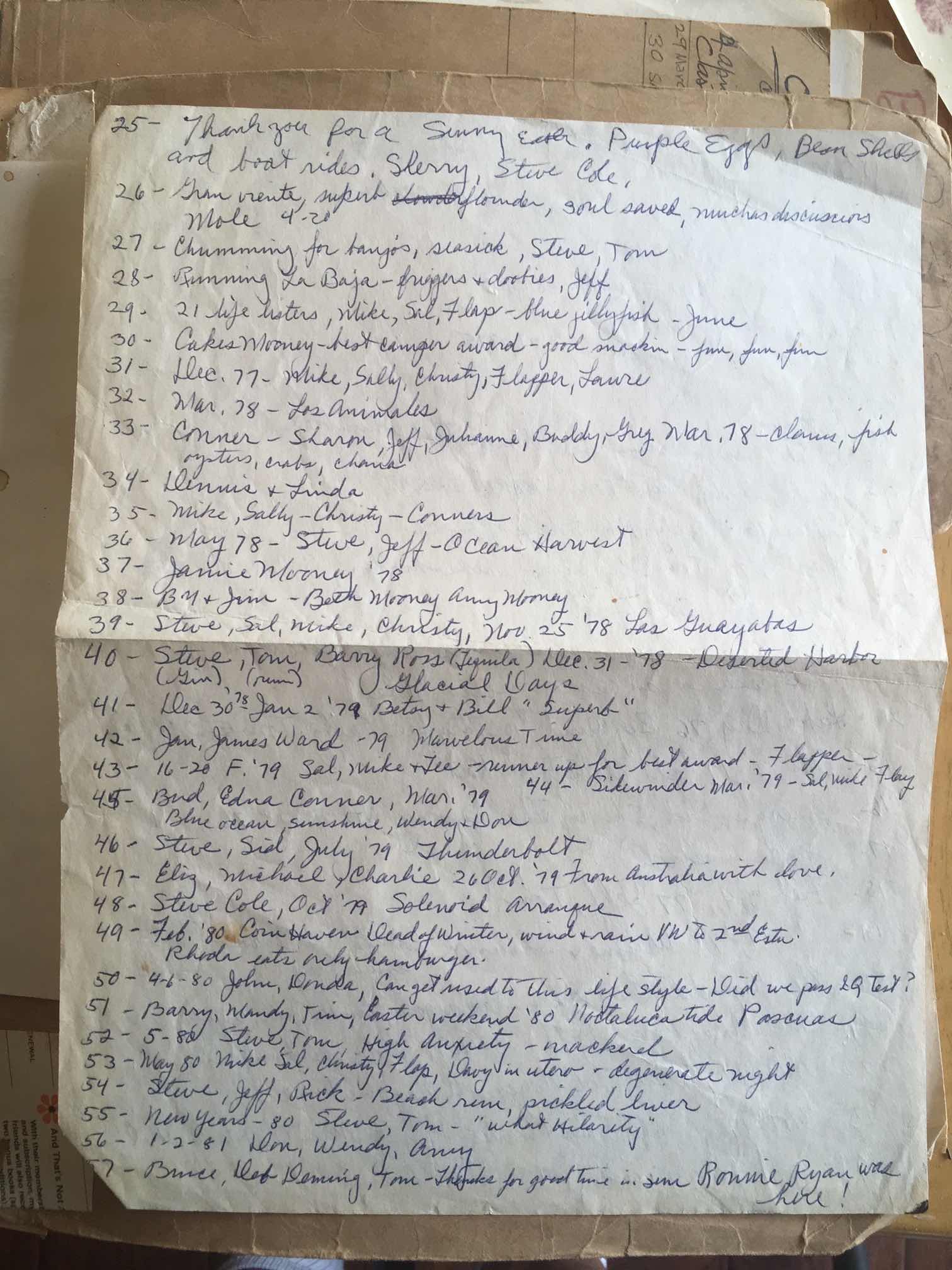

GREAT ESSAY ON ESTERO MORUA ADVENTURE

BY DAD OR MOM AND DAD

Most of it sounds like Dad's writing to me. However, I think

they were showing these essays to people together.

One February afternoon a squawking, crying medley of voices

attracted us to the beach in front of our house. We raced

toward the water where many hundreds of birds whirled,

soared, dived, clamored -- black, brown and white markings

contrasting with bright-colored beaks and legs. Here was

frantic activity directed at great schools of fish carried

in by the running tide. We watched the incredible number of

birds, each in its own manner, put on a show of fishing and

diving skill, a display that lasted over an hour. We counted

pelicans, terns, boobies, cormorants, grebes, gulls and

smaller birds until we gave up counting and just watched in

pure enjoyment. John Burroughs, writing about bird-watching,

commented "There is a fascination about it quite

overpowering." But after the fascination comes questions.

Where do all these birds nest?

Where do they fly each night to sleep? Which birds are true

residents and which are seasonal visitors -- or which are

just passing through? How and where do they find food when

the fishing is poor?

Like the people of the estuary,

only a handful of birds remain the year round. Most remain

for the winter season only, or visit briefly while en route

to summer or winter homes. Many, like the sandpipers, hatch

out near mountain streams in Alaska, on the shores of

Greenland, or in the tundra of Hudson Bay, and there they

will return to nest. Others stay with us all year --

homebodies like the Gambel's Quail, the Bigbilled Savannah

Sparrow, and Say's Phoebe, who nest beneath the dune shrubs

or in the eaves of beach porches. These, our daily

companions, are the birds we watch for at sunrise and

sunset. But the sea birds also beckon us daily to the

blue-green Gulf waters where the excitement of their

predatory life keeps us glued to binoculars for hours on

end.

The most striking and alluring of

these birds, the Pelicans and their many relatives such as

cormorants and boobies, are characterized by four-webbed

toes and throat pouches of varying colors, shapes and sizes.

e cart This order of birds, the peliformes, includes six

different families: 1) pelicans; 2) cormorants; 3) gannets

and boobies; 4) tropicbirds; 5) anhingas and darters; and 6)

frigate birds.

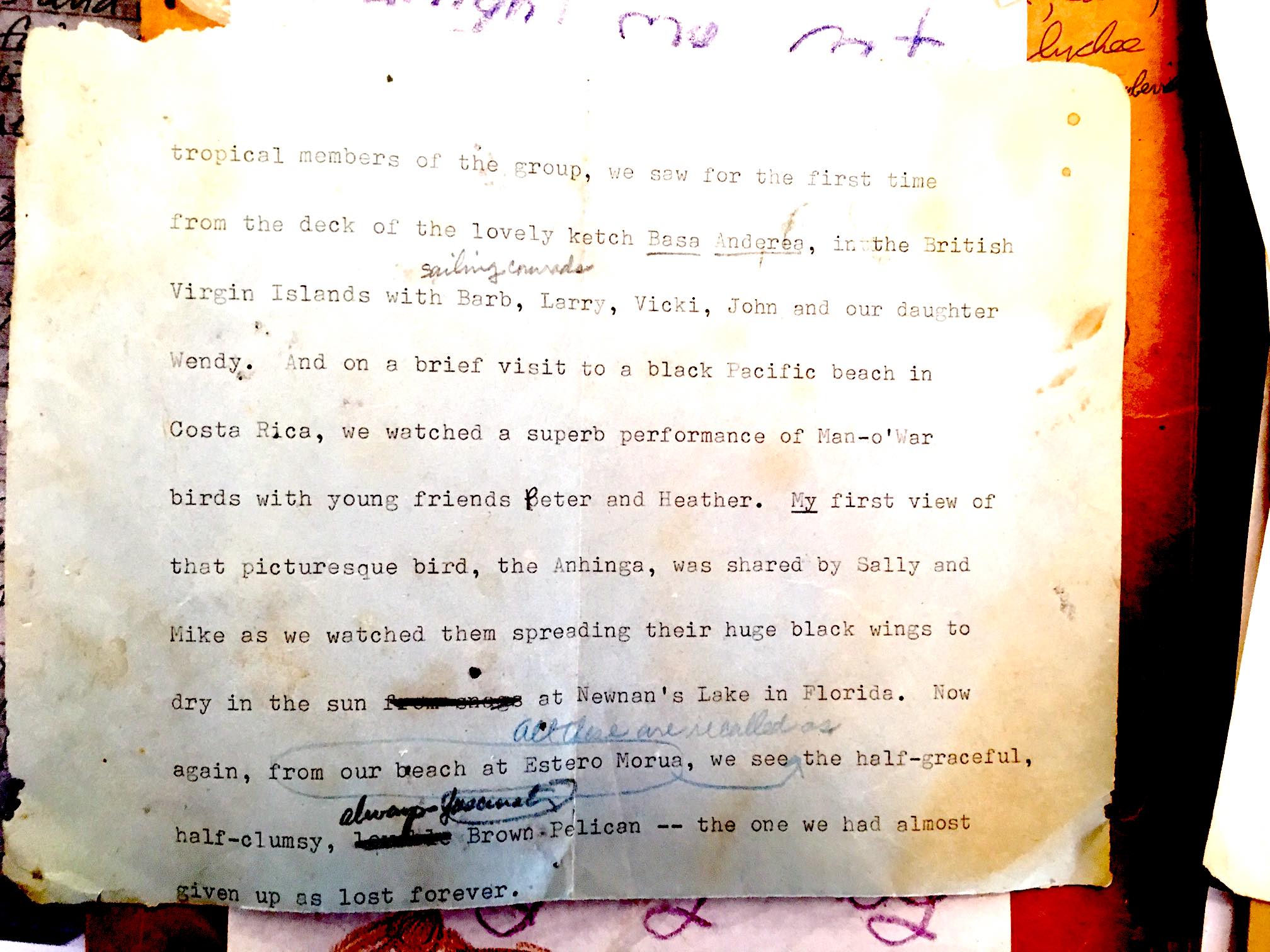

Our favorite of all these -- and

the one we almost gave up as lost forever -- is the Brown

Pelican, that half-clumsy, half-graceful, but always

fascinating sea bird. At one time we feared its extinction

with good reason. There were a few warnings in the 1950's

when the Brown Pelican's western population declined

somewhat. But by the turn of the 1960-70 decade both the

California and Baja populations seemed doomed. In 1969 and

1970 only 9 fledglings survived from 1,852 nests surveyed on

islands off the coast of southern California and

northwestern Baja. The cause, as we now know, was pollution

of their ocean environment by DDT-related discharges, mainly

from a Los Angeles manufacturer dumping liquid wastes into

the ocean. This resulted in disastrous eggshell thinning in

many species of birds including the Pelicans. Fortunately

for the Pelican ovyiat12, (and probably for fTian as well),

in 1970 the plant was forced to cease dumping its waste fnto

the ocean. It had been a close call for these large birds,

whose softened eggshells could not stand the weight of

parental care, and whose young were crushed to death before

hatching.

During this time on short winter

visits to the Gulf, we would scan the flocks with anxiety,

watching for those drab young-of-the-year among the

white-headed adults. Only seldom could we spot more than one

or two. Gradually they have come back, though not yet in

sufficient numbers for us to feel secure. Brown Pelican

productivity may still be too low for population stability

and we watch more carefully now, along with many others, for

aliim signs of environmental pollution.

But now, the pelicans are again

diving off-shore and sunning on the sand spit at low tide.

On today's walk to the estuary we witnessed a new sight.

Seventy pelicans were clustered on the near sand bar and, as

we watched, one after another threw back a head, stretched a

huge, yellow-orange throat pouch upward, beak skyward, and

turned the neck so the white plumage shone in the sun. The

head would then swing downward back to its normal position.

Each stretch seemed to call up a response from the others,

like a yawn, and one after another, sometimes three or four

together, would engage in this strange display, almost

flower-like in its colorful expansion. So far we have found

no reason for this unusual display.

Brown Pelicans, unlike their White

Pelican cousins, are skillful and adventurous divers. They

start at various altitudes, but always land with a foamy

splash; when they surface they are faced in the opposite

direction from which they entered the water. We haven't seen

any other diving birds making this sudden direction-switch

underwater. Their flying is amazingly agile and graceful for

birds of such bulk, and when they locate a school of fish,

they dip and turn in what seems to be ex-tremely close

quarters. We have yet to see them collide in mid-air as

gulls are apt to do when squabbling over a feast of fish.

Many other diving birds share the

fishing grounds and often a mixture of pelicans, boobies,

terns, cormorants and mergansers feed in a wild con-fusion

on a single large concentration of fish. Cormorants, the

next on eArk our peliform list, appear amidst the splashes

and below the aerial fishers. A Their dark heads, raised

above the water, appear at first glance to be loons, but

subsequent actions prove them otherwise. For one suddenly

rears up above the water, spreads his wings in a manner

similar to his relative the Anhinga, and immediately lifts

in flight, thus revealing himself a cormorant.

This black "cue_rvo marino" (as it

is called by the Mexicans), is often mistaken for a duck

because of its similar flight silhouette. At this time of

year there are many, forming long, dark lines against the

pale sky. Unspectacular compared to the diving birds, they

are neverthe-less such efficient fishers that they have long

been put to work for this purpose by the Chinese. Placing a

ring around the cormorant's neck to forestall swallowing,

the Chinese owner allows the tethered bird to fish, the

catch then being collected from the bird's pouch by this

enterprising human exploiter. Here, however, the cormorants

swim freely beneath the furious aerial activity and enjoy

the fruits of their own underwater fishing skill. e cl.a"

Gannets and boobies make up the

third of our peliform es list. The gannets we do not see

here -- they remain close to their northern rock clifti. But

we are fortunate to have the most beautiful of the Gulf

divers, the Brown Booby, perform for us. This spectacular

bird drops from both low and high altitudes, folding his

wings so tightly at the last minute of his flight that he

cleaves the water like an arrow. As he rises with his catch,

his sharp wings cut a clean line against the cloudless sky,

the brown and white pattern on his underside flashing in the

sun. One February day we spotted a few white-rumped

individuals among them, a feature of a different species,

the Blue-Footed Booby. Following them carefully with

glasses, we easily detected the blue beaks, but rarely could

catch the lovely blue color of the legs.

Another fascinating performance

that the Pelicans, Boobies and Terns have in common is a

"traffic circle" behavior. When a large school of fish

become the target, these divers follow a striking pattern.

They approach upwind, dive, soar upward, then circle

downwind and fall in, more or less near the end of the

group, again approaching upwind until each bird in the group

peels off when it it time to strike again. From a distance

it looks much like a busy "traffic pattern" at some modern

airport, even to the upwind approach.

Cousin to the pelicans and boobies,

the Red-Billed Tropicbird, is seldom seen close to shore. We

were fortunate to encounter one on a boat trip from our own

Puerto Penasco to Bird Island, a group of rocky peaks six

miles off shore and south of us in the Gulf. Traveling by

motorboat, mainly to fish and to view the sea lions and

porpoises, we were honored by a half hour visit by this

amazing bird who chose to playfully criss-cross our boat,

hanging about 15 feet above our heads, speeding up as we

did, racing us in the spirit of game-playing -- and proving

our boat was no match for his speed:

The anhingas and darters are not

seen in the Gulf, but occasionally we are visited by the

Magnificent Frigatebird. Once at Thanksgiving we saw several

flying along the beach.

The other diving birds in this

fishing assemblage are the terns, their specific composition

varying with the season. Today, the first of February,

hundreds of Forster's Terns have suddenly appeared over the

shallow shore. We have seen but a few before today. In their

hungry diving for shiners they are almost frenetic, their

continuous calls making a noisy, collective chatter. From

past years' experiences, we know that one morning we'll hear

a new note, a voice of Spring -- a screaming from high

above. There, streaking across the bright sky in close

formation, a pair of prosaically-named "common" Terns will

be seen cutting a sharp outline against the blue. Some will

stay for a few weeks to wheel and dive with the Forster's

Terns, adding a familiar Cape Cod dimension to the sound

medley arising from the beach surf. These, the birds Thoreau

called "Mackerel Gulls", are welcome visitors during March

and April, and then one day they are gone -- on their way to

island homes far north, perhaps to New England's coast, or

Canadian lakes.

Other terns appear, each with a

special appeal. The Elegant Tern is one of these; few

American bird watchers have seen this species although it

occasionally wanders to the coast of southern California

from its breeding grounds on islands in the Gulf. The Least

Tern, bouncing above the estuary waters in summer is a

favorite, perhaps because it's so easy to identify: its call

is swallow-like, and its yellow bill is a diagnostic delight

for the amateur. We are always on the lookout for the large

Caspian and Royal Terns; they are oddities, seeming to

lumber across the water in gull-like flight compared to

their buoyant smaller cousins. But, the most incongruous of

the group are the Black Terns, who feed here briefly in May

before leaving for in-land domesticity in Canada and

northern USA, far from marine shores. Each day during our

walks we make discoveries on the beach. Some are unpleasant,

underscoring the damage man inflicts on his fellow

creatures, often unwittingly. Today we found, at high water

mark, a dead blue-footed booby; on closer examination, the

cause of death became unhappily clear. Wound tightly around

one foot and one wing was a nylon monofilament fishing line,

one of man's lethal snares for un-suspecting wildlife. How

he had become entangled will never be known, but his death

was surely one of hopeless struggle. The finding recalled a

similar incident that occurred a few years back on Convict

Lake in California. This was a strange event, yet with a

much happier ending than today's sad find.

We had been camping at Hot Springs

Creek, but decided to visit Convict Lake because of its

reputation as an extremely beautiful and limnologic site,

and indeed it was. In fact, it was so delightful that we

decided to walk around it. As we were returning, having

nearly com-pleted the long loop, we noticed a California

gull sitting in a shallow bay, strangely motionless. Turning

glasses on the bird, we could also see a good-sized trout

close beside it. This seemed most unusual and we walked back

toward the bird who made no motion to fly. Wading into the

water toward him we discovered he had become entangled in

cfishing line -- a line to which the fish was securely

hooked.

We had with us no equipment

whatever, but by wading closer, Jerry was able to divert the

bird with one hand and grab him securely with the other.

Then, with Jerry holding him aloft -- fish, fishing line and

all -- I was ten-able to grab his feet, both of which were

tightly entangled in the line. I used the only weapon at

hand, my teeth, and broke the line in two places so I could

then unravel it and free the bird's feet. I still recall,

vividly, biting the tough line with my fac-e

-haTiburtiect—irt the -soft, white gull feather face

half-buried in the soft, white gull feathers. Once

untangled, the bird was placed back in the water and after a

few minutes of paddling his feet, he flew out toward the

middle of the lake, where he landed --either to rest or to

sooth his sore feet in the water. The sight was well worth

our entire day's visit. The fish and line we buried so no

other bird would become entangled.

After the adventure at Convict

Lake, we have looked on all gulls with affection, although

most people do not count them among their avian favorites.

The gulls evoke mixed emotions -- master fliers, they

sur-pass the most graceful] glissade, but their mores can be

questioned from an anthropocentric viewpoint. Gluttony,

thievery, murder and cannibalism all have been part of their

heritage, and these traits must have had substantial

survival value in the long history of this species. Whatever

their personality, they are part of the seasonal panorama at

the estuary, and they are as welcome as the gentler species.

Gull-watching involves spotting

beak colors, leg hues, and wing tip/mantle comparisons. The

Ring-Billed Gull is a winter resident along with the

similar, but larger and ubiquitous Herring Gull. It is the

former, however, that is our "haus Vogel", visiting us daily

for scraps and perching on nearby porch railings. The

Herring Gull, with the coldest of eyes, seems to disdain

such handouts. When we drive to Puerto Penasco, however, we

find him abundantly in the smelly dump, belying his dignity

and independence. If we happen to approach downwind, the

entire flock takes off directly toward us, swerving off to

safety the moment they are airborne. Most of these

scavengers are Herring Gulls.

In some ways the herring gull is

not such a fine bird. We knew he was a scavenger, but we did

not realize he was a bird-killer until one day, through bird

glasses, we saw three herring gulls nipping at an eared

grebe. The grebe seemed to be trapped in a very shallow

back-water quite a distance from the receding tide. He was

making valiant efforts to achieve that distance by flapping

along against a powerful wind and sinking back into the

water, too shallow for him to dive away from the gulls.

Twice while we watched a gull lifted him a foot aloft, only

to drop him when he struggled. The grebe seemed additionally

inhibited by the fact that he had been moulting and could

not get under-way against the strong wind. We broke all

sprint records in our dash to drive away the gulls, and

walked guard for the grebe until he was able to achieve the

'ocean edge and deep-water safety. He seemed not seriously

hurt, but we chalked up one more answer to why so many dead

grebes had been seen on the beach.

In Spring, the dainty Bonaparte's

Gulls join the beach crown. More tern-like than the others,

they prefer to sit on sandbars among the terns rather than

with their closer relatives. Later, during the summer

months, a few Western and California Gulls move in to

replace the Herring and Ring-Billed Bulls who have moved to

their nesting places far to the north. The Western, with his

dark back, reminds us of the fierce Great Black-Backed Gull

who is part of the rugged scenery of Mount Desert Island and

the granite seascape of the Maine coast.

The best fisherman of the gull lot

is the darkest of them all, Heerman's Gull, and he is with

us all year. Except for their bright red beaks and white

heads, they blend in with the black lava boulders upon which

they perch along the waterfront at Puerto Penasco. Here at

the beach, whenever there is a fish-bird boil, with all the

pelicani-form species, grebes and mergansers diving and

surfacing frantically, the dark silouhettes of Heerman's

Gulls are part of the tableau. Usually one or two attend a

pelican, following his every aerial maneu-ver and slanting

down with his dive, alighting close to the spot where the

large fisherman surfaces with his catch. In the British

Virgin Islands we once watched the Laughing Gulls attend

Brown Pelicans in the same manner, sitting close by

individuals that had just dived, emerged and were floating

on the bluest of Caribbean waters. This behavior on the part

of the gulls must have some advantage; perhaps the pelican

is a sloppy eater, dropping tidbits or more likely losing a

newly-caught fish. If so, the other gulls at Estero Morua

haven't learned it yet, and are missing a good thing.

Sometimes, though seldom, the

Osprey joins this diversified group of fishermen. Usually a

solitary hunter, the Osprey uses a different approach.

Hovering over his prey until the fish is close to the

surface, he then dives, plucking his catch out of the sea

with his powerful talons and carrying it to a shore perch to

enjoy at leisure. Each morning when we step out of the door

onto the warm sand we look east-ward to seekuaf our resident

"fish-hawk" is perched on his pole behind an empty beach

house. We have been watching him foraging both in the

estuary and offshore, and recognize him by the short fish

line dragging from his leg. So far, it seems to have not

affected his fishing, but we are concerned that sometime it

may tangle him up with fatal results.

There is a legend, or perhaps it

should be called a myth, that concerns these estuary

Ospreys. It may exist elsewhere, but we had not heard it

before. In several places at Estero Morua, near the beach or

high on a dune, stand slender, tall poles, each usually

topped with a curved boat hook and with a braced crossbar.

They were raised in memory of deceased friends or loved ones

in hopes that the "sea eagle" would use them as perches.

Each time the hawk returns to the pole, the tradition goes,

the soul of the departed returns with him to relive joyful

times spent here. To those who credit such fantasies of

rein-carnation, it is especially pleasurable to see the

Osprey land on one of the lofty perches. It is a reminder of

those who enjoyed the estuary before us, even though we

don't know to which individual soul each pole belongs.

Indeed, it is such a delightful myth that we hope to be so

honored by someone who lives here after us, so we can fly

back with the Osprey for brief visits.

Sometimes the poles are used by

other birds, usually as a sally point. The graceful little

American Kestrel is often perched high on a bar meant for

Ospreys, and he seems nearly acceptable as a spirit bearer.

The occasional shrike and Say's Phoebe do not make quite as

good substitutes for a sea eagle, but there was no question

-- no doubt whatsoever -- that the two Starlings we saw one

time high up on the dune pole, represented the reincarnation

of no one we wanted to know! (A son-in-law, reading the

foregoing statement, called it "continental chauvinism".)

On a sunny, windy day in February

we walked over the dunes to the estuary, not to catch fish,

crabs or oysters, but simply to bird-watch. The tide was at

the ebb with only a shallow stream making its last hurried

exit to the Gulf. But beyond the fast-flowing rivulet, in a

shallow backwater curved up against a dune, floated fifteen

ducks, paddling back and forth lazily. A familiar green

flash announced an old friend, the GreeTinged Teal. It was

the first time we had seen the species in the Gulf and we

watched their activity for nearly an hour. The green was not

obvious at first, but as one after another would rise up on

the water, flapping his wings, a white chest and under-wing

appeared; then, as they settled back onto the smooth water,

a bright jade, almost irridescent in its brilliance, would

flash briefly before the wings again folded, leaving only

slight tips of emerald still showing. By looking closely we

could make out the green eye patch on the males -- the same

lovely bright shade, but muted by the rich dark cinnamon

feathers that surrounded it.

Much more common than the teal and

the most abundant of our ducks are the wintering

Red-Breasted Mergansers. Returning from our walk that day,

we came upon a handsome male, all alone near the reefs; he

seemed undisturbed by our presence. Usually the Gulf

mergansers are gregarious, gathering in great rafts to fish,

but this one seemed to be making a solitary toilet. He was

close enough for us to admire his markings even without

glasses, but with them, every colorful detail of his

plumage, his bright red beak and eye, his red-brown and

speckled breast and white neck band, could be enjoyed at

very close view as he preened and bathed. Excellent

fishermen, these ducks have sharply serrated beaks,and any

fish they seize has little chance of slipping away. Modern

birds have no true teeth, but the notched bills of the

mergansers serve them effectively, pseudo-teeth though they

may be. Cinnamon Teal occasionally visit here and twice,

while we were hunting oysters on the outer reef, a small

dark goose, the Black Brant, went honking past us hardly

higher than our heads. This was an unusual occurnce, as we

see very few such geese. By contrast, the Surf Scoter is a

regular winter visitor. We have found several dead on the

beach and we always speculate on the cause while admiring

the bright red and white beak, much more colorful than shown

in our guide book. A round, black spot centered in the white

base of the bill gives the appearance of a large eye,

bringing to mind the deceptive "eye" near the tail on many

of the brilliant fish we have seen on tropical reefs. The

Surf Scoter's real eye is small, set farther back and nearly

hidden beneath the white marking on the forehead.

Two other elegant, graceful and

familiar birds, the Great Blue Heron and the Snowy Egret,

frequent the estuary and the off-shore reefs These birds

exhibit distinct differences in their feeding habits; the

Egret is a busy hunter, cruising back and forth through the

shallows, constantly on the move; the larger Great Blue

Heron stands motionless, tensely poised, waiting for long

moments before a lightning-fast strike secures his prey.

Both are strikingly beautiful to watch, but nothing can

equal the flowing ease of the Great Blue Heron as he slows

to land, daintily setting his feet onto the sand, his lovely

slate-blue wings gleaming a moment in the sun before he

folds their color into the familiar grey-blue profile.

In the Gulf the loneliness of the

Great Blue Heron contrasts sharply with their behavior in

their nesting habitat. Lake Itasca, Minnesota, was one of

these places where three or four herons could usually be

spotted along the shoreline. During a summer stay at that

lake, we discovered a busy rookery in a nearby grove of red

pines where dozens of pairs resided. Although they ranged

far to supply their nestlings, some always were hunting the

Itasca shores. A unique feature of these Minnesota herons

was their habit of landing on the water to float like

long-necked ducks. Our boys were young then and when fishing

from canoe or boat, they would throw unwanted perch high in

the air whenever the herons passed. This would bring the

great birds down to float buoy-antly while picking up the

fish. Then with one stroke of their wings they were airborne

and gaining altitude as they flew home to the rookery. This

was decidedly different behavior than the herons we watched

in the estuary.

Equally at home floating in the

estuary or fishing in a rough sea, the Eared Grebe is a

winter and spring visitor. We have come upon these

unsophisticated little divers foraging in the tide pools,

aware of our presence but showing no fear, apparently

unaware of the dangers associated with mankind. By mid March

their delicate golden "ears" (plain and unadorned in the

winter months), presage spring and the onset of warm

weather. The golden feathers, fluffing out in the spring

breeze on each side of the grebe's small head, reflect the

sun, and one instantly knows why they are called "eared"

grebes. Though strictly western birds, this year one

surprised the experts by turning up in a Christmas bird

count from the New York side of Lake Champlain -- an

unprecedented appearance. The American Oyster Catcher, a

louder, brighter, estuary inhabitant, is usually seen

whenever we walk to the oyster reefs to pry off the tilt,

delicious rock oysters for an evening meal. These birds

herald their approach with shrill, short cries, and they

continue to shriek as they pass, their red beaks bright and

distinctive. They seldom mingle with other species but stay

aloof in groups of two or, rarely, three. We see evidence of

their feeding at low tide; since many freshly-opened and

cleanly-picked shells remain to bleach in the sun, we assume

the birds are eating well.

The Turnstones, both Ruddy and

Black, also find much to their liking in and around the

oyster beds. Their characteristic foraging behavior of

flipping stones to search for invertebrate tidbits is fun to

watch. One day we chanced upon one of these birds who had an

un-welcome hunting companion -- a fast-moving sanderling.

The sanderling stood close by waiting until the turnstone

tossed aside a small stone; then he rushed in searching for

whatever prey might be uncovered; this seemed to confuse the

busy turnstone. Apparently that bird, at least, had not

experienced this type of looting before. More often,

sanderlings are found in small flocks on the beach, alone or

in company with a variety of other species, relying on no

one else for their dinner; with shallow probes, too rapid to

count, they seem to be sucking up nourish-ment unavailable

to other shore birds. We have never witnessed another

incident of a sanderling relying upon the skills of a

turnstone for his food.

All the shore feeders have a place

and a time to hunt and, thanks to the pull of sun and moon,

the tidal regime/offers varied opportunities. The sandpipers

skitter along in the shallows or wade deeper according to

species. The plovers, on the other hand, seem to be almost

afraid to wet their feet. The largest and most common plover

on our beach is the Black-Bellied Plover whose hunting

tactics remind one of a robin on a suburban lawn -- it runs

a few steps, stops, seems to listen, and suddenly plunges

its beak into the burrow of an unfor-tunate sandworm.

Recently a graduate student at Yale, armed with stopwatch

and notebook, showed that the steps between successive

plover probes mean something: if the bird has good luck, he

takes fewer steps before trying again. The Black-Bellied

Plover knows in some ancestral, selected-for behavioral way

that "clumping" is a common pattern of distribution among

animals, including his prey.

Other smaller plovers are less

common here. The Semipalmated Plover, striped like a little

Killdeer, seems to be a successful and widespread bird,

co-occurring with the others on our beaches. It is found on

the East Coast also, and on the sands of Cape Co it coexists

with the noisy Piping Plover, a counterpart of our western

Snowy Plover. The middle-sized Wilson's Plover isn't part of

the assemblage of other shorebirds on the beaches. Far less

sociable than other plovers, one or two occasionally visit

the tidal mud flats in the estuary. These birds display a

different pace from their relatives. Almost cat-like, they

stalk their prey; creeping closer and closer with head

lowered, they conclude with a last-minute dash for the

quarry. With such a foraging technique, they can ill afford

to hunt where other beach combers, running here and there,

might alarm their victim. Commonest of all the estuary

sandpipers, the Willet is also one of the most nondescript,

drab and undistinguished of shorebirds when seen feeding in

the shallow wake of receding tides. But he exemplifies

perfectly what Henry Beston meant when he wrote, "No one

really knows a bird until he has seen it in flight." With

its singularly striking black and white pattern, the airborn

Willet is a joy to watch. Once seen in flight, it can't be

forgotten.

In addition to distinctive beak

shape, leg color and flight pattern, a sandpiper can be

identified by its mode of feeding. If you see a lone bird

unhurriedly probing the mud flats high above the receding

tide, you may guess it's a Long-Billed Curlew. The sure

identification, of course, is the Curlew's long, curved beak

-- which contrasts to the straighter, shorter beak of the

Marbled Godwit -- a bird more apt to wade out from the

water's edge as the tide rises. The Willet's feeding pattern

is apt to fall somewhere in between these two. The Greater

Yellowlegs, on the other hand, lurches and splashes in a

drunken manner, chasing and seizing the prey it scares up. A

bird that runs along the water's edge at high tide, probing

rapidly in what appears to be sterile sand, is usually the

Sanderling, the largest of the "sand peeps".

Parenthetically, it seems wrong that the turnstones have the

generic name, Arenaria; it obviously belongs to the

Sanderling.

The Dunlin, Knot, Dowitcher,

Surfbird, Wandering Tattler, and the two smallest peeps, the

Western and Least Sandpipers -- all display a confusing

array of somber hues, but each is beautiful in his own way,

occupying his own niche in the beach economy.

In their distinctive, indivival

ways of living the sandpipers remind us of human behavior.

In this we again agree with Beston who called his outer Cape

sandpipers, "...the thin-footed, light-winged "peoples" ...

the busy pickup, runabout, and scurry-along "folk". The

peeps, in particular, remind one of a little person running

on the beach, now pausing to scan the field, then suddenly

changing his mind and racing for the ocean at full speed.

"Life no longer than a sand peep's

cry...", wrote Edna St. Vincent Millay, lamenting her years

spent away from the Maine coast. And we are reminded again,

how brief are the moments we are able to spend on the beach,

close to the ocean with our bird relatives who share this

planet.

|